The author is a market analyst for Daily Dairy Report.

It won’t always be smooth sailing, though. Headwinds persist. Low to reasonable feed costs typically correlate with low milk prices. Milk powder inventories in the United States, Europe, and India remain burdensome. U.S. cheese stocks are record large. The dollar is also strong, making U.S. dairy products more expensive when priced in foreign currencies.

TWO DIFFERENT DIRECTIONS

And while Europe, New Zealand, and other dairy exporters are aggressively pursuing trade pacts to improve access to customers around the globe, the United States, for the most part, is moving in the opposite direction, eschewing the Trans-Pacific Partnership and levying tit-for-tat tariffs against China. After China raised border taxes on U.S. dairy products in July, the value of U.S. dairy product exports to China plunged to a nearly two-year low, down 27 percent from July 2017 and off 42 percent from April’s record-breaking shipments. The U.S. trade relationship with Mexico seems to be thawing, but the country’s retaliatory tariffs on U.S. cheese remain.

Despite these challenges, the current is pulling the U.S. industry toward a more favorable climate. The domestic appetite for dairy, particularly cheese, is strengthening. The economy is booming, wages are climbing, and consumers are spending with confidence. And after years of surplus, global dairy demand is helping to bring supplies into balance.

U.S. dairy product exports remain relatively strong, although they have softened from the record-breaking pace set in spring 2018. For now, cheese exporters are working with Mexican buyers to absorb tariffs and keep product moving. Both sides anticipate an eventual return to the more favorable border tax structure of a few months ago.

North of the border, the United States could win concessions from Canada on Class 7 milk. This contentious classification has allowed Canada to boost milk production, dump skim milk powder on an already crowded global market, reduce U.S. cream and butter imports, and completely cut off an outlet for ultra-filtered milk. If U.S. trade negotiators can win a compromise on Class 7, it would likely restore ultra-filtered milk processing lines in New York and Wisconsin and remove a discount vendor, Canada, from the global milk powder market.

The elimination of Class 7 would also support U.S. milk prices in general and Northeast and Great Lakes milk checks in particular. Despite artificially cheap product in Canada and stiff competition from Europe and New Zealand, U.S. milk powder exports thrive.

With demand for dairy products on the rise, slower growth in milk output will chip away at dairy product stockpiles. For years, Europe and the United States have added cows and boosted milk output, which has resulted in a global milk surplus.

Going forward, genetic improvements rather than higher cow numbers will drive production gains in these two major players. The world market can surely absorb the increase in production per cow, especially if it is partially offset by contraction in U.S. and European milk cow numbers.

Adverse weather and strained farm finances have jump-started a simultaneous slowdown in both regions. Dairy herds on both sides of the Atlantic suffered through a dreary spring and sweltering summer. Milk yields dropped accordingly, limiting the seasonal build in dairy product inventories.

Even if the weather improves, milk production is unlikely to surge. Dairy cow slaughter volumes are high and heifer prices are low, suggesting contraction will continue. In the United States, dairy producers coast to coast are selling out. The story is much the same in Europe.

MOVING FORWARD

As milk prices rise, some dairy producers will consider expansion. But first they will need to pay bills in arrears, catch up on any deferred maintenance, and return to a healthier relationship with their lenders.

The beef market offers some opportunity for producers to improve cash flows. Crossbreeding could slowly help rebuild equity, but it would also keep in check the number of dairy-breed heifers available to fill empty stalls.

A limitation

A shortage of processing capacity will also restrain expansion. True, processors have built new facilities and improved efficiencies at existing plants, but some older operations have been shuttered and a mismatch exists in areas where dairy producers might want to expand and where new milk would be welcomed.

High land values, an elevated cost of production, and the expense and scarcity of water in California will continue to shrink the dairy herd in the nation’s largest dairy state. Water issues in the Southwest and Mountain States will also likely deter extensive additions in these regions, and processing capacity remains inadequate in much of the Midwest and Northeast as evidenced by eroded milk premiums, a symptom of surplus raw milk.

Dairy producers will subtract any unfavorable basis from their blended milk prices as they evaluate whether to expand. Those in oversupplied regions will be hesitant to grow significantly without a ready market. Moreover, the tight labor market and lack of workers needed to build and staff a new dairy will further deter expansions.

ON THE HORIZON

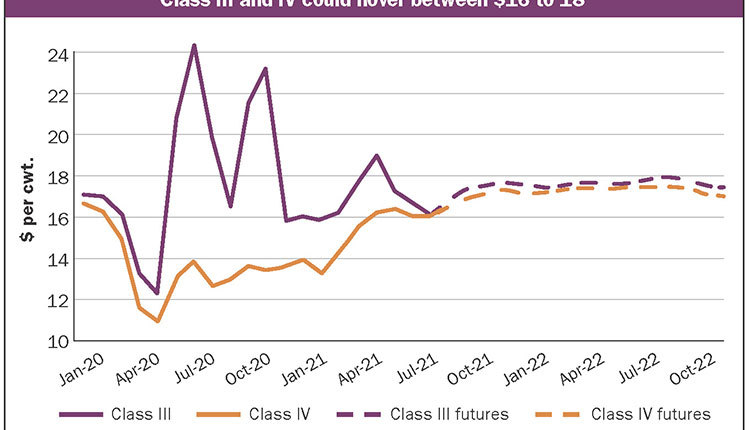

If milk prices were exuberant, dairy producers might overlook all these hurdles and build with abandon. But such enthusiastic expansion is unlikely in the near future.

Milk prices should climb, but they are unlikely to be sufficiently buoyant to foster a boom-and-bust cycle. Rather, dairy producers should hope for milk prices to improve to levels that can sustain profits on the farm without unduly throttling demand. At long last, the dairy industry may be on course toward a safe harbor.