The information below has been supplied by dairy marketers and other industry organizations. It has not been edited, verified or endorsed by Hoard’s Dairyman.

When news broke this week of farmers being dropped from Grassland Dairy, it stirred within me a sadness for the farmers affected and frustration at the markets but also memories of the life I’d hoped to lead.

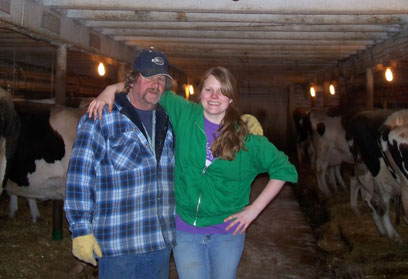

From the time I was a young girl, trailing Dad out to the barn to feed calves, I remember boldly declaring my plans for my future: “I’m going to be a farmer, too!”

My world revolved around our Chippewa County dairy farm. I woke early to help Dad with morning chores and headed straight back to the barn when the school bus dropped me off after school. Some of my best memories were those chore times spent with Dad, ambling along beneath the whitewashed barn beams. Through the big, weathered door on the end of the barnwalk, we watched the sun rise and dreamed of the future when I might raise my own family and herd at our Split Ridge Dairy.

So it was with angry, tear-filled eyes that I listened the day Dad told me he didn’t want me to follow in his footsteps. I was 17 years old.

We were in the milkhouse, waiting for the milkers to finish rinsing before we started evening chores. Like we often did, we were leaning on the silver bulk tank, catching up on each others’ days and pondering the world’s many problems when he said, “I don’t think there’s a future for you in dairy farming.”

He pulled out the latest milk check. Another price drop. Another meager check for the work that kept us grueling along from dawn til dusk. With feed prices climbing, milk prices dropping and a poor stroke of luck that meant needing to buy in some replacements, Dad had become a regular at our small-town bank. He was a sound farm manager and worked full-time at the local feed mill for the insurance and extra paycheck, but with milk prices on an ever dipping-and-diving rollercoaster, our chances of digging out looked slim.

So life changed course. Dad continued with the dairy farm, but my dreams shifted, and I found myself at UW-River Falls majoring in marketing with an animal science minor in homage to my roots. Then I landed in a newsroom, sharing the stories of farmers and other rural folks across Wisconsin. Eventually I signed on with Farmers Union and a chance to work on behalf of family farmers on the issues impacting their farms and rural towns.

A few years after I had left the farm, Dad sold the Split Ridge herd. I remember the dreary day spent following the cattle broker as he walked through the barn, eyeing up the cows I’d raised from calves, as he turned over in his mind which would bring the prettiest penny. And I remember all too well that emotional last milking, where dad and I again found ourselves gathered round the bulk tank, this time with my infant son, Blake, who slept peacefully in a corner of the milkhouse as Dad and I tearfully brought in the last milking units and hung them over the peg where they’d stay.

When the cattle trailer backed up beside the milkhouse, our big Brown Swiss, Brownie, was among the first to load. I paused to scratch her head one last time before nudging her across the gutter and out the door. One by one the cows filed out, closing a chapter on the farm.

A few years later I felt the same pang watching my uncles’ cows head out the door for the last time . Two farms erased from Wisconsin’s dairy industry. Two among thousands lost these past few years.

This week, the fates of many more Wisconsin farms may also have been sealed. A number of farmers reached into their mailboxes to find a generic letter from Grassland, announcing that as of May 1, the dairy would no longer be accepting their farm’s milk. The problem, according to Grassland, is a policy put in place by the Canadian government to discourage exports of ultra-filtered milk into the Canadian market, resulting in Grassland losing its market for about 1 million pounds of milk per day. Ironically, at the same time it is dropping these farmers, the Greenwood-based dairy is reportedly behind a 5,000-cow expansion of Cranberry Creek Dairy in Dunn County. At a 70-pound daily production average, that herd expansion would add 350,000 pounds a day to Grassland’s corporate-owned supply.

In mid-March, Nasonville Dairy also notified a group of producers that they were being bumped off. In a recent article in The Country Today, Marathon County farmer John Litza was quoted as one of the farmers struggling to find a market for his milk after being axed by Nasonville.

“We’ve had to beg and borrow to find any place to ship our milk to,” Litza is quoted. “All the plants tell me they have too much milk.” He believes some plants in the state have been buying excess milk from out of state and notes one plant near Green Bay reportedly has been picking up Michigan milk on the cheap, for $6 per hundredweight rather than paying $14 for Wisconsin milk.

Something seems wrong with this picture.

Some days I’m thankful for the foresight Dad had. A lifetime in the dairy industry told him that we were on a runaway train that was only headed for heartache. Other days I’m angry. Angry that I didn’t try to fight it out and do what I love, no matter how hard the struggle. But as I hear of those letters rolling in and see fear stirring among my friends who are dairy farming, I’m angry at a system that has been so broken for so many years. I’m saddened by a system that for far too long has exclaimed that “Bigger is better!” A system that promotes overproduction with programs like the Dairy 30x20 Initiative – but then lynches family farms when they’ve become too efficient at production.

To the tune of a single sheet of paper in the mailbox, a farm’s legacy – maybe even generations of sweat and tears – could come to a close.

Each of those farms that received a letter this week has a story; each is home to real human beings whose lives will be shattered if they can’t find a market for their milk. And they’re not alone. The newspapers have been riddled lately with ads for herd dispersals – with families losing their way of life, like we did at Split Ridge. The Grassland letters may mean more dispersals. When will we as dairy farmers get wise to the fact that the market "correcting itself" is just a euphemism for farms going out of business? Many point the blame at countries like Canada, who are implementing policies in an effort to better stabilize their own markets. Maybe instead of pointing fingers abroad we should reevaluate our own response to nosediving prices. A February 2017 report by the National Center for Dairy Excellence Milk shows that in the midst of price-killing oversupply, we increased milk production in the last year by 2.5 percent nationally, with 54,000 more cows and a 1.9 percent increase in milk production per cow. In January alone, the nation’s dairy herd grew by 6,000 head.

It is insanity to continue full throttle with production. We need to develop common-sense oversupply management measures that will responsibly balance the milk supply and take some of the gamble out of farming – milk supply management should not be achieved by processors abruptly dropping existing farmers. I believe that when milk goes down the road, farmers shouldn’t be losing money. I also believe farmers shouldn’t have to fear the walk down their driveway to the mailbox.

Farm groups across the state are hard at work, searching for processors who might be able to accept more milk from the farmers who were dropped. So far, the outlook is bleak, with many processors reporting full capacity. DATCP’s Wisconsin Farm Center has set up a help line for affected farmers to call: 800-942-2474.

In The Country Today article, Mark Stephenson, UW-Madison director of dairy policy analysis, said he doesn’t believe the “handful” of producers who received letters make the scenario symptomatic or a reason more widespread concern.

“This may be short-lived, but now we have a lot of production in our country, and we have lots of inventory,” Stephenson said. “Hopefully, by fall, we will see some real strengthening in prices. The main exporting countries are still well below a year earlier production; they’re starting to draw down on stocks.” He pointed to dairy demand in China and a few other importing countries that has been ticking upward. “Look for milk prices to firm through the summer and into the second half of the year,” he said. “We’ll get through this.”

From a farm girl who has stood by the barn door and watched the cows go, I’m not sure we all will.

Danielle Endvick is communications director for Wisconsin Farmers Union. She and her husband recently bought her family farm in Holcombe and are working to start a new chapter on the farm, where they’re raising their two young sons.