Recognizing the difference between infection and inflammation can help cut costs and antibiotic use

“When you get kicked by a horse, what happens?” asked Linda Tikofsky, DVM, senior associate director of dairy professional veterinary services for Boehringer Ingelheim. “It’s going to swell up, maybe get red. But do you have an infection? Would you take antibiotics for your swelling? Probably not. You know the trauma you’re experiencing is most likely just inflammation.”

The same goes for a case of mastitis. The visible signs in the cow, such as a swollen, red udder and abnormal milk, aren’t actually the mastitis infection; it’s the inflammation, or the body’s response to infection.

Inflammation does not equal infection.

Inflammation is often the first sign of mastitis, but it should not determine whether treatment is necessary or dictate the length of treatment. Recognizing the difference between inflammation and infection can save time, antibiotic costs and promote judicious antibiotic use. When we see signs of inflammation, before reaching for antibiotics, consider doing the following:

1. Culture.

For mild to moderate mastitis cases, on-farm culturing helps us identify the right animals to treat, as not all cases require or respond to antibiotics. Dr. Tikofsky explains that if she were to culture 100 cows with mastitis, the results would usually follow the 30-30-30 rule:

- 30% no-growth: A no-growth case means that the cow has cleared the infection on her own, and does not need antibiotic treatment.

- 30% Gram-negative: Most Gram-negative mastitis cases, including those caused by E. coli, will self-cure, and antibiotic treatment will not alter the outcome.1

- 30% Gram-positive: Gram-positive mastitis cases do require antibiotic treatment, and can become chronic if left untreated.

“If we adopt a culture-based system and stop treating Gram-negative and no-growth cases, we can reduce mastitis treatment by 60 percent,” asserted Dr. Tikofsky. “When dealing with a Gram-positive infection, a short-duration mastitis therapy can eliminate the infection, and reduce the length of time cows spend in the hospital pen.” A veterinarian is an important resource to help set up a culturing system and interpret results.

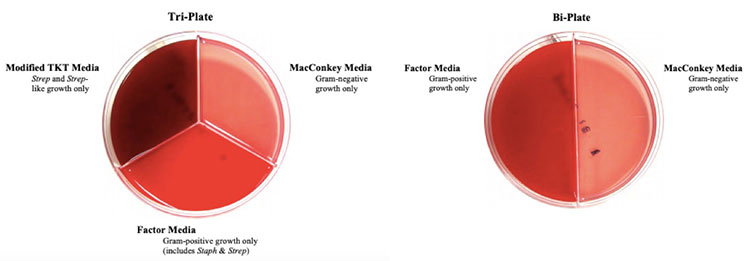

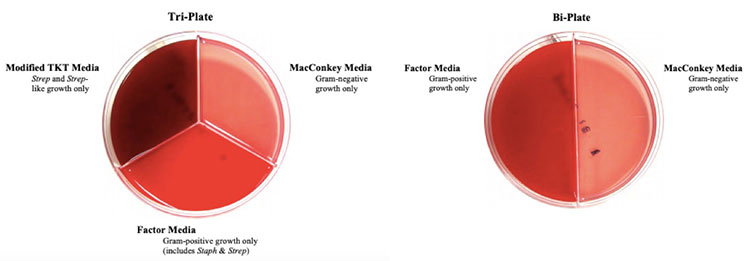

Figure 1. Tri-plate and bi-plate on-farm culture options. These plates make it easy to categorize mastitis as a no-growth, Gram-positive or Gram-negative case quickly and economically.

2. Treat the infection, not the inflammation.

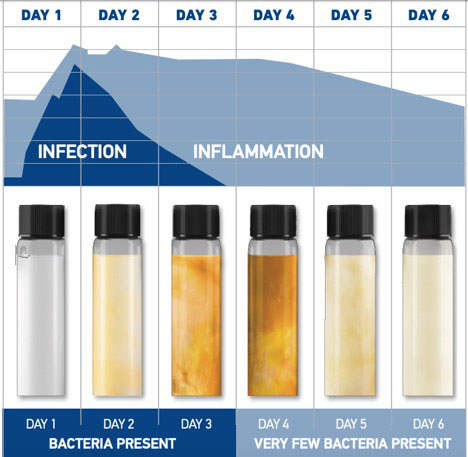

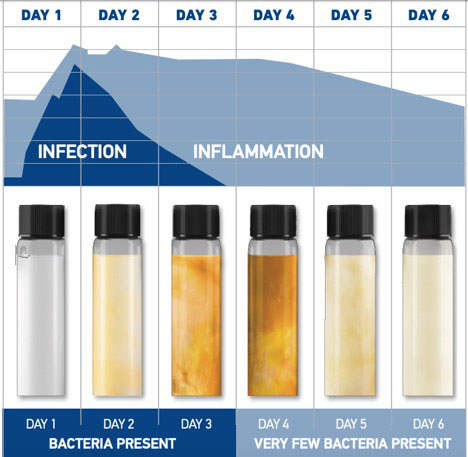

Figure 2. Bacteria peaks early in mastitis cases, and inflammation can last for days after the infection is resolved.

When pathogens are introduced into the udder, the cow’s immune system responds with inflammation by sending in white blood cells (increased somatic cell count) to combat the infection. These white blood cells release a number of chemicals that trigger the signs of inflammation such as swelling, redness and abnormal milk. While the initial infection is usually resolved in the first 24–48 hours (either on its own or due to treatment), the signs of mastitis, or inflammation, may take four to six days to disappear (see Figure 2). During this time, the body is eliminating the products of inflammation such as dead bacteria and somatic cells. On most dairies, the standard practice is to treat until milk returns to normal (when the inflammation is gone), which is why five-day treatment regimens have become common. However, this may be leading producers to over-treat with antibiotics. Producers can reduce antibiotic use by only treating until the infection is gone with a two-treatment or three-treatment regimen.

3. Trust the label.

One of the most common concerns Dr. Tikofsky hears from producers is that the cow still has symptoms after they’ve administered antibiotics. “The best piece of advice that I can offer is to trust the label,” she said. “We need to be patient, ignore the abnormal milk and not intervene again until the milk withhold period is up. I will wager that 75 percent of those cows will be ready to go back into the milking string after the first round of treatment. It can be tempting to give more antibiotics to a cow whose milk is still abnormal but every time that cow is infused with a tube, we are giving bacteria a window of opportunity to cause another infection.”

4. Keep good records.

Records can help producers track mastitis relapse rates. A relapse is an infection in the same quarter that happens again 14 days or later. “We want less than a 30 percent relapse rate,” Dr. Tikofsky emphasized. “These records can help producers make thoughtful decisions about which animals should be culled. Ideally, one person would be in charge of keeping records on a dairy software program.” She added, “It may not make economic sense to treat a cow that has chronic conditions.” Protocols and treatment records should be reviewed with a veterinarian at least annually.

“As long as we have a cow that is not physically sick, we have the opportunity to make an educated decision about what to do with her,” concluded Dr. Tikofsky. “The next time a cow shows signs of mastitis, work with your veterinarian to set protocols in place to respond to the infection appropriately.”

Reference:

1 Hess JL, Neuder LM, Sears PM. Rethinking clinical mastitis therapy, in Proceedings. 42nd Annual Meeting Nat’l Mastitis Council 2003:372–373.

©2020 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc., Duluth, GA. All Rights Reserved.

US-BOV-0077-2020