Dairy rations are balanced on the cents per cow that an ingredient will add to or cut from a feed budget. Yet, if we watch a ration being mixed, it's not uncommon to see finely ground feed ingredients blow away with the wind. What if we viewed this dust and debris as more than just a cost of doing business?

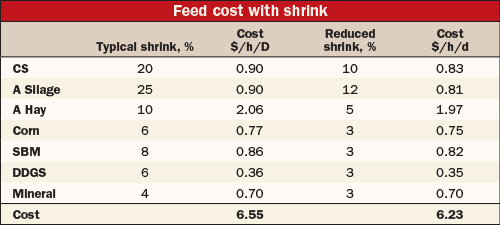

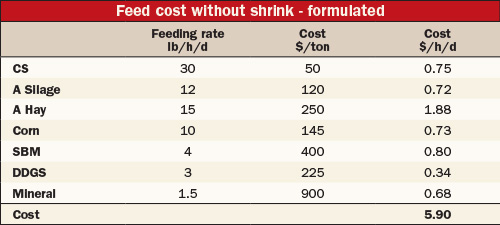

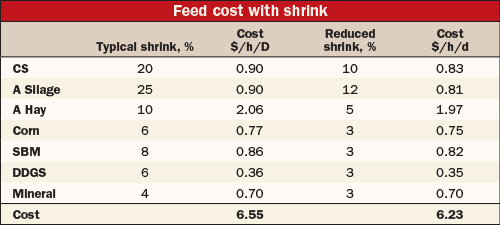

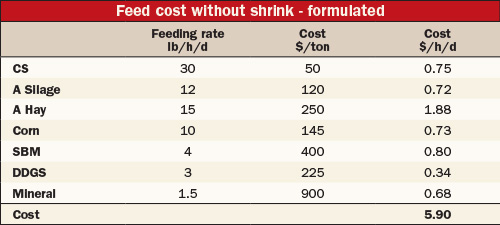

At its most basic level, shrink is the difference between the amount of feed delivered and the amount that is fed, noted Mike Brouk, with Kansas State University, at the Leading Dairy Producers Conference. Shrink is a potential profit opportunity on all dairies, but it's not an area destined for improvement unless it is measured.

While it's caused by any number of factors, shrink is most often associated with excess moisture, spoilage or losses due to wind and animals. Delivery weight errors, scale inaccuracies, cows tossing feed, refusals, rodents, tires and tracking also present challenges. Finally, noted Brouk, starlings will sort the diets for us. Research has shown that, in diets containing flaked corn or corn silage, starlings can reduce dietary starch by 55 percent.

"One of the big areas where we lose on farms is our forages," noted Brouk. It takes a lot of additional acres to account for shrink. If 35 percent of harvested feed is lost on farm, another 19.2 acres are needed to compensate and make feed budgets balance, assuming 20 tons of corn silage per acre. With 15 percent shrink, another 8.2 acres are needed to make up the difference.

"Reduced losses are associated with improved forage quality, as well," he added.

There are returns in reducing shrink. We need to move toward looking at it as a net profit center. Yet, a producer has to believe their shrink numbers, noted Brouk. Until they buy in, they're unlikely to do anything about it.

The author , Amanda Smith, was an associate editor and is an animal science graduate of Cornell University. Smith covers feeding, milk quality and heads up the World Dairy Expo Supplement. She grew up on a Medina, N.Y., dairy, and interned at a 1,700-cow western New York dairy, a large New York calf and heifer farm, and studied in New Zealand for one semester.

At its most basic level, shrink is the difference between the amount of feed delivered and the amount that is fed, noted Mike Brouk, with Kansas State University, at the Leading Dairy Producers Conference. Shrink is a potential profit opportunity on all dairies, but it's not an area destined for improvement unless it is measured.

While it's caused by any number of factors, shrink is most often associated with excess moisture, spoilage or losses due to wind and animals. Delivery weight errors, scale inaccuracies, cows tossing feed, refusals, rodents, tires and tracking also present challenges. Finally, noted Brouk, starlings will sort the diets for us. Research has shown that, in diets containing flaked corn or corn silage, starlings can reduce dietary starch by 55 percent.

"One of the big areas where we lose on farms is our forages," noted Brouk. It takes a lot of additional acres to account for shrink. If 35 percent of harvested feed is lost on farm, another 19.2 acres are needed to compensate and make feed budgets balance, assuming 20 tons of corn silage per acre. With 15 percent shrink, another 8.2 acres are needed to make up the difference.

"Reduced losses are associated with improved forage quality, as well," he added.

There are returns in reducing shrink. We need to move toward looking at it as a net profit center. Yet, a producer has to believe their shrink numbers, noted Brouk. Until they buy in, they're unlikely to do anything about it.

The author , Amanda Smith, was an associate editor and is an animal science graduate of Cornell University. Smith covers feeding, milk quality and heads up the World Dairy Expo Supplement. She grew up on a Medina, N.Y., dairy, and interned at a 1,700-cow western New York dairy, a large New York calf and heifer farm, and studied in New Zealand for one semester.