The year is 1871 . . .

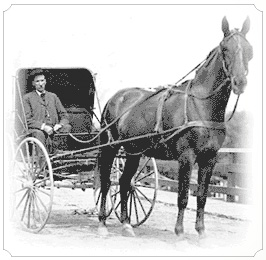

The year is 1871 . . .A July sun bakes down on the rolling Wisconsin countryside. Up a dirt road a covered buggy leaves a low drift of dust which slowly settles, waiting to be stirred again by the next horse and buggy traveler.

But this solitary buggy carries a tall Lincolnesque figure, who, in the next few hours, will make a decision which will affect the lives of every man, woman and child in his state, and eventually the nation.

As he nears the crest of the hill, his mind is occupied with the day-to-day problems of any small-town weekly newspaper editor with a growing family. Since moving West from his upper New York State farm home, life's road has been rough. Only long, dedicated hours have kept his pioneering publishing venture in the black. But this is the lot of the pioneer and he accepts it, taking satisfaction in the personal inner rewards to those who serve their fellow man.

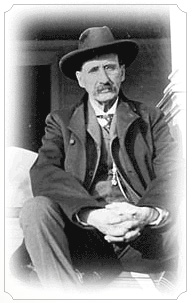

When his bay mare slows at the top of the hill, the driver eases his rig to a stop and his horse settles with a sigh of relief. From this hill, William Dempster Hoard can view his adopted state. He sees all around him fields of wheat rapidly ripening in rolling fields.

. . . but the stands are thin.

. . . in fact, the yields have been falling each successive year.

. . . on the next hill to the north is an abandoned set of farm buildings, now owned by the bank as the former owner gave up and moved farther west to new land.

. . . there are other farms like this in the area.

Why should this be so?

An uneasy doubt enters the editor's thinking. His logical mind explores the possible causes.

. . . low fertility and the chinch bug have taken their toll. Wheat yields in recent years have dropped to a low of eight bushels per acre.

. . . maybe those who left were poor farmers, incapable of success in farming.

. . . but he knew many of them and this was not true.

. . . there must be a more fundamental reason.

Hoard finds it in his childhood memories and his rudimentary knowledge of geology. This is glacial soil. These Wisconsin farms really rest on a thin foundation of topsoil, not at all like that of the unglaciated prairie land of Illinois, Indiana and Iowa.

Hoard finds it in his childhood memories and his rudimentary knowledge of geology. This is glacial soil. These Wisconsin farms really rest on a thin foundation of topsoil, not at all like that of the unglaciated prairie land of Illinois, Indiana and Iowa.Then Hoard recalls how farmers in New York State had mined their fields with continuous wheat, too. The dairy cow had been the salvation of many of those neighboring farms. The healing power of her grassland and the humus and fertility of her droppings had revived tired acres, made them bear again as they had years ago when broken from virgin timber.

As Hoard's horse dozes in the July sun, the lanky editor is lost in thought. The outline of an editorial begins to form in his mind. But it is more than an editorial. This should be an editorial campaign in his weekly newspaper, the Jefferson County Union. In fact, the need is so great he could devote his life to no greater cause.

-And thus a crusade was born.

From that day forward, Hoard became the apostle of the dairy cow for a permanent, prosperous, soil-conserving agriculture. He was to live to be honored nationally and internationally, be cited as the "father of American dairying," and be quoted generations after his passing.

In the beginning, however, Hoard's crusade fell on unreceptive ears. Tradition bound farmers, in the well-worn seasonal rut of plowing, planting and harvesting wheat, wanted no part of the year-round chores which were the obligation of the dairy husbandman. The passive resistance of these stolid Nordic farmers would have chilled the enthusiasm of anyone less dedicated than Hoard.

But time and economics were the editor's allies. As crop income dwindled, more of the farmers listened to Hoard. Though questioned and challenged at his every appearance, Hoard's arguments dented the crust of farming habit and a few dairy cows began to appear on the hills and in the valleys of Jefferson County.

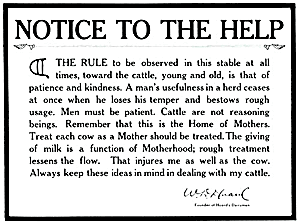

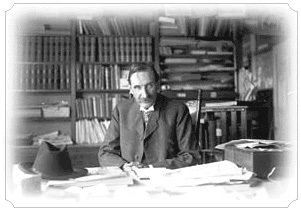

This new type of agriculture brought with it a demand for information. Feeding, breeding and management of the dairy cow, and marketing of milk and cream were foreign to the lives of these new dairymen. Hoard filled his paper with the knowledge he had gained in his native New York and drew liberally on the advice of a few advanced dairymen in the East and even in Europe. A prodigious reader, Hoard combed every farm periodical and corresponded with anyone who gave promise of providing the most reliable information available.

