The authors are with Cumberland Valley Analytical Services, Inc., Hagerstown, Md., and Paradox Nutrition, LLC, West Chazy, N.Y.

A major goal of corn silage making is to reduce oxygen and raise acidity rapidly so that lactic acid bacteria grow to stabilize and preserve or "pickle" the silage. Often, people believe that corn silage is fairly well fermented after three weeks in the silo or bag, and it is okay to start feeding it.

We analyzed 19,185 corn silage samples that were submitted to Cumberland Valley Analytical Services, Inc., from farms in New York between January 2004 and February 2008. All samples were analyzed using the near-infrared (NIR) technique. They ranged from 25 to 45 percent dry matter.

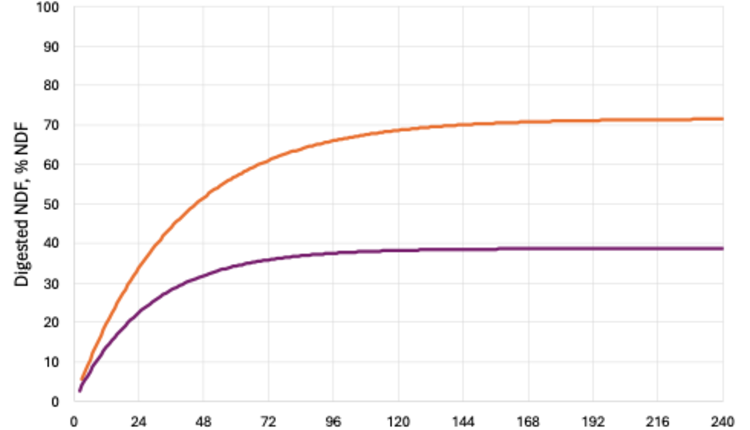

We looked at how the fermentation profiles, nutrient parameters, and starch digestibility (see graph) varied according to the month of the year that the samples were sent to the lab. We assumed month of sample submittal related to length of crop fermentation. We figured that all samples started their fermentation process sometime between August and October.

Corn silage that is ensiled properly has a rapid pH drop where lactic acid-producing bacteria predominate. Lactic acid should be a significant end-product of good corn silage fermentations. Higher levels of lactic acid indicate that the corn silage is stable.

Experts have found that well-preserved corn silage generally contains more than 3 percent lactic acid and less than 3 percent acetic acid with pH less than 4.0. Higher pH levels mean less acidity. Titratable acidity accounts for the strength of acids present in the corn silage and is highly correlated with total acid levels in corn silage.

In our study, lactic acid, pH, and titratable acidity did not reach maximum levels until four months after ensiling. Acetic acid levels continued to go up until six months after ensiling; pH was significantly higher in September, October, November, and even December.

Although we don't want extensive protein degradation in our corn silages, the level of ammonia and the level of soluble protein will continue to go up until the fermentation has stabilized. Soluble crude protein was lower during the first three months after ensiling and reached a plateau after four months. Ammonia was lower during the first six months after ensiling. Soluble protein and ammonia may be related to starch degradability.

With today's high grain prices, it has become even more important than ever to get our best use of corn silage and top milk production at all times.

Time after ensiling of corn silage may be important to consider for diet formulation.

You may need to make diet adaptations such as reducing starch levels when starch digestibility increases in order to prevent acidosis. When corn silage starch is less available, higher amounts of supplemental dietary starch may be needed to provide energy for the rumen microbes and the cow.

Researchers in the Netherlands sampled 15 corn silages from a variety of farms twice a month up to 10 months after ensiling. They found that three-hour in situ starch digestibility improved with storage time and was correlated with corn silage dry matter content at ensiling.

Average three-hour in situ starch digestibility was 53.2 percent and 69 percent at two months and 10 months after ensiling, respectively. Crude protein degradation went up with time of ensiling but was not correlated with starch digestion.

In our study, corn silage samples were analyzed for available starch by the NIR technique. We defined starch availability as the amount of starch degraded by a one-hour enzyme treatment. Available starch was lower in samples received in October, November, and December.

Most nutritionists and producers would agree that cows milk best on fully fermented corn silage. Our data indicate that most corn silage will not be fully fermented until it has ensiled for about four months. You should make ration adjustments to account for changes in corn silage nutrient content and digestibility that occur during time of ensiling and through the fermentation cycle.

Click here to return to the Crops & Forages E-Sources

090825_532

A major goal of corn silage making is to reduce oxygen and raise acidity rapidly so that lactic acid bacteria grow to stabilize and preserve or "pickle" the silage. Often, people believe that corn silage is fairly well fermented after three weeks in the silo or bag, and it is okay to start feeding it.

We analyzed 19,185 corn silage samples that were submitted to Cumberland Valley Analytical Services, Inc., from farms in New York between January 2004 and February 2008. All samples were analyzed using the near-infrared (NIR) technique. They ranged from 25 to 45 percent dry matter.

We looked at how the fermentation profiles, nutrient parameters, and starch digestibility (see graph) varied according to the month of the year that the samples were sent to the lab. We assumed month of sample submittal related to length of crop fermentation. We figured that all samples started their fermentation process sometime between August and October.

Corn silage that is ensiled properly has a rapid pH drop where lactic acid-producing bacteria predominate. Lactic acid should be a significant end-product of good corn silage fermentations. Higher levels of lactic acid indicate that the corn silage is stable.

Experts have found that well-preserved corn silage generally contains more than 3 percent lactic acid and less than 3 percent acetic acid with pH less than 4.0. Higher pH levels mean less acidity. Titratable acidity accounts for the strength of acids present in the corn silage and is highly correlated with total acid levels in corn silage.

In our study, lactic acid, pH, and titratable acidity did not reach maximum levels until four months after ensiling. Acetic acid levels continued to go up until six months after ensiling; pH was significantly higher in September, October, November, and even December.

Although we don't want extensive protein degradation in our corn silages, the level of ammonia and the level of soluble protein will continue to go up until the fermentation has stabilized. Soluble crude protein was lower during the first three months after ensiling and reached a plateau after four months. Ammonia was lower during the first six months after ensiling. Soluble protein and ammonia may be related to starch degradability.

With today's high grain prices, it has become even more important than ever to get our best use of corn silage and top milk production at all times.

Time after ensiling of corn silage may be important to consider for diet formulation.

You may need to make diet adaptations such as reducing starch levels when starch digestibility increases in order to prevent acidosis. When corn silage starch is less available, higher amounts of supplemental dietary starch may be needed to provide energy for the rumen microbes and the cow.

Researchers in the Netherlands sampled 15 corn silages from a variety of farms twice a month up to 10 months after ensiling. They found that three-hour in situ starch digestibility improved with storage time and was correlated with corn silage dry matter content at ensiling.

Average three-hour in situ starch digestibility was 53.2 percent and 69 percent at two months and 10 months after ensiling, respectively. Crude protein degradation went up with time of ensiling but was not correlated with starch digestion.

In our study, corn silage samples were analyzed for available starch by the NIR technique. We defined starch availability as the amount of starch degraded by a one-hour enzyme treatment. Available starch was lower in samples received in October, November, and December.

Most nutritionists and producers would agree that cows milk best on fully fermented corn silage. Our data indicate that most corn silage will not be fully fermented until it has ensiled for about four months. You should make ration adjustments to account for changes in corn silage nutrient content and digestibility that occur during time of ensiling and through the fermentation cycle.

090825_532