On calving day, cows will suddenly lose 20 to 30 grams of calcium to the udder for the production of colostrum, which is about two to three times the amount of calcium lost compared to the day prior to calving. This sudden and urgent demand for calcium sends the cow into negative calcium balance.

Subclinical hypocalcemia (SCH) is defined as low blood calcium concentrations without obvious clinical signs and unlike clinical milk fever, SCH is becoming more prevalent in today’s dairy herds.

As the cow’s blood calcium levels decline around calving, her body responds by secreting what is called a parathyroid hormone, or PTH, into the bloodstream. The PTH hormone increases bone mobilization – the natural process by which the body dissolves part of the bone in the skeleton in order to maintain or raise calcium levels. It also increases intestinal absorption, and decreases urinary excretion of calcium in response to hypocalcemia.1

Mobilization of calcium from the cow’s skeleton is called lactational osteoporosis. Amazingly, a cow loses about 9 to 13 percent of her skeletal calcium in the first month of lactation but she can restore the lost calcium to her skeleton later in lactation.2 In the short term, this stresses the cow’s bones, but it allows her to maintain normal blood calcium levels over the long term.1

“Most cows will revert back to positive calcium balance by six to eight weeks post-calving, meaning the calcium intake now equals or exceeds calcium outflow,” said Dr. Garrett Oetzel, DVM MS, professor at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison. “However, she can draw on her bone calcium for up to four months into lactation, including during times of stress or low feed intake.”

The negative consequences of SCH include reduced milk yield,3,4 immune suppression,5 higher concentrations of blood non-esterified fatty acids,6 increased risk for metritis,5 increased risk for coliform mastitis,7and an increased risk for early removal from the herd.8 The exact point in blood calcium concentration at which negative consequences start is termed the cutpoint.

Dr. Brian Miller, senior professional services veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim said SCH can be detected with the help and advice of your herd veterinarian. “Your veterinarian can help retrieve blood samples of recently fresh cows to determine blood calcium concentrations,” he said. These test results can be used to build and execute an economically viable prevention strategy for SCH on your dairy operation.

“Given the high prevalence of SCH and the high losses associated with this disease, the focus must be on prevention,” said Dr. Miller. “There are two main approaches to prevention of SCH - dietary manipulation pre-calving and strategic oral calcium supplementation post-calving. Neither approach is sufficient by itself to prevent all of the negative impacts of SCH; however, using both approaches together will minimize the impacts of SCH as much as possible.”

Dr. Oetzel said the best oral calcium sources are acidogenic salts such as calcium chloride and calcium sulfate.9,10 “These salts provide additional calcium for absorption from the gut, plus they extend the time period that the cow is in a relatively acidic state.”11 Because calcium chloride and calcium sulfate invoke an acidogenic response in the cow, this enhances the cow’s responsiveness to PTH and improves her ability to mobilize calcium from her own bone.

“We see a double effect when using a good oral calcium product – both rapid absorption of the oral calcium and mobilization of the cow’s own skeletal calcium,” said Dr. Oetzel. “Blood levels peak 30 to 60 minutes after administration. Bovikalc® extends calcium release for 6 to 12 hours because of the bolus formulation.11”

Get the best economic response to oral calcium supplementation

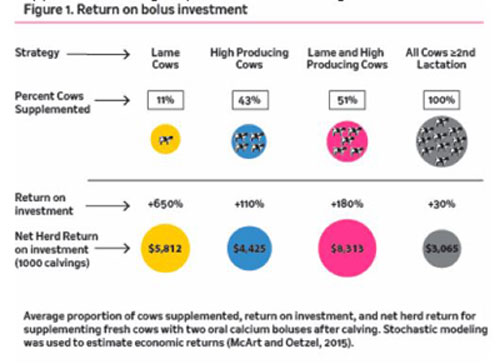

An in-depth evaluation was conducted of the economic benefits of administering one Bovikalc® calcium supplement to dairy cows at calving, and then again the day after calving.12 Expected economic returns from different supplementation groups are outlined in Figure 1.

Supplementing high producing cows and lame cows had the highest net return on investment. If using this strategy, a dairy producer would supplement 51 percent of the fresh cows and would have an average return on investment of 180 percent (i.e., an investment of $1.00 would return the $1.00 invested plus an additional $1.80).

