That’s also true in how we are able to care for our dairy cattle. Animal scientists and veterinarians continue to learn more about the cow’s physiology, while health professionals develop new vaccines and targeted treatments to best cure illnesses. And farmers are interacting with their animals every day to pick up on herd changes and efficiently use the prevention tools and treatments available.

Here at the Hoard’s Dairyman office, we have decades of this research and the evolutions of dairy farm management recorded in books and old issues of the magazine. We recently found a copy of one of the first books we published: the Herd Health Guide in 1964. Much of its guidance remains true today, but there’s also plenty that reminds us just how far our industry has come.

For example, removing horns is still necessary on most dairies, and we aim to do it early in a calf’s life and provide pain medication. It may seem surprising that in the 1964 book, caustic sticks and pencils (“Pastes may be substituted for the stick and they are preferred by some”) are the first dehorning method explained. Anesthesia is even recommended. On the next page, though, we read that “Electric dehorning is fast gaining popularity” and that when clipping horns off of animals older than two months, some skin should be removed, too. We have certainly advanced in our care and understanding of these young animals.

The biggest difference on today’s dairy farms compared to those of the 1960s might be the absence of bulls. The Herd Health Guide provides plenty of information for dairy farmers of that era to keep bulls healthy, in good condition, and safe. An entire page is even dedicated to explaining how to best tie up a bull and how to build a safe pen, so it avoids tearing its nose ring out.

Many technology advancements have made life easier for dairy farmers. For example, look at the manpower required to trim the hooves of this animal. Today, one person can do the job. We can also find cows ready to be bred with tools from simple tail paint to advanced activity monitors instead of turning cows out to pasture in the hopes of catching them in heat, as this book describes.

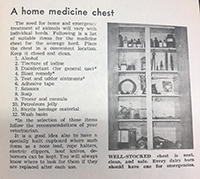

There’s emphasis on keeping housing “dry and draft-free.” The section on calfhood diseases looks much the same as one written today would, with scours covered first and a reiteration of the importance of delivering colostrum. And of course, even in 1964, mastitis was “the number one herd health problem in the United States” and cost dairy farmers “more money than all other diseases combined.” A well-stocked medicine cabinet was key to helping combat common illnesses.

Katelyn Allen joined the Hoard’s Dairyman team as the Publications Editor in August 2019 and is now an associate editor. Katelyn is a 2019 graduate of Virginia Tech, where she majored in dairy science and minored in communication. Katelyn grew up on her family’s registered Holstein dairy, Glen-Toctin Farm, in Jefferson, Md.