The author is a professor emeritus at Virginia Tech and an independent dairy consultant with Down Home Heifer Solutions.

I always knew what the students in my dairy nutrition class were thinking when the response to a question was: “It depends!” Most of us know that for every decision we make on the dairy, there are costs and benefits. Effective managers are great at estimating the likelihood of a positive net benefit given the resources on their farm.

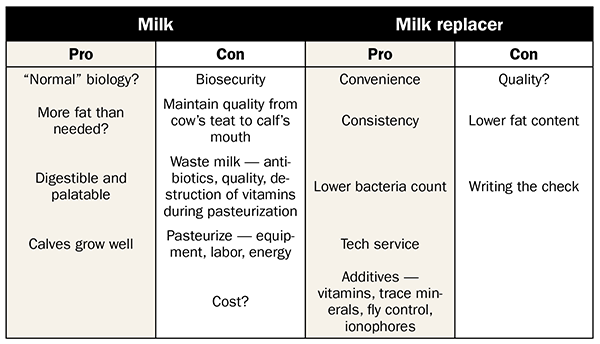

When it comes to calves, excellent health and growth performance can be achieved with either milk or a high-quality milk replacer. The table illustrates some of the perceived pros and cons of each alternative, and this article will dig deeper into the two options.

Straight from the source

When is milk the “best” choice for a dairy?

Since it comes from the cow’s teat, it’s hard to beat milk for palatability, digestibility, and nutrient content. On a “powder” basis, milk has about 26% protein and 30% fat, which is more than most milk replacers. When feeding more than 2 pounds of solids per day, calves will fatten up, which is a good thing for the young animals as it provides an energy reserve for extremes in weather or onset of illness.

Although fat and protein are often higher, milk, especially when it’s pasteurized, can be deficient in some vitamins and other nutrients. Fortunately, the calf is born with some body reserves of these nutrients — if the dry cow feeding program is excellent.

What is the “down” side of milk? Maintaining quality from the cow’s teat to the calf’s mouth is a challenge requiring timely cooling and excellent sanitation of all milk contact surfaces. If the farm has some endemic health issues such as Johne’s or bovine viral diarrhea (BVD), the use of an on-farm pasteurizer is highly recommended to address this issue and reduce bacterial growth in the milk. Maintenance of exceptional sanitation is of paramount importance, even if the pasteurizer is used. The farm must be fully aware of the initial and operating cost associated with use of a pasteurizer.

Is “waste” milk part of the diet? First, the dairy should not have sufficient waste milk to meet the needs of the calf program. If so, the health programs of the lactating herd need to be addressed.

Antibiotic residues in milk from treated cows are also a major concern. This is an issue when considering development of antibiotic resistance and the perception by our consumers of feeding “waste” milk to calves.

Based upon our studies with farms using waste milk, one needs to have a plan for supplementation with either saleable milk or milk replacer. The supply of waste milk in one study on a 1,000-cow dairy varied from 100 to 800 pounds per day. Also remember that waste milk is not “free.” It costs money to produce, and the goal of the farm should be to minimize the amount of waste milk produced.

For greatest success in the use of milk for calves, strict adherence to operating protocols is necessary and routine samples need to be obtained to measure total solids and the success (or failure) of the on farm pasteurizer. The farm must understand that there is a significant risk in transmitting disease and in bacterial overgrowth if the system is not intensively managed!

The power of powder

When are milk replacers the best choice for a farm?

As with whole milk, there’s a substantial difference in the quality of milk replacers. Some manufacturers utilize human edible grade ingredients and others have the goal of producing a low-cost product.

It is challenging to identify high quality simply by looking at the feed tag. Generally, the better replacers will be transparent about ingredient sourcing. They also offer support by field technical experts and research on their experimental farms or field work with dairies.

There can be a substantial difference in digestibility, mixing, and palatability of milk replacers. When vegetable ingredients are utilized, request research supporting their inclusion in the milk replacer for all ages of preweaned calves.

Why should a farm consider the use of milk replacers rather than milk?

Let’s assume a high-quality milk replacer is used. Consistency in nutrient content and convenience are significant advantages. We will also assume that we accurately measure the water and powder and have good mixing.

Milk replacers start with much lower bacteria counts. While the standard for bacteria count of pasteurized milk for calves is less than 20,000 cfu/mL, it would be extremely rare to observe counts above this with powder, even with less-than-optimal sanitation.

Mixing powder and water is quick, although it is highly recommended to have a mixing tank and use scales to accurately weigh water and powder to provide a consistent solids level. In addition, there’s no waiting for the pasteurizer and cooling milk to feeding temperature. Most milk replacers will have some additives, such as anticoccidial products, ionophores, fly control, or supplemental vitamins.

In nearly all cases, milk replacers will have less fat than milk, which means lower energy intake and less fattening. The lower fat levels might encourage earlier starter intake but at the expense of less fattening of the very young calf. Virginia Tech studies found that 5-week-old Jersey calves fed milk had roughly twice the level of body fat (9% versus 4%) as calves fed a low-fat milk replacer. The benefits of added fat are debatable, but logic would indicate some benefit to the youngest calves that have not begun to consume much starter.

One of the biggest downsides of milk replacer feeding is writing that check! However, if milk is the choice for feeding calves, the farm needs to charge the calf enterprise for this resource to make an effective economic decision.

Which is best?

Several years ago, we conducted a trial at Virginia Tech with 63 Holstein, Jersey, and crossbred calves fed either milk or a 28% crude protein, 20% fat milk replacer. The diets were formulated to provide equal pounds of total solids per calf per day. One treatment was milk replacer, the second was milk replacer for four weeks followed by four weeks of whole milk, and the third treatment was the opposite where calves started on whole milk and then transitioned to milk replacer.

What treatment yielded the best result? Average daily gain for each period and the number of health events were the same. The message is that, when properly managed, each source of nutrients can provide desirable performance.

What will work best in your situation? Either one can be successful and promote good health for the calf. Carefully consider how each system fits within the physical and personnel resources of your farm to determine which milk source will provide consistently good performance.