Through the blending of genetic principles learned in his extensive studies and judging concepts he perfected as a student and later as a coach, Robert Walton forever changed dairy cattle breeding.

Robert Walton's love of genetics was sparked long ago as a teenager, as he dreamed of ways to breed better cows through scientific principles. Along the way, he tapped into the collective know-how of leading geneticists and evaluators to glean their insight and test his ideas.

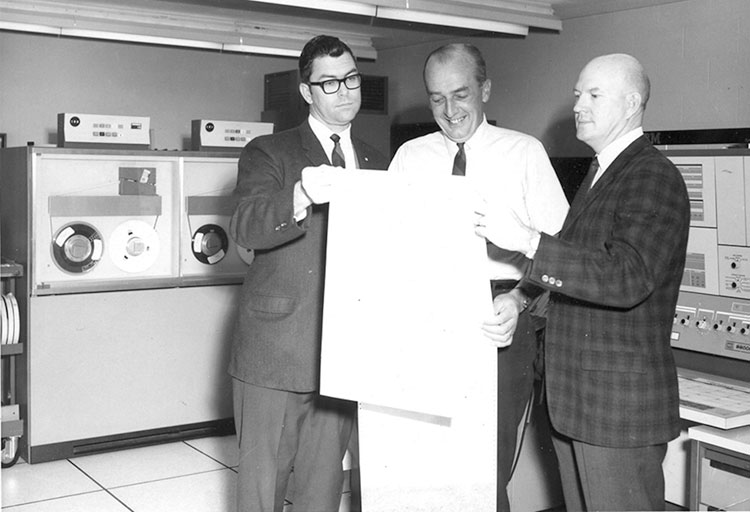

After a stint in academia, Walton moved on to American Breeders Service (ABS). Others in the organization quickly recognized Walton's talents, and he moved from head of the Holstein young sire program to marketing director and then president in a relatively short time span. At ABS, Walton developed the industry's first progeny testing program, designed sire evaluation programs later adopted by USDA, launched a mating program and perfected linear evaluation. In later years, he revamped the ABS marketing and distribution system.

Ever mindful of the greater world around him, he gave back through service at World Dairy Expo, National Dairy Shrine and the Holstein Foundation. Recently, we asked Bob to share some perspectives from his work and recollections as World Dairy Expo's longest serving director.

World Dairy Expo originally started as the World Food Expo. After two or three years, it was clear it wasn't going to get legs in that form. How did the current idea of World Dairy Expo take shape?

Discussions and energy were placed behind the World Food Expo concept in 1965 as the National Dairy Cattle Congress in Waterloo, Iowa, was experiencing difficulties. Norm Magnussen, Allan Hetts and Howard Voegeli, among other noted cattle breeders, played a key role in helping transition the show to Madison in the first place. Wisconsin breeders were very influential in raising money with a dairy calf sale to fund the initial show. Later on, the state of Wisconsin also injected some cash. However, despite these efforts, the World Food Expo never took off after its launch.

My first real involvement was in 1970. At that point, the show was just limping along because it was underfunded and not well-attended. The vision of having urban attendees never came about. That's when the industry came up with a new plan.

I give major credit to University of Wisconsin's Dean Glenn Pound as the key person putting the concept together through a stock sale. Bev Craig, a former Oscar Mayer executive, served as the executive director of the revamped show.

During this time, the AMPI Cooperative was a major contributor and purchased more shares than anybody else. However, various marketing co-ops, A.I organizations and other groups all bought in. Most organizations purchased one share at $5,000 each in May of 1970. After that sale, I began representing American Breeders Service on World Dairy Expo's board of directors. That same year, Chicago's long-running International Dairy Show closed its doors and events moved to World Dairy Expo. The board signed notes every year with the Bank of Sun Prairie to keep the place alive from one year to the next.

How have the two main cornerstones, the cattle show and trade show, helped one another grow and develop the event?

While World Dairy Expo was originally a cattle show, it quickly transitioned to include commercial exhibits. That was an important change in those early days. That was a different concept as compared to almost every other show around the country or even the world. The cattle show and commercial exhibits are like a good marriage, both need one another and make each other successful. The cattle show was a drawing card, but it would not have succeeded without commercial exhibits.

You've been all over the globe. How does World Dairy Expo compare to other shows?

There are magnificent shows throughout Europe. But the commercial part sets World Dairy Expo apart and makes it unique. Others have emulated the idea but none have really cultivated the commercial support from almost every continent.

