From 2023 to 2025, there is expected to be over $6 billion in new milk processing capacity under construction in the U.S. That is a strong signal that companies are willing to invest significant amounts of money to supply a growing demand for dairy products in both the domestic and export markets. This also stands in contrast to Europe and Oceania where little new investment is taking place as future milk growth is limited. While this is an exciting time for the U.S. dairy industry, the wave of investment has raised a number of questions.

The first question being asked is, “Where will the milk come from?” Milk production was below year-ago levels for the second half of 2023 with continued contraction of the nation’s dairy herd and flat to lower milk per cow. Milk output in key regions, including the Upper Midwest, Mideast, and New York has been growing, which will help fill capacity at new plants in those areas. The Southwest and California have seen most of the losses.

A contraction of the herd

The limiting factor to any growth in milk production is cow numbers, which slipped lower once again in December despite much lower cow culling. Not surprisingly, the drop in the national dairy cow herd is largely a result of two states — New Mexico and Texas, which were down 44,000 head compared to December 2022. The U.S. total was down 39,000.

The U.S. dairy herd fell 1,000 head from November to December, but only three of the top 23 states posted month-to-month declines, with a loss of 5,000 head in New Mexico dragging down the U.S. total. Improving margins should result in modest growth in cow numbers, but the lack of replacement heifers presents challenges to farms that want to expand.

The January 31 USDA Cattle Inventory Report confirmed what many dairy farmers have known for quite a while — dairy heifers are hard to find. However, the surprise was a large downward revision in the January 1, 2023, numbers, with USDA dropping the total dairy heifer inventory by 5% and the number expected to calve in 2023 by 6%.

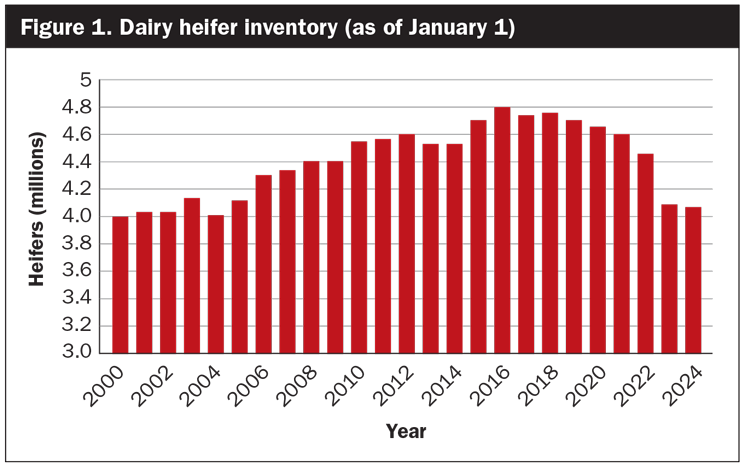

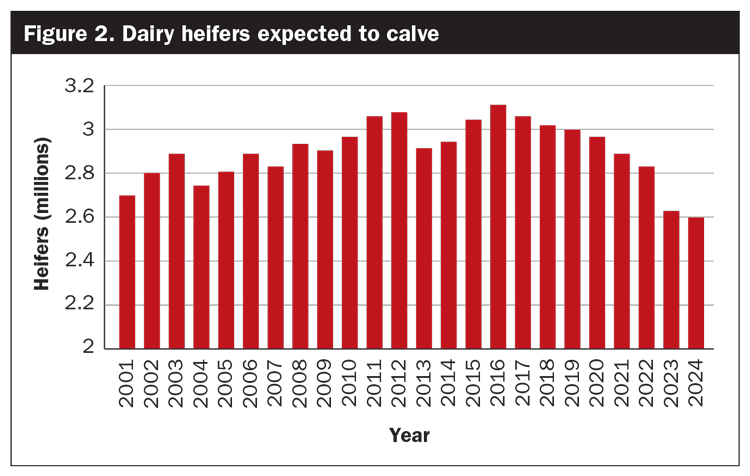

On January 1, 2024, the number of dairy heifers over 500 pounds was 4.059 million head, the lowest inventory since 2004 and down 0.4% from last year (Figure 1). Meanwhile, the number of heifers expected to calve in 2024 was only 2.593 million, down 1.1% from last year and the lowest since USDA starting tracking that category in 2001 (Figure 2). This is well below the average of 3.04 million head seen between 2015 and 2020.

