Our customers are asking more and more questions about recession and the potential impact on dairy prices. We all remember what happened with dairy prices in 2009; it was a pretty incredible fall from record highs down to government-supported levels. With growing concerns that the U.S. (and maybe the world) is headed for another recession, it’s time to look at the connection between economic growth and commodity prices. But first, let’s dig into what a recession is and some of the numbers behind the U.S. economy.

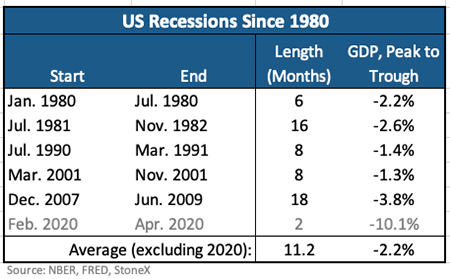

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), there have been six recessions since January 1980, with the last one being the lockdown COVID-19-induced two-month recession in 2020. I’ve left that one out of the averages since it is such an outlier . . . and hopefully won’t be seen again for a long time.

The average recession since 1980 has lasted 11.2 months with a 2.2% average decline in GDP from the peak. The “Great Recession” from 2008 to 2009 lasted 16 months and GDP fell by 3.8%.

So, when we think about the collapse in dairy prices that we saw in 2009, it’s important to remember that the Great Recession had a 50% longer duration than average and the decline in output was 73% bigger than average.

Are we likely headed into a 2008 to 2009 type recession?

Probably not.

Given the large savings consumers are sitting on, the tighter regulations around banks, and the tight labor market, there are reasons to think a recession right now might be a little less painful than average.

In a typical recession, layoffs are more frequent, employers slow new hiring, wages begin to flatline, and asset values dip. Consumers become more cautious, either out of necessity . . . they’ve lost their job . . . or they are concerned about losing their jobs or their wealth.

John Lancaster in our StoneX Dublin office throws in a third reason that I think is best described as “group think.” He thinks that even people who are in secure jobs with guaranteed pensions, such as civil servants and public sector workers, rein in their spending a bit during economic downturns, too. They see the continuous stream of negative news stories about the economy and reports about others cutting back on spending, so they start to question and even reduce their own spending and boost their saving rates as well.

Impact on prices

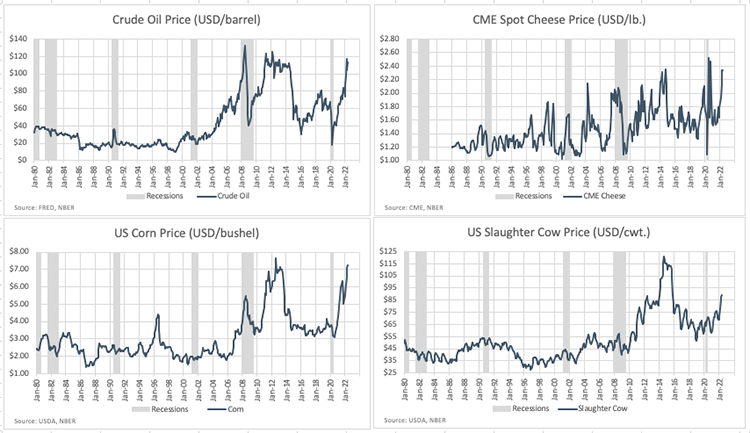

The change in consumer behavior shifts the demand curve for normal goods to the left. If there is no change in supply, it means prices should move lower. Below are prices for select commodities over the past 40 years. Surprisingly, average prices during a recession were higher than the preceding 12 months 53% of the time . . . I’m excluding 2020 again. But prices during the second half of a recession were almost always lower than prices during the first half of the recession. I think the reason prices in the second half of a recession are lower than the first half is that it probably takes some time for consumers to adjust their demand, and then it takes time for that weaker demand to be transmitted back to commodity prices.

There is an argument out there that any recession is likely to be mild and the impact on employment might be less than usual. Given how tight the labor market is, employers might just pull their job postings and stop hiring without making large cuts to their existing labor force. So, the demand impact from changes in employment and income might be pretty mild.

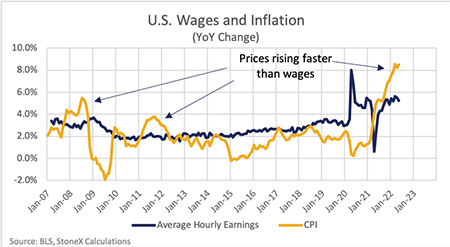

But even with the unemployment rate currently very low, we are already seeing consumers pulling back. Consumer prices have been rising faster than hourly wages for more than a year, and consumers are feeling it.

We’ve seen prices rising faster than wages a few times in recent history, namely 2008 and 2011. U.S. domestic cheese disappearance was weak in both of those years, but butter disappearance was strong, so I’m not sure we can make any generalized comments about dairy demand under these inflationary circumstances.

Bottom line

Whether we slip into an actual recession or not, consumers are feeling economically stressed by the higher prices and that is causing demand to slow, especially for lower-end goods and services. Personally, I think we’re headed for a mild recession.

If you wanted to make a bearish argument for dairy prices, I think you can argue that the U.S. dairy herd is recovering, and production will be improving at the same time that consumer demand is slowing. Feed costs are still high, but they typically fall during a recession so we could get a 5% to 10% drop in feed costs, and we could see dairy prices drop 10% to 30%.

The drop in commodity prices typically comes during the second half of a recession. It isn’t clear whether we’re technically in a recession in the U.S. or not, so any broad drops in commodity prices due to recession may still be months into the future.