The shows in Europe are supported much more by city attendance. Those shows also receive government support while World Dairy Expo is free standing with a little assistance from the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. The moral support from Wisconsin is more important than the dollars that they put into annual operations. That said, outlays in infrastructure such as buildings have been very important to the long-term growth.

After earning your doctorate in genetics, you joined the University of Kentucky as an assistant professor. During that time, the University of Kentucky won its first and only National Intercollegiate Dairy Cattle Judging Contest with you as the team's coach. How has dairy judging influenced your career?

At Oklahoma State, I was on the dairy judging team with Bob Basse, the son of a well-known Wisconsin Guernsey breeder. He was very knowledgeable about the dairy industry having grown up in Wisconsin. I remember the very first judging contest as a freshman like it was yesterday. I came in last, and Bob came in first. So I said to myself, "I better stick close to that tall, red-headed kid from Wisconsin, I might learn something."

The next year as sophomores at the university contest, I came in first and Bob Basse came in second, and we both made the judging team. We went to Fort Worth, our first collegiate contest, and Bob was first and I was second. At Kansas City, I was first and Bob was second. Bill Pickett was the third member of the team. We dominated those contests and beat everybody. But when we got to the national contest at Waterloo, we came in third, even though we were undefeated until that point. It wasn't our day.

In those days, you had to forget how much milk they gave; judging was another world. It was for fun, not for seriousness, at least in my opinion. Later in my career, I changed how cows were evaluated and helped make it much more relevant to breeding better cows.

After receiving my doctorate, Dwight Seath hired me to come to Kentucky in 1958 because he was leaving on a one-year Fulbright Scholarship. He was department head and dairy judging coach.

When I took over that team, it was coming off a 20th place finish at the national contest. I revamped our workouts and worked with the team for about six weeks. Then we traveled to the International Dairy Show in Chicago and won. Kentucky had never won anything up until that point. They didn't even have a trophy case.

The next year I started all over with a brand new team. We won the 1959 Waterloo contest. So, my first two teams won the International and National Collegiate contests, respectively.

I put those teams through extensive training. One practice technique I used at the Ohio State Fair included a quick sorting exercise. Even though there were big classes of 50 to 60 head, their job was to pick out the first four heifers or cows before the judge started making his first pull. An added part of the exercise involved memory retention. I would not tell them which classes they were going to give reasons on until the afternoon was over. That really tested them.

Even though we had a small dairy department at Kentucky, we did well. I don't think Wisconsin, Iowa State or Cornell ever beat one of my teams.

How did you employ your dairy cattle evaluation skills at ABS?

When I came to ABS, Mr. Prentice (the owner) had written a booklet called Utility is Beauty. What he wrote was actually right, but people didn't want to hear what he had to say about focusing on production and relegating type to only functional economically important traits. Most breeders were just mad at him.

Controversy ensued. Mr. Prentice told ABS not to classify bulls or show the score of any animal in an advertisement.

That policy was in place when I arrived at ABS. Because of my judging experience, I was able to convince the company president we needed to change policy. He spoke to Mr. Prentice, who then reversed that decision about type evaluation.

It was a wise move because our competitors were making hay on the issue, and we were just shooting ourselves in the foot.

How did you revamp sire selection?

First, I designed the ABS Progeny Testing program in 1962 that included 60,000 cows in 1,000 associated herds in all major dairy areas in the U.S. We sampled 200 young bulls each year using a randomized distribution of their semen into those herds.

Then I developed a special mating program to produce these young sires combining my judging and evaluating skills. I traveled all over the country evaluating the top daughters of the top bulls of every bull stud, utilizing DHIA production records for initial screening. With this system, I would walk into a breeder's herd whom I'd never met previously and ask to see a certain cow. Soon after implementing this approach, I could usually walk into the herd and pick that cow without the dairyman because I had learned the characteristics of such high-producing daughters of each sire.

The very best of this select group were then contracted to be bred to what I thought was the perfect bull for that cow from the inventory of semen I had accumulated from the best bulls in the breed.

That practice led to the Genetic Mating Service (GMS). My theory was, "If I could use the process and all the information in making those matings for these special cows, why can't we do that for every commercial cow in the country?" That also led to the Genetic Mating Service database, and as it progressed we also developed a linear evaluation system.

You developed the Estimated Daughter Superiority System, later adopted by USDA-AIPL as the Predicted Difference system. How did it come about?

My dream when I was 13 years old, when I learned a little about genetics, was to breed a herd of cattle that were homozyous cattle for all the good genes. Of course, that's not possible, but I didn't know any better as a teenager. That idea got me started studying genetics.

