With some milker encouragement, “Come on Mamas, out ya go,” the cows slowly sauntered out of the parlor stalls and gathered in the exit space. On the parlor deck lay a pile of fresh manure still steaming in the cool mid-winter air and highlighted in the bright sunlight beaming through the parlor window.

In an effort to maintain a clean working area and prevent tracking of the manure throughout the rest of the parlor, a milker grabbed a hose and sprayed the parlor deck to push the manure aside. As the stream of water hit the manure pile, a mist of water droplets and manure particles sprayed into the air and coated the just-released dairy cows that lingered in the exit way.

Do you ever wonder, “What’s in that mist? What affect does it have on cows?”

A volcano of germs

Research has proven that the average human sneeze can send approximately 100,000 germs into the air at speeds of up to 100 miles per hour. In the same vein, flushing the toilet can distribute thousands of microorganisms up to 2.7 feet into the air, creating a toilet plume.

With enough air or liquid force, we can convert a physical substance into small particles, light enough to be carried through the air. This is called aerosolization. There are folks that perform very involved and technical studies on these biological incidences that have resulted in better methods to contain sneezes and improved toilet design.

Aerosol and droplet-mediated transmission of bacteria is a real risk that can spread germs and create infections. The amount of bacteria in the water and manure mist, and the distance they are able to travel, depends on the volume and force of water, air currents, and size and number of bacteria present in the environment.

Mastitis-causing bacteria found in manure range in size from 0.5 to 2 micrometers (µm). Studies show that at this size, with turbulent air currents, bacteria may take up to 12 to 41 hours to settle over great distances.

Depending on the size of the water droplet they are attached to, settling times and distance may be shorter. As a droplet of water with bacteria hits a surface, the bacteria are pushed radially outward in all directions by the force of the water while also bumping into each other to further their stretch. When dispersed by water force and ventilation fans, a single droplet of water with bacteria may spread thousands of microbes over the surface of a teat.

I needed to know what was in that mist of water and manure. With culture plates held at approximate udder height, I stood among the cows and encouraged the milker to spray down the parlor deck. The cows, the culture plates, and yours truly were all coated with a fine mist of manure and water. Twenty-four hours later, examination of the culture plates showed a large collection of bacteria including E. coli and Klebsiella. Those two bacteria are major coliform mastitis pathogens.

But, what about applying teat dip?

Do postmilking teat dips protect animals from the spray?

To learn more, a device was designed to hold an open agar plate and milking unit inflation plugs to represent teats. Three of the plugs were dipped with a commercial 1 percent iodine teat dip. One of the plugs was not dipped. An open culture plate was attached to capture coliform bacteria in the air.

Collecting farm data

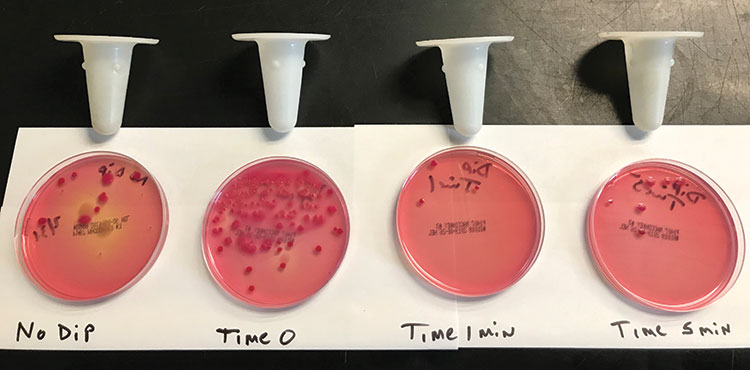

A garden-style parlor hose was used to spray water at approximately a 45-degree angle at 40 to 60 pounds per square inch (psi) to remove manure from the parlor deck. Sterile swabs were used to remove water and manure overspray from the nondipped plug and dipped plugs immediately after spraying and at 1 minute and 5 minutes after spraying. Blood agar and MacConkey agar culture plates were immediately inoculated with the swabs and incubated for 24 hours.

Evaluation of the plates revealed many environmental mastitis-causing pathogens including various environmental Streptococcus species and coliform bacteria. The number of bacteria present was reduced over time but, even after five minutes of the manure and water droplets in contact with the teat-dipped plug, bacteria were present.

After milking, the most important job is to prepare animals for whatever they encounter until the next milking. This includes preventing bacterial colonization on teat ends. Postmilking teat dips are designed to flush milk residue off of teats, while conditioning teat skin and protecting animals from bacteria they might find in the environment. This all takes place so that teat ends are given time to close after milking. Just like milk film, manure is a great food source, and when left on teat ends, bacteria thrive.

Most teat dips are capable of up to a five log reduction in bacteria load on teat ends; however, their abilities are diminished in the presence of organic matter such as manure and water droplet splatter. Organic matter and manure interfere with the antimicrobial activity of sanitizing compounds by degrading the killing abilities of the chemicals in the active germicide or by protecting microorganisms from the sanitizer by creating a physical barrier.

A better cleaning method

Options to keeping a clean parlor:

- Remove animals from the area when spraying milking units or the milking area.

- When animals are present, use a shovel or other device to push manure out of the way.

- Ensure all surfaces of all teats are coated with teat dip after milking.

- Turn off ventilation fans when washing the parlor to allow aerosolized bacteria to settle more rapidly.

Prevent disease, too

In addition to mastitis-causing pathogens, there are many bacteria, viruses, and parasites found in manure. If aerosolized, these microorganisms can easily cause disease in dairy animals.

It must be noted that flushing the toilet has not yet been scientifically linked to spread of disease or infections in people, nor has spraying the parlor deck with water been directly linked to animal diseases. But these are risk factors that we should be aware of . . . and maybe we should close the lid when flushing.