His crusade rapidly outgrew his country weekly. In 1885 a national dairy farm magazine was launched. To supplement the power of the written word, he took to the speaker's platform to fulfill engagements throughout the land. His training for the ministry as a young man helped him become known as one of the greatest speakers of his time, a period characterized in history as an era of colorful speakers and leaders of men.

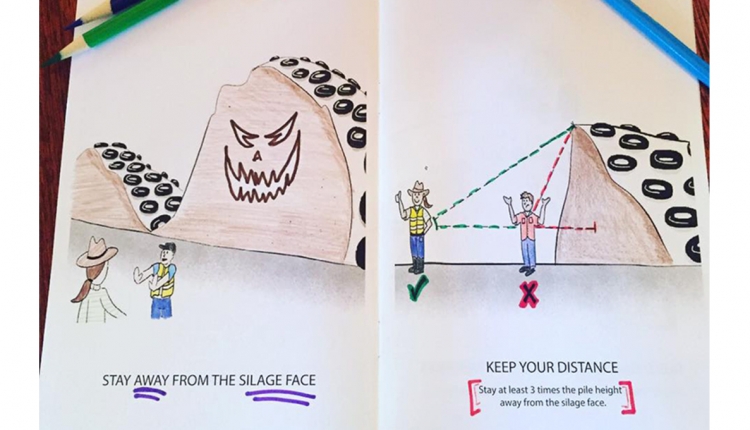

It should be remembered that when Hoard began his crusade, America's dairy industry was not unlike that which still prevails in many countries of the world. On city streets, wagons carried battered cans of warm milk. A tin dipper was used to fill the housewives' pans and pitchers. Among the millions of multiplying bacteria in the milk were tubercle bacilli, Brucella abortus and many other human health hazards. Butter made from sour cream was of varying quality and often adulterated with beef tallow and vegetable fats.

These were the challenges before Hoard. In the beginning, he little realized the magnitude of the task he had undertaken. As dairy farming expanded, however, he came to grips with the tangled problems of sanitation, health and marketing, as well as those of dairy husbandry. All of his mental and physical resources were thrown into the struggle to build what has become the most stable part of U.S. agriculture.

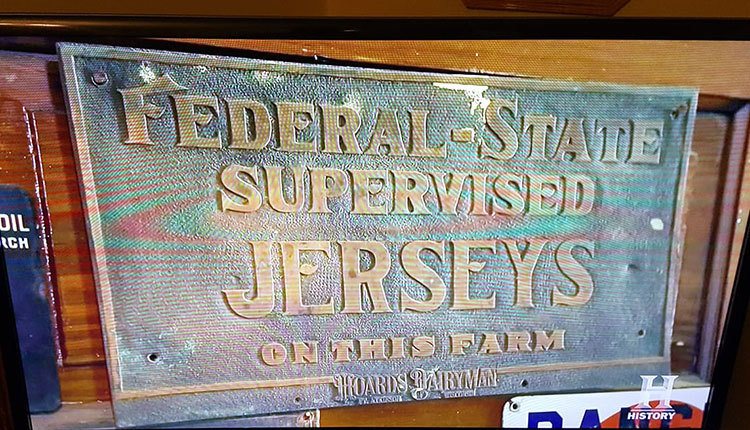

Great men have come and gone, but rare is the man who has lived on as Hoard. Today, more than 135 years after that hilltop decision, his crusade carries on through Hoard's Dairyman, the magazine he founded in 1885. A son and grandson, in successive generations, added materially the luster of the name and the quality of the service to man.

A multi-billion-dollar dairy industry today serves all Americans the highest quality dairy foods available to any people on earth. Nowhere else in the world can be found such quality and safety in this most nearly perfect food . . . and it is found in such abundance.

The beneficent creature which Hoard and his successors championed has healed the soil sores of a continent, from the thin, glaciated soils of the North to the eroded red gullies of the South.

Today, more than 13 decades following the hilltop decision, let us review briefly the great service rendered by the "father of American dairying," and his lengthened shadow, Hoard's Dairyman, the National Dairy Farm Magazine.