I took all the genetic courses I could at Oklahoma State. Then I was an exchange student in Sweden for a year, and my professor was Ivar Johansson, who got his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin about the same time as the highly regarded geneticist Dr. J.L. Lush.

Johansson was the leading geneticist in Europe at that time. Through Johansson, I got introduced to the concept of a new, more robust genetic evaluation system that he had learned from Lush. In later years, I learned more about it directly from Lush while getting my Ph.D.

The actual formulation that became predicted difference ($PD) at the USDA was first introduced at ABS as Estimated Daughter Superiority. I pulled the formula right out of my studies with Johansson.

I began putting this concept together while teaching at Kentucky. After awhile, I realized there was no way my students nor I could really do this thing right with our limited numbers. At the same time, however, I began testing some of the concepts at the Kentucky Artificial Breeders Association (KABA) as I advised them on bull-buying trips.

I kept developing the system; it was still a pipe dream of sorts. About that time, USDA published the first herd mate comparison report. It was not a formula, it was just raw data. A herd mate wasn't very well-defined. But they published it, and I got a copy in 1959. Incidentally, the funding for USDA to conduct the project came from J. Rockefeller Prentice who didn't want any credit. He just quietly wrote them a check for roughly $275,000 so they could contract the computer time to run it.

That herd mate comparison process began to put the pieces together for me because I thought we could refine this evaluation system way beyond this first step. Year's later, others, who were much more mathematically advanced than I, took it further. But I am the one who actually took the concept and put it into practice.

One final question. The long-standing ABS Coffee, Milk and Donut Run has been a staple each morning for World Dairy Expo dairy cattle exhibitors. Tell me how the idea came about?

That goes back to my days at Waterloo when I was an assistant on the show string with the Meadow Lodge Farm. Back in those days, you had your cot and slept in front of the cows. Maybe you had an old coffee pot, but there wasn't any place to go get a bite to eat. You worked half the morning before you ever ate. It was tough!

When we started World Dairy Expo, I thought about those days. How nice it would be if you could have a cup of coffee, a glass of milk and a donut in the morning when you're getting up and starting chores. That's why I started the ABS Coffee Run. Exhibitors really seem to have appreciated it over the years.

This article appears in the 2013 World Dairy Expo supplement on page EXPO 7.

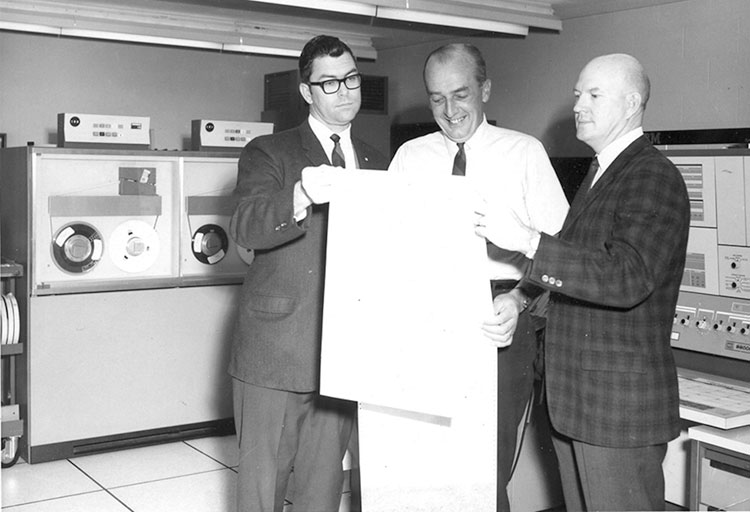

As World Dairy Expo's longest serving director, the show has always held a special place for Walton. Shown at the show are (L to R): Art Nesbitt of Nasco, Wisconsin Governor Lee Dreyfus, an aid to Governor Dreyfus and Robert Walton.

Robert Walton's love of genetics was sparked long ago as a teenager, as he dreamed of ways to breed better cows through scientific principles. Along the way, he tapped into the collective know-how of leading geneticists and evaluators to glean their insight and test his ideas.

After a stint in academia, Walton moved on to American Breeders Service (ABS). Others in the organization quickly recognized Walton's talents, and he moved from head of the Holstein young sire program to marketing director and then president in a relatively short time span. At ABS, Walton developed the industry's first progeny testing program, designed sire evaluation programs later adopted by USDA, launched a mating program and perfected linear evaluation. In later years, he revamped the ABS marketing and distribution system.