Supplementing only lame cows had an exceptionally high average return on investment (650 percent), but only a small percent of the cows were supplemented. Because only 11 percent of cows were supplemented, the average net herd return from this strategy was less compared to supplementing both the high producing and lame cows.

Supplementing all second and greater lactation cows provided a 30 percent return on investment (i.e., each $1.00 invested returned the $1.00 plus an additional $0.30). Since this approach involves supplementing all cows, the average net herd return on investment was substantial, but lower than if only the high-producing and lame cows were supplemented.

“Supplementing high producing cows and lame cows has the highest net return on investment, but blanket use of BOVIKALC on second and greater lactation cows is often preferred by the end user. It is a much simpler strategy to implement and does not require locomotion scoring or creating a list of cows by milk production,” Dr. Miller concluded.

ABOUT BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM

Boehringer Ingelheim

Innovative medicines for people and animals have for more than 130 years been what the research-driven pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim stands for. Boehringer Ingelheim is one of the industry’s top 20 pharmaceutical companies and to this day remains family-owned. Day by day, some 50,000 employees create value through innovation for the three business areas human pharmaceuticals, animal health and biopharmaceutical contract manufacturing. In 2016, Boehringer Ingelheim achieved net sales of around 15.9 billion euros. With more than three billion euros, R&D expenditure corresponds to 19.6 percent of net sales.

Social responsibility comes naturally to Boehringer Ingelheim. That is why the company is involved in social projects, such as the “Making More Health” initiative. Boehringer Ingelheim also actively promotes workforce diversity and benefits from its employees’ different experiences and skills. Furthermore, the focus is on environmental protection and sustainability in everything the company does.

More information about Boehringer Ingelheim can be found on www.boehringer-ingelheim.com or in our annual report: http://annualreport.boehringer-ingelheim.com.

References

1. Goff JP. The monitoring, prevention, and treatment of milk fever and subclinical hypocalcemia in dairy cows. Vet J 176:50-57, 2008.

2. Ellenberger HB, Newlander JA, Jones CH. Calcium and phosphorus requirements of dairy cows. II. Weekly balances through lactation and gestation periods. Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin 342 June 1932.

3. Chapinal N, Carson ME, LeBlanc SJ, Leslie KE, Godden S, Capel M, Santos JE, Overton MW, Duffield TF. The association of serum metabolites in the transition period with milk production and early-lactation reproductive performance. J Dairy Sci 95:1301-1309, 2012.

4. Guard CL. Fresh cow problems are costly; culling hurts the most: Hoard's Dairyman 141:8, 1996.

5. Martinez N, Risco CA, Lima FS, Bisinotto RS, Greco LF, Ribeiro ES, Maunsell F, Galvao K, Santos JE. Evaluation of peripartal calcium status, energetic profile, and neutrophil function in dairy cows at low or high risk of developing uterine disease J Dairy Sci 95:7158-7172, 2012.

6. Reinhardt TA, Lippolis JD, McCluskey BJ, Goff JP, Horst RL. Prevalence of subclinical hypocalcemia in dairy herds. Vet J 188:122-124, 2011.

7. Curtis CR, Erb HN, Sniffen CJ, Smith RD, Powers PA, Smith MC, White ME, Hillman RB, Pearson EJ. Association of parturient hypocalcemia with eight periparturient disorders in Holstein cows. J Am Vet Med Assoc 183:559-561, 1983.

8. Seifi HA, Leblanc SJ, Leslie KE, Duffield TF. Metabolic predictors of post-partum disease and culling risk in dairy cattle. Vet J 188:216-220, 2011.

9. Goff JP, Horst RL. Oral administration of calcium salts for treatment of hypocalcemia in cattle. J Dairy Sci 76:101-108, 1993.

10. Goff JP, Horst RL. Calcium salts for treating hypocalcemia: carrier effects, acid-base balance, and oral versus rectal administration. J Dairy Sci 77:1451-1456, 1994.

11. Sampson JD, Spain JN, Jones C, Carstensen L. Effects of calcium chloride and calcium sulfate in an oral bolus given as a supplement to postpartum dairy cows. Vet Ther 10:131-139, 2009.

12. McArt JA, Oetzel GR. A stochastic estimate of the economic impact of oral calcium supplementation in postparturient dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 98:7408-7418, 2015.