Over the past 12 months, 18.2% of U.S. dairy exports have gone to China. The world’s most populated nation is the second-largest destination for U.S. dairy after Mexico, which absorbed about 22.8% of exports. Even though our neighbor to the south is America’s largest dairy customer, globally, China is the largest dairy importer by a big margin. They aren’t the only driver of global dairy demand, but they are a very big driver, and that means they have a significant impact on U.S. dairy prices.

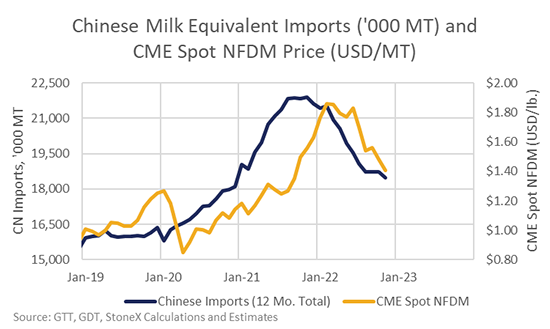

Over the past 12 months, Chinese imports have been trending lower. In fact, imports were down about 15% from last year in October. The downtrend for China’s imports lines up well with the decline in U.S. nonfat dry milk (NFDM) prices and with the general downtrend in U.S. dairy prices this year. The weaker Chinese imports have been driven by a combination of poor consumer demand in the face of sporadic COVID-19 lockdowns and growing domestic milk production that has displaced some imported dairy products.

The Chinese government made dramatic changes to its COVID-19 policies in late November and early December. The Chinese government previously had a policy of “dynamic zero-COVID-19” where they have been trying to identify and isolate all COVID-19 cases. As recently as mid-November, many places within the country required a negative COVID-19 test from the past 48 to 72 hours to get into stores, restaurants, trains, and other public places.

That meant everyone was constantly being tested for COVID-19 and new cases would be detected quickly. If you tested positive, there was a good chance you would be required to quarantine at a government-run facility until you tested negative. Your close contacts might also be required to report to the quarantine facility. If other positive cases were found in your apartment complex, the entire building or potentially the neighborhood could be locked down for 10 or more days. It was harsh, but that was the level of containment they felt was needed to keep the more contagious omicron variant from getting a foothold.

Obviously, the COVID-19 controls have had a significant and negative impact on economic activity, mental health, and consumer confidence in the country, and the government faced protests over the dynamic zero-COVID-19 policies in late November. Surprisingly, the government changed course in December and removed most of the restrictive policies. They have gone from a policy of limiting the spread of COVID-19 at nearly any cost to a policy that does almost nothing to stop the spread. (Note: Chinese officials are still requiring negative tests to visit nursing homes and hospitals.) It has been a surprising and dramatic shift in government policy.

Short term, this reversal is not helping dairy demand. Since people don’t need to get tested anymore, government testing stations have been closing up and the official tally of COVID-19 cases has been trending down. But it is clear that COVID-19 cases have exploded, particularly in Beijing. Our head of Asia Dairy, YiFan Li, has been in China for the past month and shared pictures of downtown Beijing, where the streets are empty. People are free to move around, but they are either sick or scared of getting sick, and they are choosing to limit contact. However, that doesn’t seem to be doing much to slow the spread.

The Chinese New Year starts on January 22. Many people either haven’t been able to travel or have been reluctant to travel over the past three years. Even though people are concerned about catching COVID-19, there seems to be a building wave of interest in traveling to see family over the New Year’s celebration. That will help spread the virus to all corners of the country, which is particularly concerning given the underdeveloped medical services in rural parts of China.

The next two to three months could be very rough for China. The eventual spread of COVID-19 through the population was inevitable, but they could have done more to prepare and protect those who are most vulnerable. Dairy demand is expected to stay on the weak side, and imports likely will, too. But when we get on the other side of this COVID-19 outbreak, there could be good pent-up demand like we saw in the U.S. and Europe after our economies opened back up again. That gives us some optimism for stronger Chinese demand (and higher dairy prices) during the second half of 2023.