Ever mindful of the greater world around him, he gave back through service at World Dairy Expo, National Dairy Shrine and the Holstein Foundation. Recently, we asked Bob to share some perspectives from his work and recollections as World Dairy Expo's longest serving director.

World Dairy Expo originally started as the World Food Expo. After two or three years, it was clear it wasn't going to get legs in that form. How did the current idea of World Dairy Expo take shape?

Discussions and energy were placed behind the World Food Expo concept in 1965 as the National Dairy Cattle Congress in Waterloo, Iowa, was experiencing difficulties. Norm Magnussen, Allan Hetts and Howard Voegeli, among other noted cattle breeders, played a key role in helping transition the show to Madison in the first place. Wisconsin breeders were very influential in raising money with a dairy calf sale to fund the initial show. Later on, the state of Wisconsin also injected some cash. However, despite these efforts, the World Food Expo never took off after its launch.

My first real involvement was in 1970. At that point, the show was just limping along because it was underfunded and not well-attended. The vision of having urban attendees never came about. That's when the industry came up with a new plan.

I give major credit to University of Wisconsin's Dean Glenn Pound as the key person putting the concept together through a stock sale. Bev Craig, a former Oscar Mayer executive, served as the executive director of the revamped show.

During this time, the AMPI Cooperative was a major contributor and purchased more shares than anybody else. However, various marketing co-ops, A.I organizations and other groups all bought in. Most organizations purchased one share at $5,000 each in May of 1970. After that sale, I began representing American Breeders Service on World Dairy Expo's board of directors. That same year, Chicago's long-running International Dairy Show closed its doors and events moved to World Dairy Expo. The board signed notes every year with the Bank of Sun Prairie to keep the place alive from one year to the next.

How have the two main cornerstones, the cattle show and trade show, helped one another grow and develop the event?

While World Dairy Expo was originally a cattle show, it quickly transitioned to include commercial exhibits. That was an important change in those early days. That was a different concept as compared to almost every other show around the country or even the world. The cattle show and commercial exhibits are like a good marriage, both need one another and make each other successful. The cattle show was a drawing card, but it would not have succeeded without commercial exhibits.

You've been all over the globe. How does World Dairy Expo compare to other shows?

There are magnificent shows throughout Europe. But the commercial part sets World Dairy Expo apart and makes it unique. Others have emulated the idea but none have really cultivated the commercial support from almost every continent.

The shows in Europe are supported much more by city attendance. Those shows also receive government support while World Dairy Expo is free standing with a little assistance from the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. The moral support from Wisconsin is more important than the dollars that they put into annual operations. That said, outlays in infrastructure such as buildings have been very important to the long-term growth.

After earning your doctorate in genetics, you joined the University of Kentucky as an assistant professor. During that time, the University of Kentucky won its first and only National Intercollegiate Dairy Cattle Judging Contest with you as the team's coach. How has dairy judging influenced your career?

At Oklahoma State, I was on the dairy judging team with Bob Basse, the son of a well-known Wisconsin Guernsey breeder. He was very knowledgeable about the dairy industry having grown up in Wisconsin. I remember the very first judging contest as a freshman like it was yesterday. I came in last, and Bob came in first. So I said to myself, "I better stick close to that tall, red-headed kid from Wisconsin, I might learn something."

The next year as sophomores at the university contest, I came in first and Bob Basse came in second, and we both made the judging team. We went to Fort Worth, our first collegiate contest, and Bob was first and I was second. At Kansas City, I was first and Bob was second. Bill Pickett was the third member of the team. We dominated those contests and beat everybody. But when we got to the national contest at Waterloo, we came in third, even though we were undefeated until that point. It wasn't our day.

In those days, you had to forget how much milk they gave; judging was another world. It was for fun, not for seriousness, at least in my opinion. Later in my career, I changed how cows were evaluated and helped make it much more relevant to breeding better cows.

After receiving my doctorate, Dwight Seath hired me to come to Kentucky in 1958 because he was leaving on a one-year Fulbright Scholarship. He was department head and dairy judging coach.

When I took over that team, it was coming off a 20th place finish at the national contest. I revamped our workouts and worked with the team for about six weeks. Then we traveled to the International Dairy Show in Chicago and won. Kentucky had never won anything up until that point. They didn't even have a trophy case.

The next year I started all over with a brand new team. We won the 1959 Waterloo contest. So, my first two teams won the International and National Collegiate contests, respectively.

I put those teams through extensive training. One practice technique I used at the Ohio State Fair included a quick sorting exercise. Even though there were big classes of 50 to 60 head, their job was to pick out the first four heifers or cows before the judge started making his first pull. An added part of the exercise involved memory retention. I would not tell them which classes they were going to give reasons on until the afternoon was over. That really tested them.

