At the recent American Association of Bovine Practitioners (AABP) annual conference, Patrick Crannell, a student at the Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine, discussed the impact good – and more specifically, not so good – transfer of passive immunity can have on animal health.

Due to the thickness of a cow’s placenta, immunoglobulins do not transfer from the dam to the fetus. Instead, immunoglobulins must be acquired through colostrum. If a calf does not receive enough immunoglobulins, that is considered a failure to transfer passive immunity.

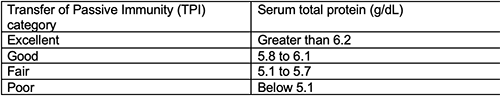

Crannell said a long-time industry standard used 5.2 grams per deciliter (g/dL) as the cutoff for successful transfer of passive immunity. More recently, though, industry professionals proposed a four-point scale to evaluate the exchange of immunity. The new scale includes the categories of excellent, good, fair, and poor.

In a retrospective observational study involving one 3,500-head dairy in Michigan, Crannell said they looked at serum total protein levels in calves between 2 and 7 days of age. There were 1,729 calves that fell into the excellent category, 1,456 that were classified as good, 905 were fair, and 246 calves were considered to have poor transfer of passive immunity. As one part of the study, they looked at morbidity and mortality rates in these calves.

For diarrhea, calves in the poor category were 1.49 times more likely to get sick than calves in the excellent category. Those in the fair category were 1.42 times more likely to get diarrhea, and calves classified with good transfer of passive immunity were 1.14 times more likely experience this illness.

Crannell pointed out that most of the diarrhea cases were happening prior to 2 weeks of age. “It is not surprising that an animal with a higher serum total protein did better at protecting itself against diarrhea because, while the calf develops its own immunity, it needs to rely on passive transfer of immunity,” he noted.

With pneumonia, calves in the poor group were 1.39 times more likely to get sick than calves that were in the excellent category. No differences were observed for calves that fell into the good and fair categories.

“As transfer of passive immunity wanes, an animal becomes more susceptible to other pathogens,” commented Crannell. He said it showed in this herd, where the calves with poor transfer of passive immunity were more susceptible to pneumonia.

“Higher serum total protein provides an animal with greater protection,” Crannell stated. “An animal with a reduced immunoglobulin load is more susceptible to any disease, and then they are more likely to acquire a secondary disease.” He reiterated that until a calf develops its own indigenous humoral immunity response to pathogens on the farm, it relies on serum total protein, emphasizing the importance of a successful transfer of passive immunity.