U.S. and global dairy markets have been bizarre this year. Looking at the block cheddar cheese market on the CME confirms that story. We went from $2 per pound prior to the pandemic and then sank to a 20-year low of $1 per pound by late April. Markets then rebounded to an all-time high of $3 per pound in July. This cheese market activity all happened in a span of 118 sessions. And since then, the market dropped down toward $1.50 and rocketed back up to $2.50-plus in early October trading on the CME.

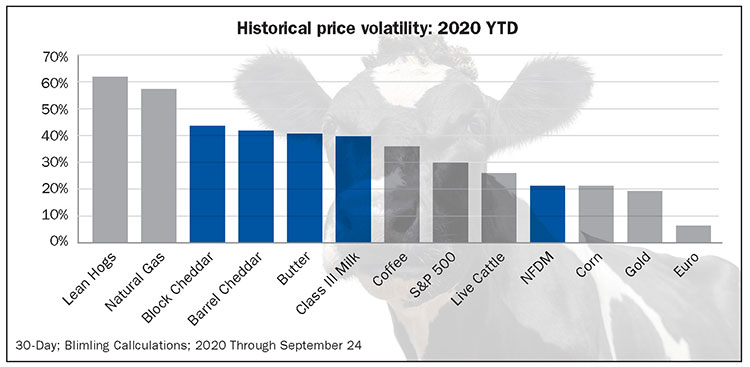

When you look at the statistical measures of volatility, dairy markets in 2020 have been among the most volatile commodities in the world. Lean hogs and natural gas have seen the most. Right next to that trio is dairy . . . specifically, block and barrel Cheddar, butter, and Class III milk. Indeed, dairy markets have been more volatile than coffee, corn, cattle, gold, and even the stock market. There’s no assurance that these volatile markets are done.

When we think about these record cheese prices, it’s important to note that $24 milk has not universally translated to $24 milk checks for all dairy producers. Yes, in July, we had a $24.54 Class III price, the second-highest ever. However, the Class IV price for the month was $13.76. When those prices get blended out through the federal milk marketing orders, dairy farmers in most regions did not see anything close to $24.

Protecting milk checks

The Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) program, a new product in the past couple years under the federal crop insurance umbrella, has drawn substantial interest. In 2020, producers enrolled about 55 billion pounds of milk, representing nearly 25% of U.S. milk production. Those dairy farmers who had coverage in place for the second quarter of 2020 realized significant payouts due to the low prices that we endured at the time.

Likewise, dairy farmers who enrolled in Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) also received some risk management help, and dairy producers acquired Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP) payments from the government. When we look at overall farm margins for 2020, which include milk revenue, DRP, DMC, and payments from the two rounds of the CFAP, this year will turn out to be a pretty good year for many dairy farmers.

Looking to the new year

Our forecast for 2020 growth in milk production is 1.4%, and we have 2021 forecasted at plus 1.5%. But here is the big question for 2021: We’ve seen a lot of cooperatives and milk handlers roll out various supply control programs over the course of 2020. Dairy farmers are being held to base programs or various schemes designed to slow milk output. While our model says growth of 1.5% for 2021, we may need to talk that number down a little bit based on some of these supply mitigation programs.

Let’s consider demand-side issues. One of the main concerns is a shakeup in school milk. As it stands, about 60% of kindergarten through twelfth grade students are starting school virtually. Schools have been ordering less milk and other dairy products. The numbers are fairly substantial.

We’ve seen estimates that say that 7% to 8% of fluid milk consumption flows to school milk programs. When you do the math, that’s about 86 million pounds of milk per week based on a 40-week school year. If we’re running at 50% of normal, which might be a generous assessment, that equals enough milk to make 90 extra truckloads of milk powder per week or close to 100 extra truckloads of cheese.

Clearly, we have more at-home meal occasions. A recent poll shows that 44% of Americans are eating breakfast at home every day, up from 33% before the pandemic. As for dinner, 33% are eating at home, up from 21%.

How has it played out in the restaurant versus grocery space? In March, we saw grocery store spending jump 31%, while food service spending fell 28%. By April, the food service industry got wiped out, down 55%, while grocery was plus 19%. That gap narrowed in subsequent months. By August, food service was down only 12%, while grocery stores were up 8%.

Dairy product inventories vary

When we look at specific dairy products, cheese stocks seem adequate at least for now, but it has been a very bizarre inventory-building season. In a typical year, the dairy sector builds inventories from January into July and then we start drawing down for the rest of the year. This year, inventories peaked in April with a huge influx of cheese and stocks have been going down ever since that moment. All in all, cheese stocks seem adequate, but we’ve seen some really erratic flow.

Last year at this time, the 2020 futures were trading at $1.77, two years ago (for 2019) it was at $1.67, and today we are looking at $1.76 for 2021 on All-Cheese basis. That compares to a trailing five-year average of $1.64 per pound. It’s going to be very difficult for cheese buyers to put together budgets, and that’s even before contemplating the immense spread between block and barrel Cheddar cheese prices. I would be surprised if cheese buyers are putting anything less than $1.85, $1.90, or maybe $2 in their budgets if they are buying on a block basis for next year. With that number in mind, customers are then figuring out how to diminish that risk.

Let’s turn to butter. We’ve seen a pretty dramatic trend reversal in butter. The market is hanging out at about $1.50 per pound. When you look at previous Septembers, it’s been four years since the market has been below $2. The last time that we had an average near $1.50 was even longer ago in 2013.

That creates a strange new world for buyers, where $2 has become the norm, and now all of a sudden, we are seeing $1.50 per pound. This situation is really complicating the butter budget discussion for next year. Right now, the futures are averaging $1.85. The trailing five-year average is $2.20.

One of the reasons that butter has been relatively cheap is that we’ve got plenty in storage. If you look at August stocks, we were up 22% versus year prior levels.

How is that happening? We’ve heard that retail demand is great, right? Well, retail demand is great. In the month of September, we’re running about 30% above year-prior levels. People are baking and cooking more at home. However, the volume of butter we are eating at home is not enough to offset the loss of butterfat sales via food service.

Turning to the powder markets, the U.S. nonfat dry milk market climbed above $1 to over $1.10 for the first time in a while. World pricing has been even higher. There is pretty good demand in China and Asia. It’s not clear whether the demand is deep or durable, though.

The 2020 outlook

We’ve been forecasting and reforecasting again and again. The bottom line is that we’re not bullish. When we look at 2021, we forecast cheese prices at about $1.60 per pound, whey at 40 cents, butter at roughly $1.60, and milk powder at about $1.50. Given those product prices, Class III milk would net about $15.50 and Class IV could average $14.50. One reason our view is sort of bearish because we see milk supply being reasonably resilient.

But the bigger reason for bearish concern centers on demand-side issues. These are considerations one must keep in mind . . . 1% growth in cheese demand, 1% growth in butter demand, and flatlined fluid milk sales. When you look at exports, those sales are not really flowing heavy. Then consider that global economic growth is still constrained as a function of pandemic. We’re just not really confident that demand is going to be strong enough to carry the day, certainly early next year, from a dairy market perspective.

We could be wrong, and we could have to reforecast again. Things have been changing quite quickly throughout this pandemic economy. But we are really keenly focused on demand weakness, or at least a lack of demand strength, as being a key driver of the price action going forward.