I routinely track the hay fundamentals at a high level to generate supply and demand balances. This, in turn, drives my alfalfa price forecast, which is an important part of the dairy ration. But after reading the article Alfalfa and almonds are in a battle for water about the ongoing drought and impact on alfalfa and almond production in California, I decided to dig a little deeper on the situation.

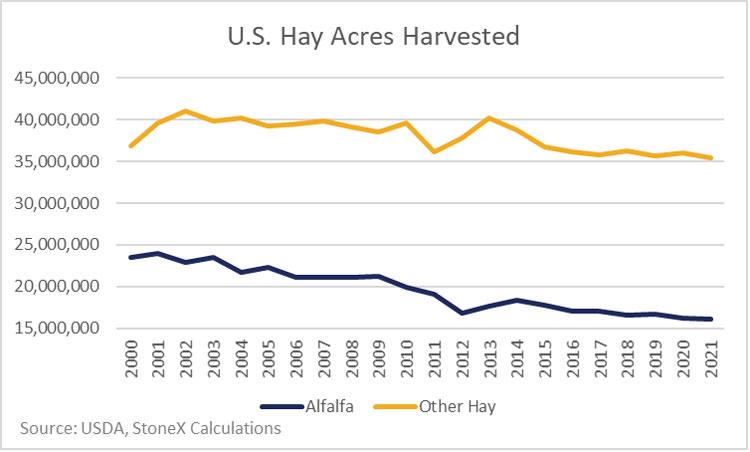

Alfalfa acres harvested in the U.S. have generally been trending lower since 2000. Acreage for other hay has generally been trending downward, too. There is some price sensitivity to acreage. If alfalfa prices get high enough, farmers seem to plant more of it the following year. As for this season, USDA is estimating a small drop in U.S. alfalfa that may also have some correlation to high grain prices and more interest in those crops.

One downside to alfalfa is that it is perceived as a thirsty crop. Part of the reason is because, where the climate can support it, alfalfa is grown year-round. If farmers are growing corn or wheat year-round, they would use more water as well.

Second, alfalfa has a relatively high yield per acre compared to other hay, which requires more water to grow. So you could argue that alfalfa, as it is being grown in places like California, is taking a lot of water, but it isn’t dramatically more water per unit of output than what you would get with other crops.

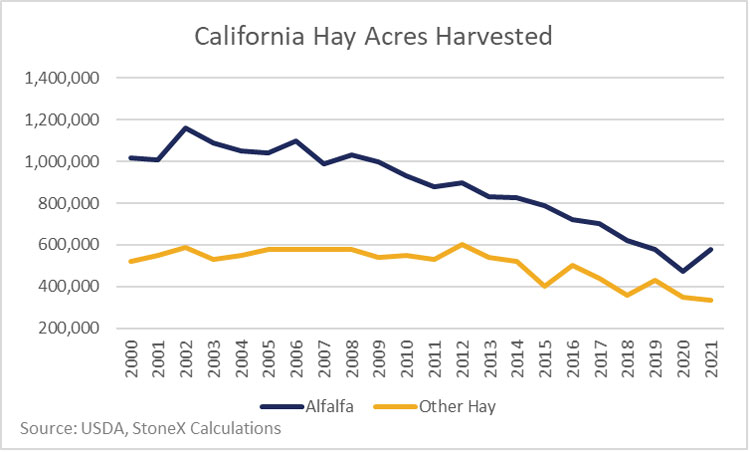

With that said, the number of acres of harvested alfalfa in California has been trending sharply lower since 2002. California alfalfa acreage is down 50% since 2002, while alfalfa acres in the rest of the country are only down 28.5%. The Hoard’s Dairyman Intel covered it well; the story behind the decline in California alfalfa acreage is tied to the limited water resources and rise in almond production in the state.

Yields hold nearly constant

Acreage is only half of the production story; the other half is yields. In warm states, where the alfalfa can be grown year-round and is often irrigated, yields can be in the 7 to 9 tons per acre range. In colder states, where the number of cuttings is limited by the weather and where irrigated alfalfa fields are less common, yields are typically down in the 2-to-4-ton range. But what really surprises me about alfalfa is that those yields are relatively stable. For instance, the difference between the highest yielding year in California and the lowest yielding year is only 7.5% over the past 20 years. At the national level, the corn yield has varied by 43% over that timeframe.

There is some obvious concern that the drought in California and throughout much of the western U.S. is going to hurt hay and alfalfa yields. When I compare the Palmer Drought Index for California against California alfalfa yields, I have a hard time finding a statistical connection between the two. California was very dry in 2014, yet yield was only slightly below average. California was on the dry side in 2020 as well, and the alfalfa yield matched the highest level seen in the past 20 years.

There is always a risk that “this time will be different.” Maybe continued pressure on water resources means water gets diverted to other uses this time, but if this time is like past droughts, the impact on yield may be limited.