The Dairy Margin Coverage Program (DMC) is a risk management option utilized by many dairy farmers. It was first created by the 2018 Farm Bill as an updated — and many would say improved — version of the Margin Protection Program which itself was created in the 2014 Farm Bill. On an annual basis, dairy farmers can sign up for operation-specific coverage based on milk production history. The DMC program insures milk based on a nationally representative income-over-feed-cost margin of up to $9.50 per hundredweight (cwt.) for a relatively small fee.

As a result, DMC has become the foundation of market risk management by U.S. dairy farms — particularly for small and medium-sized herds. Since 2018, a majority of dairy farms and eligible milk production have participated as the program has become foundational to dairy farm risk management.

Secures major income source

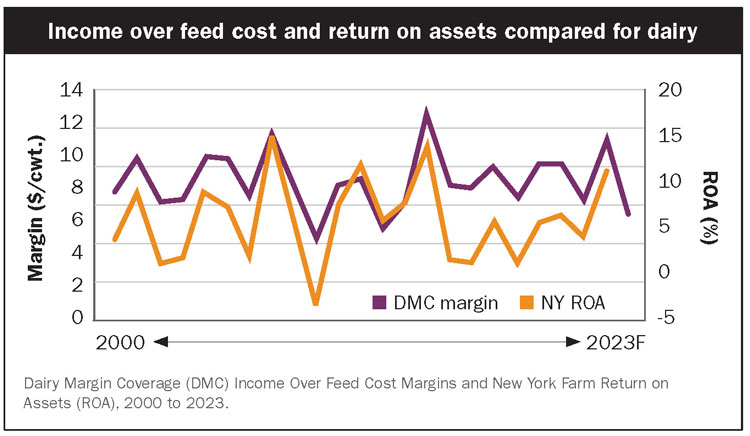

As milk is the largest source of revenue and feed is the largest expense, the income-over-feed-cost margin is a proxy for dairy farm profitability as well as the trigger for DMC payments. Had the program existed since 2000, the average margin from 2000 through 2022 would have been $8.75 per cwt. (see figure). Historically, about three-quarters of the variation in income-over-feed-cost margin has been driven by the milk price with the remainder due to feed prices.

There are multiple measures of dairy farm profitability. Profitability is the extent to which net income is generated to adequately cover costs, including a fair return to management and capital invested. To measure profitability, we use rate of return on assets without appreciation (ROA). This is defined as operating profit divided by total farm asset value, which controls for farm asset size. ROA measures before tax profitable earnings per dollar of investment in assets that reflect how efficiently the farm business uses all assets — whether borrowed or equity capital — to generate profit.

Dairy’s rate of return

Using the Cornell Dairy Farm Business Summary, the average rate of return on assets (without asset appreciation) for New York farms since 2000 was 6.1%. From the figure, it is clear that 2007, 2014, and 2022 were profitable years, while 2009 and 2012 resulted in large losses.

Using a definition that a “good” profit year was more than 25% above the average ROA, a “poor” profit year was more than 25% below average ROA and any year within that band was “average” profitability. The 23 years here included eight “good” years, six “average” years, and nine “poor” years.

Of particular importance is that, since 2014, every year until 2022 was either “poor” or “average.” Studying dairy farm financial resiliency makes it clear that “good” profitable years are necessary to recharge liquidity and solvency and ensure farm viability.

Does it work?

The figure displays a tendency for margins and profitability to move back toward the average value as milk production and consumption react to demand or supply shocks. One way to consider whether the DMC margin has been a good proxy for profitability is the correlation between ROA and the DMC margin, which on an annual basis was 77%. Thus, the DMC margin was highly correlated with dairy farm profitability.

The current forecast is for a drop in the income-over-feed-cost margin for 2023. As of this writing in the first week of July, the DMC income-over-feed-cost margin is forecasted, based on current milk and feed futures, to average $6.29 per cwt. for all of 2023. The result is more than $3 per cwt. in payments based on qualified milk at a $9.50 per cwt. margin coverage. Futures markets are efficient and unbiased estimators of milk and feed cost, but they are notoriously bad at predicting both supply and demand shocks.

The magnitude and ability of the DMC to form a foundation for dairy farm risk management makes the next farm bill of paramount importance. The current farm bill expires at the end of 2023, meaning discussions will ramp up this year. The result will be in either a new bill or an extension of the current farm bill legislation.

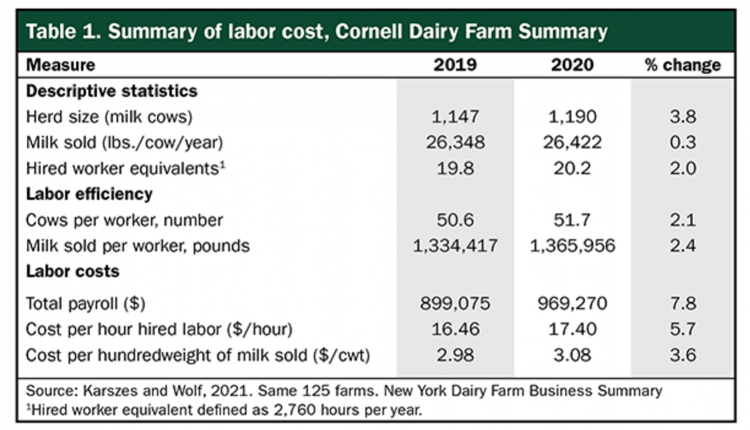

The DMC program may be revisited as far as production history, Tier 1 limits, and margin levels. The growing cost of both labor and energy certainly may indicate that margins do not translate to the profits levels they previously did. The average U.S. dairy farm produces about 8 million pounds of milk per year and a discussion of raising the Tier 1 amount — or perhaps creating an intermediate coverage tier — are likely to occur.

What changes, if any, that can be instituted for the DMC will depend heavily on projected “baseline” expenditures. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is a nonpartisan office in the legislative branch that estimates the 10-year cost of legislation, which is called the baseline.

The baseline assumes that the program continues as is and the costs are based off of projected prices. If there is a proposed change to a program — say an increase in margin or milk in Tier 1 — then the difference between what that is projected to spend and the status quo program are compared. It may be a heavy lift given current rules and congressional make-up to add spending to the DMC program.