We often talk about how dairy prices are going to raise or lower milk production, but we don’t spend much time talking about the impact that prices have on the demand side. One clear spot where we can see the impact of price changes on demand is the world market. I’ve spent a lot of time in the past three months writing about China and shifts in consumption and production that are happening there, but what about the rest of the world?

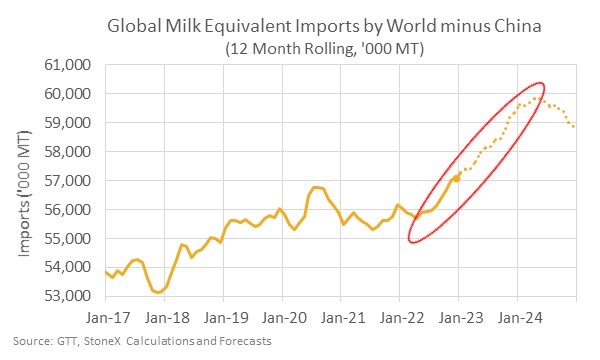

During the second half of 2022, milk equivalent imports by all countries other than China were running 1% to 2.5% above a year ago. There is a nice upward trend developing that has pushed imports slightly past their mid-2020 record peak. What’s even more impressive is that my demand models say these imports are going to continue to grow through 2023.

I will admit that the forecast looks optimistic. Imports by everyone other than China have been relatively flat over the past five years, so can we really see that much in-demand growth by international customers?

Our demand models are primarily driven by income, population, and dairy prices. Population growth is the steadiest component and there isn’t much to talk about there. While we are facing some economic headwinds, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has recently raised their gross domestic product (GDP) forecasts for many countries, and they are expecting GDP growth in developing countries to accelerate from 3.9% in 2022 to 4% in 2023. So, economic growth doesn’t look too bad in many of these importing countries. Then, we look at dairy prices, which are down 20% to 50% from their highs in April and May of last year.

The price and demand trade-off

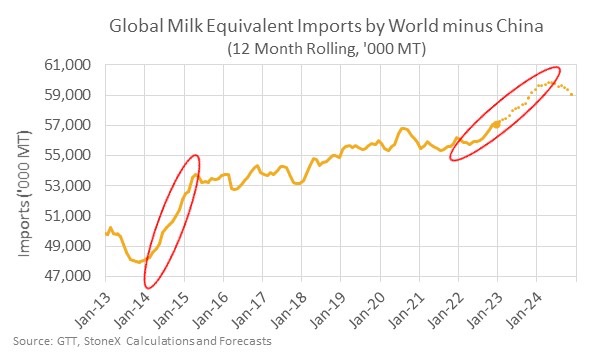

In very rough numbers, every 10% change in annual prices drives about a 1% change in global import demand in my models. So, when you start thinking about how far prices have fallen and how sensitive import demand is to prices, the import forecast starts to make some sense. But still, it looks aggressive, unless you zoom out and look at how import demand has reacted when prices have fallen in the past.

If we look at 2014, when we also saw a large and sustained decline in dairy prices, import volume surged higher. The gain in those days was even more aggressive than what I’m forecasting for 2023, although GDP growth was stronger back in 2014. In this light, the import forecast for 2023 looks completely reasonable.

I don’t want to get overly optimistic about demand, though. There are still concerns about Chinese import demand given the country’s strong domestic milk production. We’re still facing headwinds in the U.S. market too, particularly on butter. But we’ve already seen some improvement in demand outside of China and we could see that demand continue to grow through 2023, partly thanks to the lower price levels.