Two articles were referenced in the May 25, 2011 issue.

From the May 25, 2002 Hoard's Dairyman on page 389.

Click here to download the pdf. The article content is printed below.

From the May 25, 2005 Hoard's Dairyman on page 379

Click here to download the pdf. The article content is printed below.

Do your free stalls measure up?

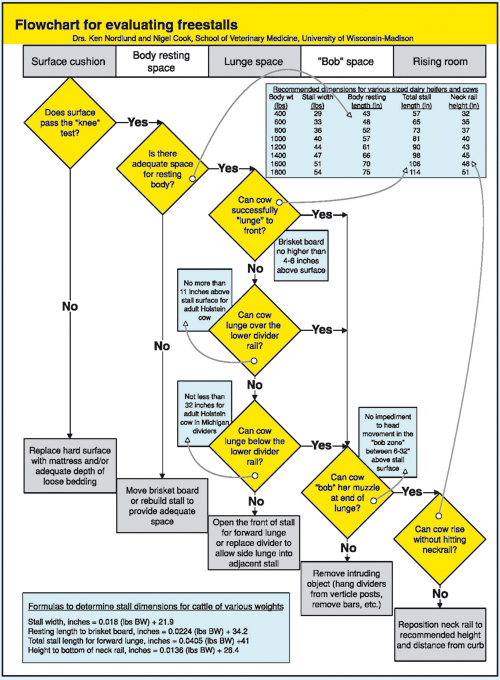

Today's high-producing cow needs a clean and comfortable place to rest. You can use this flowchart to analyze your stalls from a cow's perspective.

by Ken Nordlund, D.V.M., and Nigel Cook, D.V.M.

The authors are veterinarians and professors with the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Shortfalls in free stall design have long been significant risk factors for mastitis, lameness, and other injuries to cows. These problems are a direct result of dirty stalls, hard and rough stall surfaces, and incorrect location of divider bars.

There are many reasons that problem free stall barns exist. First, it has only been in the past 10 to 15 years that free stall design has focused on cow comfort and the actual space a cow needs to lie down and get up. This evolution of stall design has lead to many different stall types. Some require cows to lunge into a stall on either side of them; others force cows to lunge directly in front of them. Also, the addition of thick mattresses and the removal of loose bedding can cause dramatic changes in the distance between the stall surface and divider rails. These changes can turn a good free stall design into a cow comfort disaster.

Due to the wide variety in stall designs and the broad range of cow and heifer body sizes, we developed a comprehensive stall evaluation system based on the cow's functional needs. This system was developed from watching a cow as she lies down, rests, rises, and leaves the stall.

The system focuses on the following areas:

1. comfortable stall surface cushion

2. adequate body resting space

3. lunge room for her head to thrust and an unobstructed "bob-zone"

4. sufficient height below and behind neckrail

When looking at stall surface cushion, the surface must be comfortable enough to attract a cow to lie down in the stall, rather than elsewhere. In our opinion, the surface cushion is the single most important factor when determining free stall usage. Lying times in free stalls of 14 hours per day have been reported for deep straw beds, in contrast to only seven hours per day on unbedded concrete. The surface should be soft and moldable from front to back. Many mistakes in stall design can be tolerated if the bed is soft and comfortable.

A good way to check your surface cushion is to use a "knee test." First, the surface should mold to your knee as you kneel in the stall, and your knees should stay clean and dry. If they do, you can then rise slightly from the kneeling position and drop to your knees to see how soft the stall really is.

Sand is our preferred bedding material. Organic material such as wood shavings, sawdust, or straw works well in terms of comfort, but they will support bacterial growth if moisture is present, raising the risk for mastitis.

The next area to look at is the stall size. Is it large enough to provide adequate resting space for the cow? Defining the resting space in the front of a stall with a brisket-board helps to position the cow properly in the stall, reducing fecal contamination and lowering the chance of the cow getting trapped in the stall. The resting space is actually the area between the stall divider rails from the rear of the stall to where the stall surface meets the brisket board. This does not include the space needed for the cow's head or for lunging to get up.

Stall dimensions should be based on estimated cow size within the herd because there can be a wide variation among herds. The stalls should be fitted to the largest 25 percent of animals in a pen. The typical resting space in new barn construction today is 48 inches wide and 66 inches in length which will accommodate 1400-pound cows. You can refer to the chart above to get specific stall dimensions.

"Lunge and bob" room is the next critical factor when designing "cow-friendly" stalls. When cows stand up, they rise with their rear legs first. However, there are several important steps that happen first. A cow will first pull her front legs underneath her and elevate herself on her front "knees." She then lunges forward and "bobs" her muzzle downward, transferring the weight forward using her knees as a fulcrum. Then she is able to get up using her rear legs. She completes the motion by extending her front feet and then balancing her weight.

If a cow is unable to rock forward to lunge and bob, her rear legs must lift more weight. The inability to transfer weight from the rear legs, combined with a slippery stall, cause a variety of problems to cows housed in these stalls.

The final point is adequate room to rise below the neckrail without obstruction. The neckrail acts to provide structural support for the dividers, and they also help position the cow while she is standing in her stall so that she does not soil it with urine and feces. The neckrail provides the most structural support when it is placed as far toward the rear of the stall as possible. However, the more the neckrail is moved to the rear of the stall, the more it interferes with cow entry and exit, resulting in cows standing half-in and half-out of the stalls.

When a brisket board is used, the neckrail should be directly above the board or further toward the front. If the rail has a shiny rubbed under surface, it is incorrectly located. Cows are frequently hitting the rail when they get up.

By using the accompanying flowchart, you can easily evaluate your free stall design. Then, you can see what's working well and what isn't and start to make the appropriate changes.

