The author is a professor emeritus in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Michigan State University.

About 10% of U.S. dairy cattle were infected with the bovine leukemia virus (BLV) in the 1960s and 1970s. Now, about a third of our nation’s beef cattle and almost half of our dairy cattle are infected with this lifelong, incurable virus. Meanwhile, more than 20 countries eradicated this virus from their livestock by culling all cattle with BLV antibodies — usually determined by an ELISA test on milk or blood.

Like its cousin HIV/AIDS, BLV compromises cattle immune systems, which enables the development of many other diseases and conditions. A 2013 study in Michigan showed that BLV-infected cattle were 23% more likely to be culled or die than their BLV-negative herdmates of the same age. This study was repeated a few years later using herds from nine states, and this time an even greater 30% difference was found between ELISA-positive versus ELISA-negative cattle.

Poor cow longevity (lifespan) is an animal welfare issue as well as an economic one. Our research group and others have repeatedly shown an association between BLV infection and reduced milk production in dairy cattle. Additionally, BLV-induced lymphoma is now the leading cause for cattle being condemned at slaughter facilities in the U.S.

Historically, BLV was not seen as causing any human health problems, but this is now being challenged by some controversial findings claiming an association with human mammary tumors. Altogether, there are now sufficient reasons to control this livestock disease.

A new testing option

BLV has typically been controlled by testing the entire herd and then culling all antibody positive cattle. The countries that eradicated BLV were often starting with a very low prevalence, so usually only a few infected cows per herd needed to be culled.

With such a high prevalence in most U.S. herds, it is economically prohibitive to simultaneously cull so many cows as well as young stock. However, we have recently found that most of the antibody-positive cows rarely transmit the infection to their herdmates and their culling can be delayed —perhaps indefinitely.

A new laboratory test can measure a cow’s BLV proviral load (PVL), which is the concentration of the infectious BLV provirus in the blood and other body fluids. The highest PVL measurements can be many thousand times higher than the lowest values. PVL testing is available nationally through the Dairy Herd Information (DHI) testing service and is usually only done on ELISA-positive cows as determined by milk testing, also available through DHI.

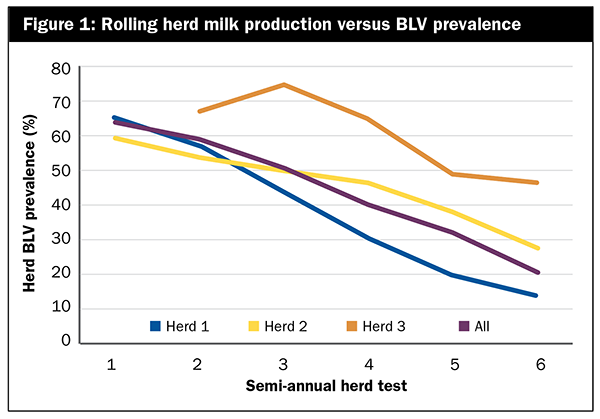

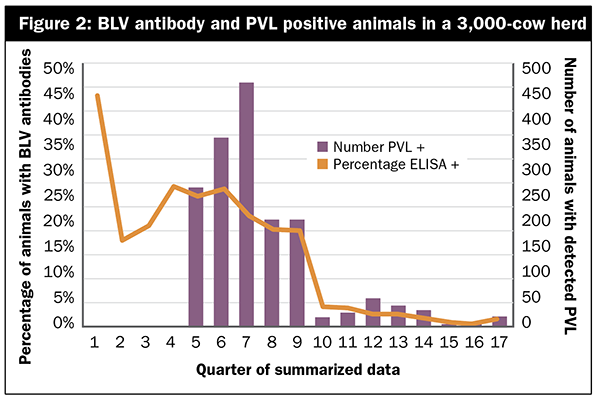

Cattle with very high proviral loads — often called “super-shedders” — are responsible for most of the new infections among their herdmates. Usually one-third or fewer of the ELISA-positive cows have such a high PVL that the herd managers want to cull or segregate them immediately. We have found that once the highest PVL cows are removed, the rate of new infections drops rapidly (Figures 1 and 2).

When the BLV prevalence drops to a sufficiently low level, the producer can cull all the remaining ELISA-positive cows and be done with the infection for good. We have found that herds can remain free from BLV even when neighboring herds are infected. Fortunately, PVL changes relatively slowly, so annual PVL testing of ELISA-positive cows may be sufficient.

Producers often ask how high of a PVL necessitates culling or segregation. The herds described in Figures 1 and 2 all started removing cows with the highest PVL to the extent they believed economically possible. Over time, they culled cows with progressively lower PVL values.

Step one is to do a milk ELISA test on your milking cows. Then ask for a PVL test on those found to be ELISA-positive.

Concluding thoughts

Over 20 mostly European nations have already eliminated this pathogen from their livestock, while BLV currently infects almost all U.S. dairy herds and nearly half of U.S. dairy cows. It causes immune disruption, reduced production, shortened cow lifespan, decreased animal welfare, and consumer concern over possible human health issues.

Culling only those cattle with the highest PVL allows the retention of the majority of infected (ELISA-positive) cattle that have low PVL values, making them of minimal infectious risk to their herd mates. A growing number of dairy producers are using this new method of controlling BLV in their herds.