Over the past decade, inseminations to sexed semen have grown from 9% of Holsteins and 23% of Jersey heifers and cows in 2009 to 21% of Holstein females and 46% of Jersey females in 2020. This shift to sexed semen, along with terminal breeding using beef semen, has diminished services to conventional dairy semen.

Taking a step back, beef semen use in the dairy industry was nonexistent until the market for dairy bull calves shifted downward. Today, over 27% of Holstein and 34% of Jersey females are inseminated with beef semen. In fact, inseminations with sexed and beef semen are staples in mating strategies to produce genetically elite heifer replacements and greater market value crossbred calves.

Initially, low fertility

When sexed semen was first introduced in the marketplace, the recommendation was that the product be solely used for first or second inseminations of heifers based on detection of estrus. Farmers also were advised to not use sexed semen in lactating cows because of the poor fertility compared to heifers.

Over the past two decades, the development of fertility programs for lactating cows improved pregnancies per A.I. and service rates drastically, thereby improving fertility in high-producing dairy cows. Fertility programs such as double ovsynch for first service raised pregnancies per A.I. by 10 percentage points with conventional semen compared to cows inseminated from a synchronized estrus at a similar days in milk (DIM) range. The development and adoption of fertility programs has allowed for sexed semen inseminations in cows with greater genetic merit.

Conception rates with sexed semen are 80% to 90% of conventional semen despite increased fertility of cows from synchronized ovulation protocols. The sexing process is a more time-consuming process that exposes sperm to more stress than conventional semen processing. Adaptations have been made to the sexing process in the technology and media used, but reduced fertility still persists in randomized controlled studies. Further, raising sperm numbers per straw does not enhance fertility of sexed semen. So, what can be done to bolster conception rates with sexed semen?

Delay insemination

One idea to improve fertility with sexed semen is to inseminate cows closer to presumed time of ovulation because of the damage sexed sperm endure from the sexing process. In observational studies, delaying insemination with sexed semen relative to the onset of estrus determined by activity monitors improved pregnancies per A.I. in lactating Jersey cows. A challenge with inseminating cows based on detection of estrus is the variability of estrus, because high-producing lactating dairy cows exhibit decreased estrous expression, a longer interval from the onset of estrus to ovulation, and a shorter duration of estrus.

Since estrus is so variable, it is challenging to determine whether delaying insemination with sexed semen improves fertility because timing of ovulation is not precisely controlled. For this reason, we chose to examine this new idea of delaying insemination with sexed semen using a synchronized breeding protocol in which timing of ovulation is precisely controlled.

We conducted a study to determine the effect of altering the time of induction of ovulation relative to timed artificial insemination using sexed semen. We predicted that induction of ovulation earlier relative to timed A.I., inseminating closer to presumed ovulation, would improve pregnancies per A.I.

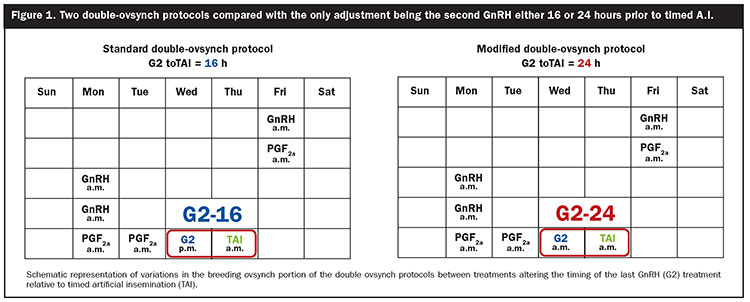

For first service, 730 first-lactation Holstein cows across three U.S. farms were submitted to a double ovsynch protocol for first timed A.I. Cows were randomized to receive the last GnRH treatment of the breeding ovsynch portion of the double ovsynch protocol (G2) either 16 (G2-16) or 24 (G2-24) hours before timed A.I. To vary the interval from induction of ovulation to timed A.I., G2-16 cows received G2 in the p.m. the day before timed A.I. currently done in most double ovsynch protocols, whereas G2-24 cows received G2 in the a.m. the day before timed A.I., and timed A.I. occurred in the a.m. the day after G2 for all cows (Figure 1).

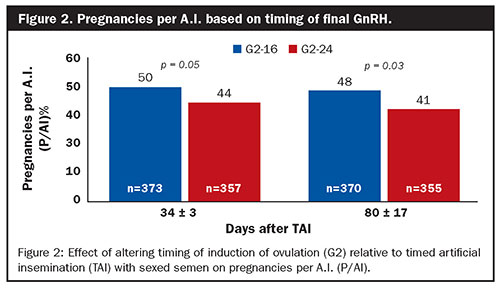

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, G2-24 cows had fewer pregnancies per A.I. than G2-16 cows 34 ± 3 (44% versus 50%) and 80 ± 17 (48% versus 41%) days after timed A.I. (Figure 2). This disagrees with observational studies that delaying insemination with sexed semen based on detection of estrus increased pregnancies per A.I.

In a recent study with virgin heifers, delaying timed A.I. with sexed semen in a five-day CIDR-synch protocol did not improve fertility. Delaying insemination relative to the onset of estrus may step up pregnancies per A.I. with sexed semen and potentially conventional semen because of the longer interval from the onset of estrus to ovulation. A reduction in pregnancies per A.I. was observed in earlier studies, identifying the optimal time interval from G2 to timed A.I. with conventional semen as 16 hours from G2 to timed A.I. with the greatest pregnancies per A.I. There was a 4 percentage point drop when G2 was 24 hours before timed A.I.

By altering the timing of G2, this reduced time for sperm transport and capacitation, a biochemical process a sperm undergoes to fertilize an oocyte, for G2-24 cows and may be insufficient. Further, with this experimental design we unintentionally manipulated other factors including time for luteal regression affecting estradiol and progesterone concentrations and ovulatory follicle size that could affect fertility. In this design, G2-24 cows had 8 hours less for luteal regression that could have decreased ovulatory follicle size by 1 mm, thereby creating a smaller corpus luteum producing less progesterone after timed A.I. and potentially reducing fertility.

Pregnancy loss was 5% and 6% for G2-24 and G2-16 cows, respectively, and did not differ between treatments. Fetal sexing was diagnosed using transrectal ultrasonography at the pregnancy recheck on two of the three farms, and the proportion of heifers was approximately 90% for each treatment.

Timing is key

Delaying inseminations with sexed semen may improve pregnancies per A.I. based on detection of estrus, but not in a synchronized ovulation protocol where timing of ovulation is precisely controlled. The gain in fertility from delaying inseminations with sexed semen based on detection of estrus is likely because of the longer interval from the onset of estrus to ovulation and shorter duration of estrus.

Extending the interval from induction of ovulation to timed A.I. reduced pregnancies per A.I. because of time differences for sperm transport and capacitation as well as differences in hormonal concentrations at key points in the synchronization protocol. With sexed semen, it is more critical to inseminate at the right time relative to ovulation rather than closer to ovulation.