How does your farm rate on cow comfort?

by Kathy Zurbrigg

The author is in veterinary science with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Fergus.

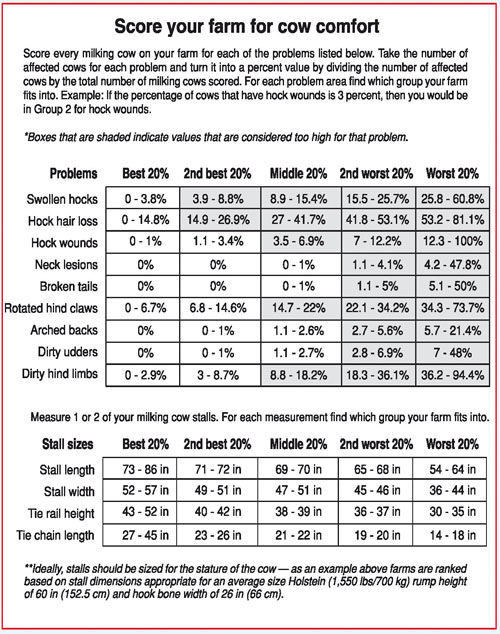

How are today's cows fairing in tie stall barns? To determine the answer to that question, we conducted a survey to examine the relationship between tie stall size and cow welfare. More than 18,000 milking cows on 317 tie stall dairy farms were scored for problems including lameness, injury, and dirtiness. The percentage of each herd affected with the problem was determined, and then farms were grouped from the best to the worst for each category.

Since stall design plays such a key role, measurements such as stall length, width, tie rail height, and tie chain length also were recorded. Again, farms were grouped from best to worst, based on size requirements for an "average-sized" 1,550-pound Holstein cow. This information is summarized in the chart.

What is normal?

Many producers do not often visit other farms, making it difficult for them to gauge what a "normal" rate of lameness or injury is. The chart was created to encourage producers to score their cows and compare themselves to other dairies. Farms with scores that fall within the shaded areas have reason to be concerned - improvements to cow comfort are needed.

We also tried to discover which aspects of tie stall design affect dairy cow lameness, injury, and cleanliness. Certain stall dimensions seemed to lead to each of these problems. Although these problems often have many components, making changes to stall dimensions should improve cow comfort.

Specific stall sizes should be based on the size of the cow. Equations to determine appropriate electric trainer placement and stall dimensions can be found in a fact sheet by Dr. Neil Anderson on the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food's website at: http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/livestock/dairy/facts/info_tsdimen.htm

Signs of problems . . .

Hock problems are often the most noticeable cow comfort issue. Hock lesions include hair loss, swollen hocks, and open or scabbed wounds. All can result from small stalls and a restriction on the space a cow has to get up and lie down. Short tie chains and stalls with a poorly positioned electric trainer also caused cows to have more hock lesions. Lengthening tie chains and ensuring the electric trainer has proper height and forward location (4 inches above chime and 47 to 48 inches forward of gutter on 70- to 72-inch stall bed) give cows more room to perform natural movements in rising and lying down.

While the current study did not look at stall surface characteristics, making sure that the stall surface is not slippery and is well-cushioned also cuts down on hock injuries. This may involve replacing old, worn-out mats and mattresses and using more bedding.

Both tie stall and free stall cows can have abrasions on the back of the neck. In tie stalls, neck lesions were found to be related to the height of the tie rail, with cows having more lesions if they had a tie rail between 39 and 45 inches high. These lesions are caused by the cow hitting her neck on the underside of the tie rail while rising or eating, and the damage can range from hair loss to large wounds. Raising the tie rail above 45 inches for the cow and adding more bedding to improve her footing should reduce the number of neck lesions.

Broken tails are also a concern. Most often they come from poor cattle handling. Using the "tail twist" (grabbing the tail midshaft and twisting) to get a cow to rise or move can result in broken vertebrae in the tail. This causes pain to the cow, and, depending on the location of the break, can limit tail motion. Farms that had high numbers of broken tails also had more cows with dirty udders and hind limbs. This may be an indicator of a poor attitude towards cow care. Other methods of restraint must be used.

Small stalls cause lameness . . .

Lameness is also an important cow comfort issue, yet often overlooked in tie stall herds. To provide relief from sole pain and/or the pressure of overgrown claws, cows will rotate the affected hind feet outwards to transfer weight from the outside to inside claw. Short stalls cause more claw problems. Recent studies also have shown cows that spend a lot of time standing are more prone to claw health problems and lameness.

Lengthening the stalls will encourage cows to spend more time resting and allow them to lie straight in the stall with their whole body on the stall bed. This should reduce lameness. Cows that stand in the gutter also have more hoof problems in the hind feet. Keeping the hind claws drier by adding more bedding and cleaning stalls more frequently should reduce lameness.

While dirty cows are not directly a cow comfort issue, in this study, manure on the hind legs and udder were linked to higher bulk tank somatic cell counts (BTSCC). To keep hind limbs cleaner, give cows more room to rise and lie down in an unrestricted manner. Lengthening the tie chain, hanging the electric trainer in the proper position, and increasing the stall length all help improve hind leg and udder cleanliness. The addition of more bedding and cleaning stalls more than once a day also keeps cows cleaner.

As well as improving cow comfort, the study results suggest that there are economic benefits to making these recommended stall changes. Wider stalls lead to lower bulk tank SCC and more milk shipped per cow. Wider stalls allow cows to rest comfortably and spend more time lying down, both important for improved health and production. Use the chart to assess cow comfort on your farm and indicate areas where changes should be made to improve both the welfare and productivity of the herd.

020525_389