On my drive to work today, my mind was swirling with different thoughts, tasks I should complete, and some lingering stress from a rushed morning of getting everyone ready and out the door. As I approached Fort Atkinson, a familiar smell wafted into my car – the smell of fresh cut alfalfa.

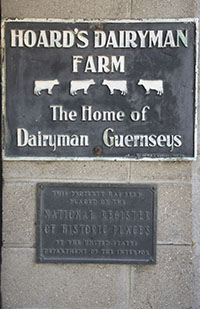

My daily commute takes me past the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm, located just north of town and less than two miles from our office. On this sunny morning, recently cut fourth crop hay laid in rows in the field in front of the farm, offering a fragrant welcome to anyone who drove past. That smell of fresh cut alfalfa immediately brought a sense of calm over me; it’s an aroma that most of us with agriculture roots love and appreciate.

That alfalfa will soon be harvested as haylage and stored in plastic bags on the farm. Eventually, the haylage will be used to feed the cows that call the Hoard’s Dairyman Farm home.

Crop experts in the Badger State in the late 1800s did not believe that alfalfa would survive the winter in this cold climate. Hoard was confident in this, though, and so he bought a farm, established a herd of cows, and proved that alfalfa could be grown in Wisconsin. It didn’t take long for others to follow suit, and today, alfalfa makes up a significant portion of dairy cattle rations across the country and around the world.

The Hoard’s Dairyman Farm has remained part of the W.D. Hoard and Sons Company ever since, evolving just as the dairy industry has. When I first visited the farm as a high school student attending the National 4-H Dairy Conference, they were milking in the original tie stall barn. I can remember the rows of Guernsey cows in the stalls and box stalls that filled the barn.

Age eventually caught up with the tie stall barn, and in 2007, a freestall barn and parlor were built to house the growing herd of registered Guernseys. The tie stall barn was retrofitted into a freestall barn, and for about 10 years, Jerseys were added to the herd and were housed in that facility.

Most recently, a freestall barn was built to house a majority of the milking herd and four voluntary milking systems, or robots. This is where most of the cows are milked today, while the rest of the herd is milked in the parlor.

Our farm is not a research farm or a demonstration farm; it is a working part of our company. By operating a farm alongside our magazines, we experience the important business decisions, ups and downs in milk price, and herd health issues that many of our readers face. And that is another reason why Hoard started the farm in the first place. He wanted the magazine’s staff to stay closely linked to the struggles and successes that come with dairy farming.

I am always thankful to work for a magazine that allows me to remain connected to production agriculture, and I appreciate the opportunity to have ties to a local dairy when I am away from my family’s farm. A few deep breaths of fresh cut alfalfa this morning was a great reminder of this.

The author is the senior associate editor and covers animal health, dairy housing and equipment, and nutrient management. She grew up on a dairy farm near Plymouth, Wis., and previously served as a University of Wisconsin agricultural extension agent. She received a master’s degree from North Carolina State University and a bachelor’s from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.