“It's time for the dairy industry to take action,” emphasized Gerard Cramer, D.V.M., of the University of Minnesota.

Cramer was describing a new initiative to address lameness – a condition that affects about 50% of dairy cows during their productive life and results in economic losses, health concerns, and suboptimal animal welfare.

The University of Minnesota and the Council on Dairy Cattle Breeding (CDCB) are leading a project that brings together dairy farms, hoof trimmers, technology developers and many others to objectively identify lame cows, develop a data pipeline and use that data to make on-farm decisions, document change and develop genetic evaluations.

“Finding lame cows is the biggest thing the industry can do right now,” stated Cramer. “This initiative should help put some energy around that.”

“It’s a step we're taking with all the stakeholders – whether the hoof trimmers, veterinarians, genetic companies, CDCB, camera technology companies – to try to drive change and test theories out in the real world.”

Is there a genetic solution for lameness?

Cramer was among five presenters at the seventh annual CDCB Industry meeting held virtually on October 20, focusing on cow mobility and attracting 335 individuals from 26 countries.

At CDCB, we’ve been interested in genetic solutions for lameness for some time. In April 2018, CDCB introduced genetic evaluations for six health conditions – displaced abomasum, hypocalcemia, ketosis, mastitis, metritis, and retained placenta.

“Probably the most frequent question that I have received since then is: Why do we not have an evaluation for lameness?” stated Kristen Parker Gaddis, CDCB geneticist.

When Gaddis and other geneticists assessed the lameness records in our current U.S. data system, the lameness data was inconsistently documented and resulted in very low heritabilities. A genetic evaluation for lameness will not be effective until we deploy a more accurate way to record lameness and bring that data into our national cooperator database of dairy phenotypes (performance records) and genotypes.

We need an integrated framework

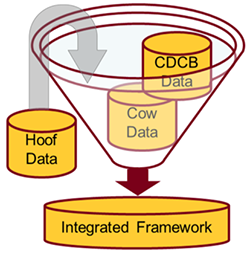

Cramer described an integrated framework where hoof health data resides on the farm and is pushed in different directions under control of the farm owner or herd manager. That lameness data can create action lists for farm personnel, hoof trimmers, or veterinarians. Data could go to auditors or milk buyers as requested. It can also go with other health data into the national database for genetic evaluations.

“The key to creating long-lasting change is to develop an integrated framework that combines lameness, genetic and farm data,” said Cramer. “This type of data structure already exists for records like production and somatic cell. Currently, however, the lameness or hoof lesion data is sitting outside this funnel.”

This integrated framework functions as a two-way pipeline with data available in the farm management software to make farm-level decisions.

In addition to farm management decisions and future genetic evaluations, Cramer views the integrated data as key to providing transparency and increasing dairy sustainability. He cites that the National Milk Producers Federation’s FARM (Farmers Assuring Responsible Management) program has set a standard of less than 5% severely lame cows as acceptable.

“I think in time those standards are going to change and probably get tighter. We need to be ready and prepared. Let's have appropriate data and be driving that data for the industry,” concluded Cramer.

How do we build this data pipeline?

Through the CDCB-University of Minnesota project, hoof health data will be collected by hoof trimmers and farm managers trained by a University of Minnesota team. Lameness data will also be captured on participating farms using a video analytic platform (VAP) that analyzes digital locomotion images and assigns lameness scores.

Approximately 1,100 hoof trimmers provide preventive and therapeutic care for approximately 9.3 million dairy cows in the U.S. Based on USDA estimates that 64% of cows undergo 1.5 regular preventive trimmings per year, there could be about 9 million preventive hoof trim sessions each year.

Based on these figures, there is a realistic opportunity to collect enough hoof health records, or phenotypes, to result in higher heritability and enable prediction models to allow producers to genetically select for dairy cows that can better resist hoof and mobility problems.

The opportunity to improve lameness is quite exciting and will make an impact for dairy farm economics, cow health, and animal welfare. With automation and new technologies, we can use objective and frequent data to help producers reduce the prevalence of lameness quite quickly, by detecting early and reducing the duration of lameness. When we add genetic evaluations for lameness conditions, we have the long-term potential to breed cows that are less likely to get lame.

Learn more

Click here to view presentations from Cramer and others at the October 20 CDCB meeting.

To participate in the lesion-related lameness study at UMN, click here or email umnhoofhealth@umn.edu.