The author is a dairy calf and heifer specialist with Vita Plus.

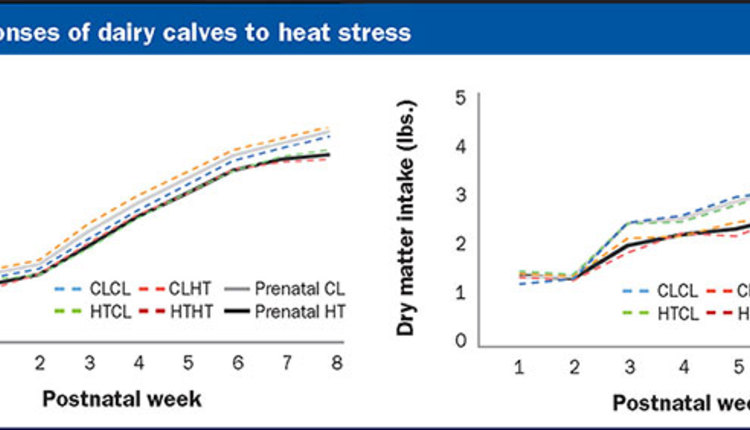

Many dairies are keen to review heat abatement strategies for their lactating herd. However, dairy cattle across all life stages are susceptible to heat stress and thus require attention in the summer plan. Calves are some of the most thermotolerant animals on a dairy farm because they are smaller and their rumens are still developing. Even so, calves are still at risk for poor welfare, reduced growth, and impaired health under certain conditions.

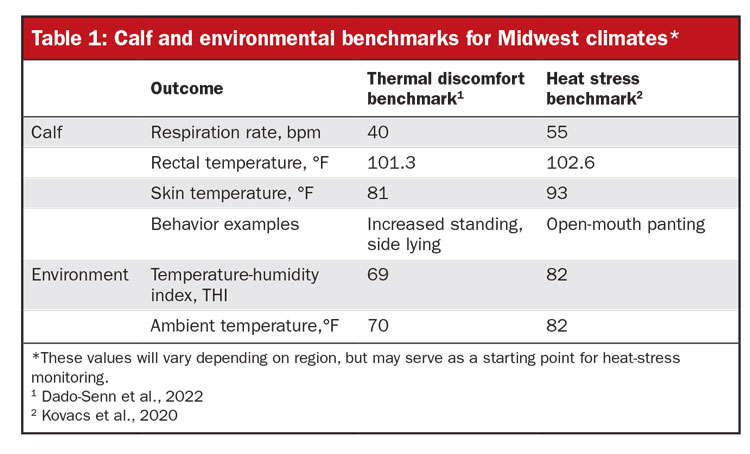

To detect heat stress in calves, assess nonproductive outcomes such as elevated respiration rate, increased rectal temperature, and changes in calf behavior. In addition, look at productive outcomes such as reduced grain intake, greater water intake, lower average daily gain, and elevated respiratory disease. These signs are indicative of either thermal discomfort or physiological heat stress.

Be a careful observer

Thermal discomfort occurs at lower ambient temperatures when a calf starts to breathe faster, sweat more, and change behavior to maintain body temperature, which impacts calf welfare but not productivity. Heat abatement should start at or before these signs to promote calf comfort and avoid any negative productive outcomes. Physiological heat stress occurs at higher ambient temperatures when those changes in calf responses are no longer able to maintain a constant core body temperature, leading to shifts in calf health, feed intake, and daily gains.

To monitor calf thermal discomfort and heat stress, one can use a variety of calf-side or environmental benchmarks. For midwestern, western, and southwestern U.S. regions, ambient temperature is likely the best environmental measurement of heat stress, whereas temperature-humidity index is a better measure for dairies in the southeastern U.S.

Respiration rates are measured by counting flank movements per minute. Skin temperature is determined via infrared thermometer. Both calf-side strategies are simple and efficient calf thermoregulation measures and good for scanning herd-level concerns. However, rectal temperature is the best gauge of core body temperature, ideal for monitoring individual calves when possible.

Implement a plan

If calves have reached threshold levels, heat stress may be mitigated through changes in calf housing or feeding program. The ideal option for your operation depends on housing style and feasibility as well as the severity and duration of heat stress.

Pasture: For calves housed on pasture, shade is a simple and inexpensive heat abatement method. Shade via trees, shade cloths, or lean-tos block solar radiation and can help lower calf skin and body temperatures during hot weather.

You may notice that pastured heifers seek out patches of shade in the summer months, even if it means bunching close together. That’s why it’s important to offer ample shading opportunities. Provide 11 to 20 square feet of shade per head and use material that provides 60% to 100% shade block. Keep areas under the shade as free from pests and mud as possible and provide water sources near the shade to encourage water intake. Shade is not as effective in cooling calves relative to providing more active heat abatement, but it is an essential first step in pasture systems.

Outdoor hutches: Although outdoor calf hutches offer shade, their insulation-based design means that hutches have elevated internal temperatures in the summer and can do more harm than good if not properly ventilated or supplemented with additional shade. To maximize hutch passive ventilation, open rear or side hutch windows. You may also prop up the rear of calf hutches, but limit the potential for escapees. These modifications generate air speeds of about 0.33 miles per hour, which has been shown to improve calf respiration rates and rectal temperatures without greatly impacting calf intake or growth. Other modifications like hutch orientation to maximize daily shade or adding reflective covers are also used on-farm with varying success.

Indoor housing: Indoor housing inherently allows continuous shading, but it requires additional attention to ventilation. While winter and spring ventilation maintains air quality with six to eight air changes per hour, the summer months require 20 air changes per hour to promote both air quality and heat abatement. This can be accomplished by opening curtain sidewalls, maximizing positive pressure tubing, and/or installing ceiling or basket fans. Research has not yet settled on an ideal air speed to achieve these summer targets, but investigated levels range from 2 to 4.5 miles per hour with reported improvements in calf thermoregulation, intake, and health.

When assessing air movement on farm, monitor both the whole-barn air exchanges and air speeds directly at the calf level using an anemometer, particularly if calves are individually housed. Work with an air quality specialist in your area to determine the right combination of technologies that fit your environment.

Re-evaluate feeding

Regardless of the housing scenario, the risk factors of heat stress can be minimized by maintaining a consistent and attentive feeding program. Offer a fresh, warm, and continuous supply of water. Providing prophylactic oral electrolytes can also help during more extreme bouts of heat stress to both encourage water intake and replenish minerals and blood pH after sweating and panting. Feed intake may also drop in the summer, so monitor overall energy demands and adjust milk feeding strategies accordingly.

Although it may seem impractical to cool nonlactating animals, keeping the youngest members of the herd in mind when developing summer strategies can protect the future productivity of your operation. By monitoring calf thermal discomfort and providing simple and timely heat abatement, we can promote calf welfare and encourage ideal growth and health trajectories from birth to lactation.