Don’t underestimate the impact that government purchases are having on the dairy market. From 2015 to 2018, USDA purchases of dairy products for various domestic feeding programs such as school lunch programs averaged about $361 million per year. That stepped up to $495 million in 2019 largely due to “trade mitigation” purchases made to help offset the negative impacts of the various trade disputes. In 2020, we will likely see the government purchase about $1.5 billion worth of dairy commodities, three times as much as 2019.

This is a significant change from the recent trend in dairy market policy. From roughly 1933 to 2009, U.S. government policy tried to support farm level incomes by supporting market prices. But in 2009 the industry, and government, recognized that the price level the government was willing to support was simply too low to be of much value to U.S. dairy farmers. The government price floors also distorted markets and led to massive government-held inventories that overhand market prices for months (and years) after the initial collapse in prices.

Instead of trying to directly support market prices, new programs were devised to help protect farmers against a drop in their margin or revenue. First, we had the Margin Protection Program (MPP), which eventually morphed into the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program. Then Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) program was added to the portfolio. All of these programs are “insurance-like,” allowing farmers to protect margins or revenue directly, instead of trying to support market prices. By directly supporting farmers, they reduce market distortions, but government policy in the past two years seems to have shifted back toward direct purchases as well as these insurance programs.

What’s so bad about market distortions?

It doesn’t seem like such a bad thing for dairy farmers when the government is helping to push cheese prices to record highs. Most of the money spent has been directed toward cheese (and fluid milk). That has pushed cheese prices up about 170% from their pandemic-induced lows, while butter is only up 55% and nonfat dry milk is only up 25%.

From a short-term perspective, the rapid rise in cheese prices has resulted in amazingly large negative PPDs (deductions) from farmer’s milk checks. But from a longer-term perspective, I can see at least a few problems that will result from the government purchases.

Two problems

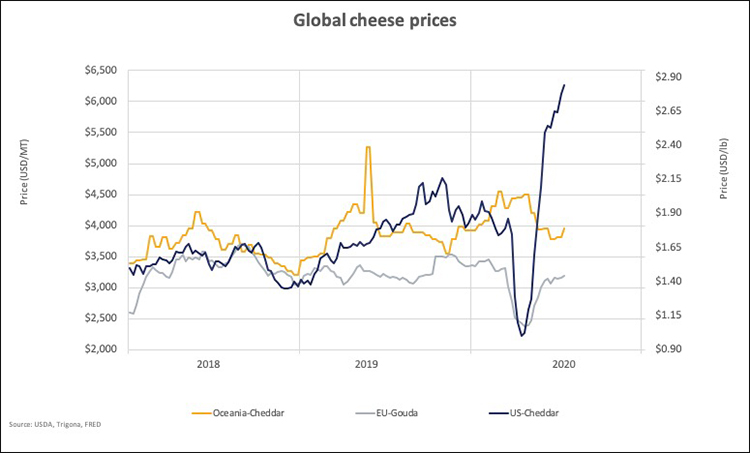

The first problem is that the government purchases have pushed U.S. cheese prices well above the world market. Who is going to want to import U.S. cheese at $2.90 per pound when they can buy it from Europe for $1.50 or New Zealand for $1.80?

At best, the U.S. government is buying 35 million to 40 million pounds of cheese per month through the various pools of money (Trade Mitigation, Section 32, CARES Act, Food Box) it has at its disposal. Year-to-date U.S. cheese exports have averaged 69 million pounds per month. Even with U.S. prices at a massive premium, U.S. cheese exports won’t drop to zero, but we are effectively trading short-term sales to the government for longer-term export sales. These pools of government money are eventually going to run dry, and there is a possibility that we will lose more in export sales than we gained in government purchases.

The second problem is that the government purchases are masking the true demand situation. The government is currently buying somewhere between 2% and 4% of total milk production in June, July, August, and possibly into September and October. Even with retail sales running above last year and food service sales improving, I’m still estimating commercial demand is going to be down 1% to 2% this summer. That means the government purchases are going to more than make up for the decline in commercial purchases.

If the pandemic was going to come to an end soon, the purchases would have worked as an effective bridge to get us across a short period of disrupted commercial activity. But I’m afraid the pandemic is not coming to an end anytime soon and domestic commercial demand is going to stay below year-ago levels. With cheese exports expected to slow as well, we’re looking at a poor demand scenario when the government purchases stop.

Long-term sales

I don’t want to be overly pessimistic. There have been some beneficial consumption shifts. With sales up significantly at the pizza chains and fast-food drive-thru windows busy, we think each meal served through food service now has more dairy in it than before COVID-19. Retail sales of dairy products are still above last year and maybe some of the at-home consumption shifts are going to stick with us for the long-run. But much of the strength we’ve seen in the dairy markets has been driven by large U.S. government purchases of milk and dairy products. I’m worried that the purchases will slow significantly before commercial demand has fully recovered and it sets us up for another drop in milk prices.