The incorporation of a robust diagnostic strategy has been promoted heavily in recent years as a way to identify the predominant pathogens causing mastitis in a herd. Such a program is critical to support treatment, management and culling decisions.

Yet, when you're trying to determine the best course of treatment, a negative mastitis culture result can be quite frustrating. "If we don't know what pathogen we are dealing with, it's like driving blindfolded," noted Nicole Steele, with New Zealand's DairyNZ. In these situations, PCR testing can shed some light.

"Simply put, PCR (polymerase chain reaction) is molecular photocopying; it amplifies short strands of DNA," noted Steele at the National Mastitis Council annual meeting. PCR detects the DNA of any organism, alive or dead, that is present in milk. Cultures are only capable of growing viable bacteria.

While it is faster than culturing and requires a lesser pathogen load for detection, a PCR test does not tell us about the bacteria's viability and comes with a higher price tag. Therefore, asked Steele, is it practical?

Her answer: It depends on how it fits into a herd's overall monitoring strategy.

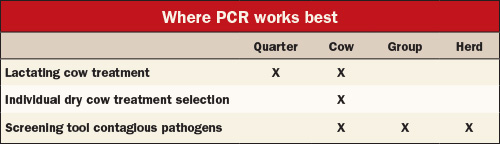

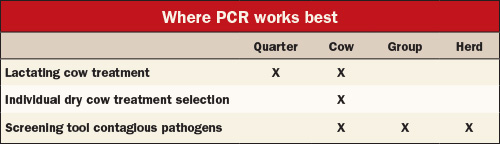

Instead, suggests Steele, PCR testing on quarter samples may be considered during a clinical mastitis outbreak, to guide future treatment decisions, in cases where treatment appears to fail or when culture fails to detect the presence of any pathogen.

Beyond the quarter, composite samples including milk from all functional quarters of a cow may be collected and pooled to reduce costs, or collected routinely as part of herd monitoring programs. Samples collected during herd test are best suited to identify and screen for contagious mastitis pathogens. Since routine herd test samples also provide production and somatic cell count data, PCR tests can be applied to monitor infection levels over time.

Group sampling offers the ability to monitor several different groups within a herd. The sampling method must produce a sample that is truly representative of the whole group, rather than the last few cows in the milk line. The effects of dilution on pooled samples were studied in Australia. Provided that at least one cow in a group of up to 1,000 cows was moderately to highly infected, the sensitivity of the assay was similar to that achieved in individual cow testing.

Collection of bulk tank milk samples enables regular monitoring of contagious pathogen prevalence in herds at relatively little cost. At this level, PCR testing can be used to screen for contagious pathogens, as an initial step in a mastitis investigation or to prevent the introduction of bacteria into a herd from purchased animals.

While the PCR assay has a number of applications from the quarter level up to that of the herd level, noted Steele, it is not yet a replacement for culture.

The author , Amanda Smith, was an associate editor and an animal science graduate of Cornell University. Smith covers feeding, milk quality and heads up the World Dairy Expo Supplement. She grew up on a Medina, N.Y., dairy, and interned at a 1,700-cow western New York dairy, a large New York calf and heifer farm, and studied in New Zealand for one semester.

Yet, when you're trying to determine the best course of treatment, a negative mastitis culture result can be quite frustrating. "If we don't know what pathogen we are dealing with, it's like driving blindfolded," noted Nicole Steele, with New Zealand's DairyNZ. In these situations, PCR testing can shed some light.

"Simply put, PCR (polymerase chain reaction) is molecular photocopying; it amplifies short strands of DNA," noted Steele at the National Mastitis Council annual meeting. PCR detects the DNA of any organism, alive or dead, that is present in milk. Cultures are only capable of growing viable bacteria.

While it is faster than culturing and requires a lesser pathogen load for detection, a PCR test does not tell us about the bacteria's viability and comes with a higher price tag. Therefore, asked Steele, is it practical?

Her answer: It depends on how it fits into a herd's overall monitoring strategy.

Instead, suggests Steele, PCR testing on quarter samples may be considered during a clinical mastitis outbreak, to guide future treatment decisions, in cases where treatment appears to fail or when culture fails to detect the presence of any pathogen.

Beyond the quarter, composite samples including milk from all functional quarters of a cow may be collected and pooled to reduce costs, or collected routinely as part of herd monitoring programs. Samples collected during herd test are best suited to identify and screen for contagious mastitis pathogens. Since routine herd test samples also provide production and somatic cell count data, PCR tests can be applied to monitor infection levels over time.

Group sampling offers the ability to monitor several different groups within a herd. The sampling method must produce a sample that is truly representative of the whole group, rather than the last few cows in the milk line. The effects of dilution on pooled samples were studied in Australia. Provided that at least one cow in a group of up to 1,000 cows was moderately to highly infected, the sensitivity of the assay was similar to that achieved in individual cow testing.

Collection of bulk tank milk samples enables regular monitoring of contagious pathogen prevalence in herds at relatively little cost. At this level, PCR testing can be used to screen for contagious pathogens, as an initial step in a mastitis investigation or to prevent the introduction of bacteria into a herd from purchased animals.

While the PCR assay has a number of applications from the quarter level up to that of the herd level, noted Steele, it is not yet a replacement for culture.

The author , Amanda Smith, was an associate editor and an animal science graduate of Cornell University. Smith covers feeding, milk quality and heads up the World Dairy Expo Supplement. She grew up on a Medina, N.Y., dairy, and interned at a 1,700-cow western New York dairy, a large New York calf and heifer farm, and studied in New Zealand for one semester.