Anyone involved in dairy farming knows the frustration of a mastitis infection. It’s costly — maybe your favorite cow was culled too soon or your milk premiums took a hit. One clinical mastitis case alone is shown to cost $444 during the first 30 days in milk.1

An important and often overlooked aspect of controlling mastitis is dry cow management. A well-planned dry cow program can help maintain quality milk production and set up a cow for a successful lactation.

In order to best prevent mastitis during the dry period, we should first understand the two high-risk times cows can contract an infection:

- Immediately after dry off

Right after a cow stops being milked, the udder will become engorged, and her quarters may leak milk. The teats are also no longer being dipped two to three times a day, and bacteria are not being flushed out from milking, making cows vulnerable to mastitis.

At dry off, producers will traditionally use an antibiotic to clear up any existing infections from the previous lactation, and to prevent new infections that may occur in the dry cow pen. Mastitis treatment during the dry period generally results in higher cure rates than during lactation, and it’s the most effective time to treat a subclinical infection.2 - The end of the dry period going into the next lactation

A cow’s udder will start to develop and produce colostrum near the end of the dry period. Once again, her udder will start to fill, and teats may leak. However, now the treatments that were used shortly after dry-off are below what we call the “minimum inhibitory concentration” to be effective against bacteria. Few antibiotics will provide full protection for the entire dry period.2

Teat sealants can play a valuable role in defending against mastitis throughout dry off. They provide a sterile, antibiotic-free physical barrier between the udder and its environment. Sealants also work well in conjunction with antibiotic therapy.

Producers can choose from both internal and external teat sealants:

- External teat sealants may only last five to seven days, and require regular visual inspection.2 When used effectively, they are applied twice; once at dry off, and then again before freshening. Depending on the number of applications, external sealants can quickly become labor-intensive and costly.

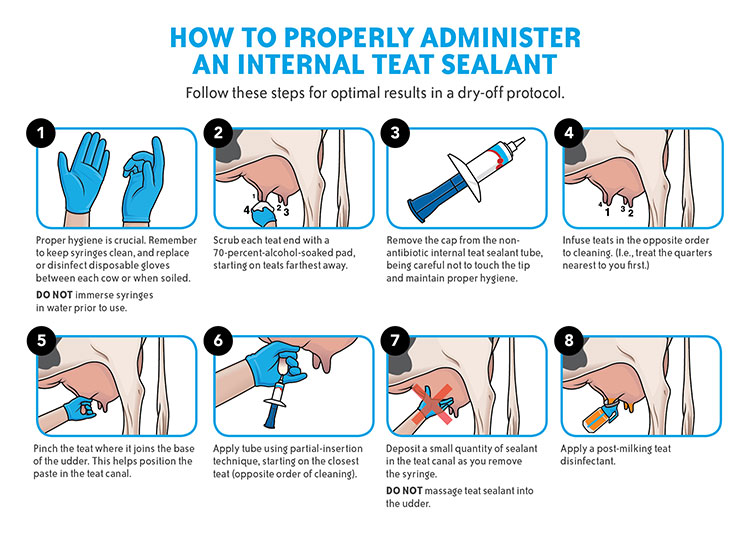

- Internal teat sealants have been designed to last across the entire dry period and simulate a cow’s natural first line of defense, the keratin plug, to seal the teat against harmful bacteria. But we need to ensure internal sealants are used properly. The teat end should be thoroughly sanitized before infusion. Without proper hygiene and preparation, organisms present on the teat end may be forced into the udder and cause infection, especially if Gram-negative bacteria are introduced.2

During administration (refer to Figure 1.), the area where the teat joins the udder should be pinched so the sealant is only applied into the teat cistern. Care should also be practiced at removal, stripping should continue until the majority of the sealant is gone. A color indicator, like a cool blue, that’s easy to distinguish from milk or mastitis can help ensure the majority of the sealant is stripped out.

Vaccination at dry off is another tool that can reduce the severity and incidence of mastitis.3 I recommend vaccinating all cows at dry-off, then giving a booster vaccine two to four weeks later. An effective mastitis vaccine should have a short meat withdrawal, and provide protection against E. coli, and endotoxemia caused by E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium.

Even with the best management practices in place, mastitis infections after calving do happen. In mild to moderate cases, producers can take a milk sample, culture and wait 24 hours for results before deciding to treat. Sampling can be done without a negative effect on cure rate or animal welfare. In 30 to 40 percent of the cultured samples, there are no bacteria present since the cow has eliminated the infection herself, so producers are only seeing inflammation.4,5,6 However, for severe mastitis cases, treat cows right away with an appropriate treatment protocol.

There are a number of resources available for producers looking to improve or refine their dry cow mastitis protocols. The National Mastitis Council is a global organization dedicated to mastitis control and milk quality. Its website (nmconline.org) offers helpful resources including recommended protocols, the latest mastitis research and milking tips. I would also encourage producers to look at resources available at their local university or extension groups.

Lastly, and most importantly, your herd veterinarian is your best mastitis prevention resource. They can help develop a control program tailored to your operation’s specific needs. A veterinarian can also provide treatment options that are approved for lactating cows, and give guidance on best practices for preventing antibiotic resistance. Successful mastitis management comes from a combination of factors such as good parlor management, proper cow handling, cleanliness, record keeping, vaccination and treatment protocols. Dry cow care is just one piece of the puzzle.

References:

1 Rollin E, Dhuyvetter KC, Overton MW. The cost of clinical mastitis in the first 30 days of lactation: An economic modeling tool. Prev Vet Med 2015;122(3):257–264.

2 National Mastitis Council. Dry-cow therapy. 2006. Available at: http://www.nmconline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Dry-Cow-Therapy.pdf. Pages 1–4. Accessed Dec. 9, 2018.

3 National Mastitis Council. A practical look at environmental mastitis. 2010. Available at: http://articles.extension.org/pages/11527/a-practical-look-at-environmental-mastitis. Accessed Dec. 9, 2018.

4 Hoe FG, Ruegg PL. Relationship between antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical mastitis pathogens and treatment outcome in cows. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;227(9):1461–1468.

5 Schukken YH, Zurakowski MJ, Rauch BJ, et al. Non-inferiority trial comparing a first-generation cephalosporin with a third-generation cephalosporin in the treatment of non-severe clinical mastitis in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2013;96(10):6763–6774.

6 Vasquez AK, Nydam DV, Capel MB, et al. Randomized non-inferiority trial comparing two commercial intramammary antibiotics for the treatment of non-severe clinical mastitis in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2016;99(10):8267–8281.

©2020 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., Duluth, GA. All Rights Reserved. BOV-1950-GEN0119