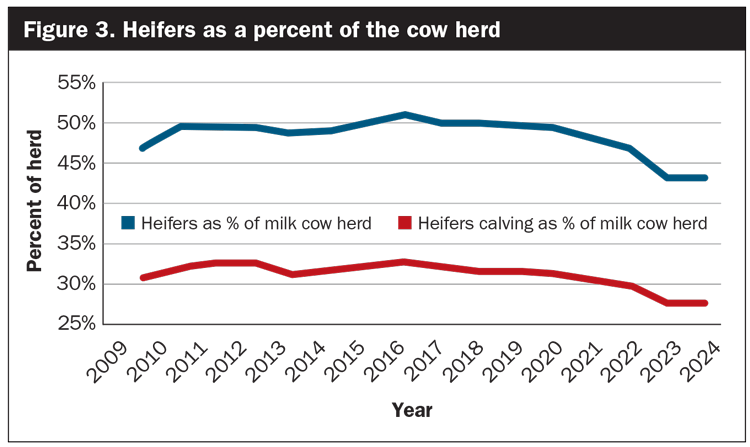

As a percent of the cow herd, the number of heifers calving this year is only 28%, also the lowest on record (Figure 3). For farms that want to expand in 2024, the lack of replacement heifers and the high cost for those that are available are limiting factors.

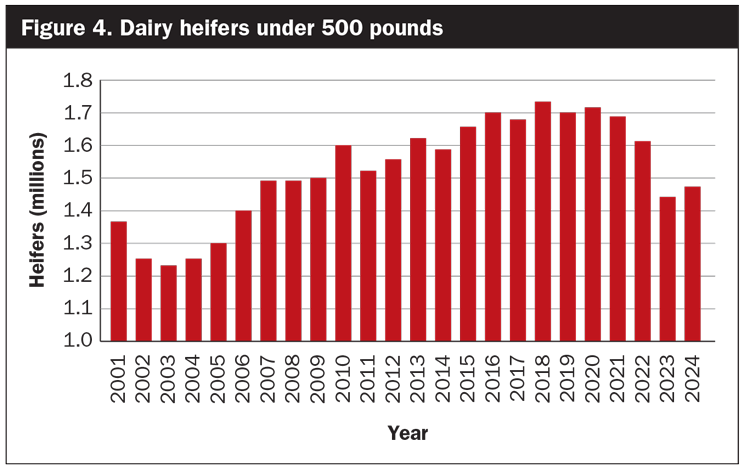

Looking ahead, there was a small bump in the number of heifers under 500 pounds, which could provide a slight boost to the number of heifers entering the herd in 2025 (Figure 4). However, high beef prices are expected to continue, which is a disincentive for farms to hold back dairy heifers for milking.

For perspective, only a few years ago, dairy bull and heifer calves were worth little, maybe $25 to $50 per head. In recent weeks, auction prices for Holstein bull calves were $300 to $400 or more. If they were dairy-beef crosses, prices were even higher — $600 to $700 per head.

This is a significant source of income for dairy farms, and during times of low milk margins, the decision to sell heifer calves versus raising them for replacement is easy; they sell and take the money. This is especially the case for farms that don’t need many replacement heifers.

In short, the industry has lost a substantial number of dairy heifer “free agents” and it doesn’t look to improve this year given continued high beef prices and dairy margins that don’t spur herd expansion.

A bright future remains

Will there be enough milk to meet current and future demand? In most regions with new plant activity, expansion is being discussed with some farms moving ahead with growth plans. Higher costs for buildings, cows and heifers, and labor are all factors holding back more rapid expansion.

The Southwest is likely the most challenged with new milk growth given the trends in Texas and New Mexico. More demand for milk could push premiums and milk prices higher, which would eventually incentivize growth in milk production.

While it is easy to get down about the current milk prices, the future for the U.S. dairy industry seems bright. Long-term trends are positive for dairy demand, and with limited supply growth in major export regions, the U.S. is well positioned to take advantage of those trends. Companies are investing in growth and producing products consumers are demanding. The challenge for dairy farms and processing plants will be to determine how their business can prosper in this growing industry.