Even though we had a small dairy department at Kentucky, we did well. I don't think Wisconsin, Iowa State or Cornell ever beat one of my teams.

How did you employ your dairy cattle evaluation skills at ABS?

When I came to ABS, Mr. Prentice (the owner) had written a booklet called Utility is Beauty. What he wrote was actually right, but people didn't want to hear what he had to say about focusing on production and relegating type to only functional economically important traits. Most breeders were just mad at him.

Controversy ensued. Mr. Prentice told ABS not to classify bulls or show the score of any animal in an advertisement.

That policy was in place when I arrived at ABS. Because of my judging experience, I was able to convince the company president we needed to change policy. He spoke to Mr. Prentice, who then reversed that decision about type evaluation.

It was a wise move because our competitors were making hay on the issue, and we were just shooting ourselves in the foot.

How did you revamp sire selection?

First, I designed the ABS Progeny Testing program in 1962 that included 60,000 cows in 1,000 associated herds in all major dairy areas in the U.S. We sampled 200 young bulls each year using a randomized distribution of their semen into those herds.

Then I developed a special mating program to produce these young sires combining my judging and evaluating skills. I traveled all over the country evaluating the top daughters of the top bulls of every bull stud, utilizing DHIA production records for initial screening. With this system, I would walk into a breeder's herd whom I'd never met previously and ask to see a certain cow. Soon after implementing this approach, I could usually walk into the herd and pick that cow without the dairyman because I had learned the characteristics of such high-producing daughters of each sire.

The very best of this select group were then contracted to be bred to what I thought was the perfect bull for that cow from the inventory of semen I had accumulated from the best bulls in the breed.

That practice led to the Genetic Mating Service (GMS). My theory was, "If I could use the process and all the information in making those matings for these special cows, why can't we do that for every commercial cow in the country?" That also led to the Genetic Mating Service database, and as it progressed we also developed a linear evaluation system.

You developed the Estimated Daughter Superiority System, later adopted by USDA-AIPL as the Predicted Difference system. How did it come about?

My dream when I was 13 years old, when I learned a little about genetics, was to breed a herd of cattle that were homozyous cattle for all the good genes. Of course, that's not possible, but I didn't know any better as a teenager. That idea got me started studying genetics.

I took all the genetic courses I could at Oklahoma State. Then I was an exchange student in Sweden for a year, and my professor was Ivar Johansson, who got his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin about the same time as the highly regarded geneticist Dr. J.L. Lush.

Johansson was the leading geneticist in Europe at that time. Through Johansson, I got introduced to the concept of a new, more robust genetic evaluation system that he had learned from Lush. In later years, I learned more about it directly from Lush while getting my Ph.D.

The actual formulation that became predicted difference ($PD) at the USDA was first introduced at ABS as Estimated Daughter Superiority. I pulled the formula right out of my studies with Johansson.

I began putting this concept together while teaching at Kentucky. After awhile, I realized there was no way my students nor I could really do this thing right with our limited numbers. At the same time, however, I began testing some of the concepts at the Kentucky Artificial Breeders Association (KABA) as I advised them on bull-buying trips.

I kept developing the system; it was still a pipe dream of sorts. About that time, USDA published the first herd mate comparison report. It was not a formula, it was just raw data. A herd mate wasn't very well-defined. But they published it, and I got a copy in 1959. Incidentally, the funding for USDA to conduct the project came from J. Rockefeller Prentice who didn't want any credit. He just quietly wrote them a check for roughly $275,000 so they could contract the computer time to run it.

That herd mate comparison process began to put the pieces together for me because I thought we could refine this evaluation system way beyond this first step. Year's later, others, who were much more mathematically advanced than I, took it further. But I am the one who actually took the concept and put it into practice.

One final question. The long-standing ABS Coffee, Milk and Donut Run has been a staple each morning for World Dairy Expo dairy cattle exhibitors. Tell me how the idea came about?

That goes back to my days at Waterloo when I was an assistant on the show string with the Meadow Lodge Farm. Back in those days, you had your cot and slept in front of the cows. Maybe you had an old coffee pot, but there wasn't any place to go get a bite to eat. You worked half the morning before you ever ate. It was tough!

When we started World Dairy Expo, I thought about those days. How nice it would be if you could have a cup of coffee, a glass of milk and a donut in the morning when you're getting up and starting chores. That's why I started the ABS Coffee Run. Exhibitors really seem to have appreciated it over the years.