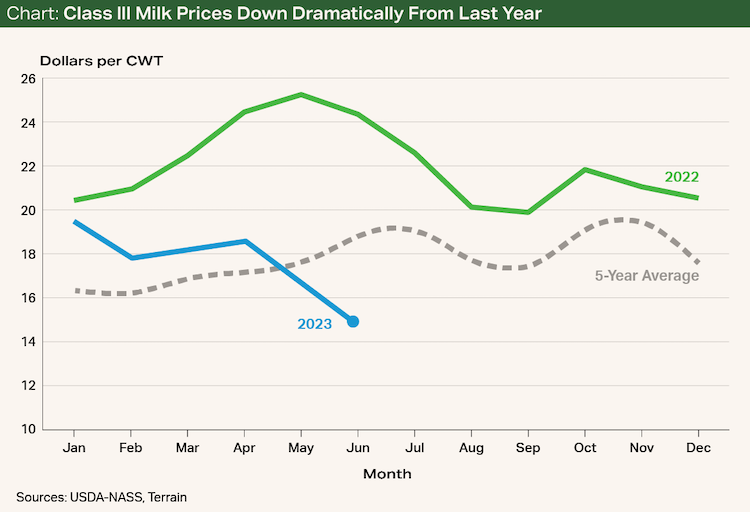

At the midpoint of 2023, milk prices are significantly worse than many, including me, expected coming into the year. Without a major demand surge expected from either the domestic or export markets, a slowdown in milk production might need to be the turning point for any price improvement in the second half of the year. But reducing supply at a national herd level doesn’t happen overnight, and the impact on prices can underwhelm.

The last time we saw a major swing in price levels from record highs to painful lows (setting aside the wild volatility of 2020) was from 2014 into 2015. The Class III price fell from $24.60 per hundredweight (cwt.) in September 2014 to $15.46 per cwt. by February 2015. At the time, cow numbers continued to climb slightly even after prices had collapsed, peaking in May 2015 at 9.33 million head before very gradually falling by about 28,000 head by January 2016 — not enough to shake markets out of what became a prolonged rut.

So far this year, despite the steady decline in milk prices, milk production has grown on a year-on-year basis every month, albeit modestly. Cow numbers have increased or held steady each month except April, which was marked by flooding in California and a tragic fire in Texas.

Producers have managed to hold on through the first part of the year for a couple of reasons.

- 2022 was a good year: Costs surged with inflation, but record-high milk prices were enough to overcome them. Coming into 2023 in fairly good shape, producers could withstand a couple of months of lower milk prices.

- Additionally, producers that took advantage of the high markets last year and purchased insurance through Dairy Revenue Protection (Dairy-RP) or used other hedging strategies have been insulated through at least the first two quarters, but the second half of the year could be a different story.

The amount of milk covered by Dairy-RP insurance in the second half of 2023 is about 37% below the amount covered in the first half of the year. And much of the coverage that was purchased for the second half of the year was purchased recently after prices were already falling, resulting in less favorable coverage. Other forms of risk management, like futures or forward contracts, likely followed a similar pattern.

Without some form of price protection, making milk is not profitable given farmers are feeding high-cost 2022 silage and receiving a Class III milk price near $15 per cwt. As hedges run out, and the margin pressure becomes more real, we may see more operational shifts to withstand the current environment.

With high cattle markets and a feed outlook that looks worse every passing day without rain in the Corn Belt, cull rates could begin to climb. Year to date, dairy cow slaughter is up nearly 21,000 head above the five-year average for this time of year and about 65,000 above last year. Dairy-beef cross programs are also providing a revenue boost and reining in the replacement heifer supply.

These factors could be the catalyst to drive a supply contraction in the second half of the year, which could provide support for prices, and that is good news. But history tells us that these supply responses are usually less dramatic (who likes to draw back on their herd?) than what the market needs to sharply turn prices around.