Replacement heifers have long been viewed as a two-year economic sinkhole. "While heifer programs usually rank as the second largest cost of producing milk, the expense associated with feeding and rearing youngstock should be viewed instead as an investment in the future," noted Michael Overton, Elanco Knowledge Solutions, at the Cornell Nutrition Conference.

In the heifer growth cycle, the most costly portion is the preweaning period. Traditionally, a calf was fed a 20:20 milk replacer at 8 to 10 percent of body weight. Especially in colder weather, this diet burned brown fat and left calves in a semi-starved state.

In recent years, more intensive management programs have cropped up. These programs involve feeding rations that are higher in metabolizable protein without enough extra energy to promote fattening. During the milk-feeding period, calves are provided larger volumes of milk or milk replacer (28:20).

At the conference, Overton described the heifer raising economic model he developed while at the University of Georgia. The model divided the heifer life cycle into six stages. The summary of the net results for conventional versus intensive rearing systems (assuming an initial calf value of $175 and interest cost of 8 percent) are in the table below.

In the long run, conventionally fed calves are less efficient as they spend more days on feed without producing milk. In addition to an efficiency boost, their intensively fed counterparts have a reduction in morbidity and mortality and earlier age at first calving. In addition, fewer heifers are required to keep the replacement stream full and those that do enter the milking herd produce upwards of 1,700 pounds more milk in their first lactation.

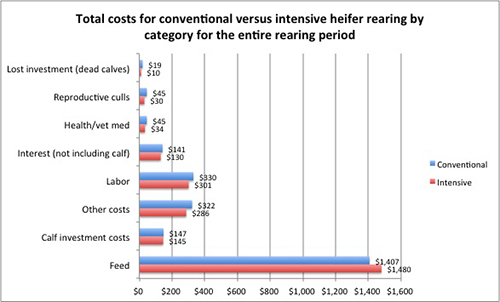

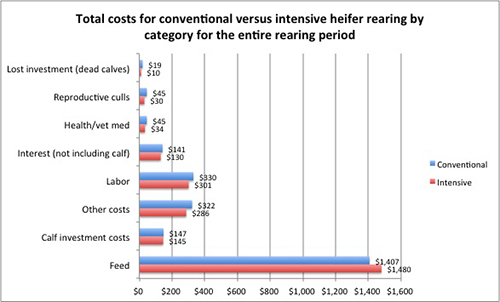

Throughout each growth stage, the intensive system costs more per day (figure), but the conventional system results in a higher total cost per heifer due to the longer feeding period. The total rearing cost is estimated to be $2,449 and $2,415 for the conventional versus intensive heifers, respectively. This does not account for the extra value of additional milk anticipated in the first lactation.

Additionally, the conventionally raised heifers, calving in at 24 to 26 months consume 12,473 pounds of feed with a cost per pound of gain of $1.85. The intensive group, on the other hand, consumed 11,775 pounds of feed and had a cost per pound of gain at $1.36.

The author, Amanda Smith, was an associate editor and is an animal science graduate of Cornell University. Smith covers feeding, milk quality and heads up the World Dairy Expo Supplement. She grew up on a Medina, N.Y., dairy, and interned at a 1,700-cow western New York dairy, a large New York calf and heifer farm, and studied in New Zealand for one semester.

In the heifer growth cycle, the most costly portion is the preweaning period. Traditionally, a calf was fed a 20:20 milk replacer at 8 to 10 percent of body weight. Especially in colder weather, this diet burned brown fat and left calves in a semi-starved state.

In recent years, more intensive management programs have cropped up. These programs involve feeding rations that are higher in metabolizable protein without enough extra energy to promote fattening. During the milk-feeding period, calves are provided larger volumes of milk or milk replacer (28:20).

At the conference, Overton described the heifer raising economic model he developed while at the University of Georgia. The model divided the heifer life cycle into six stages. The summary of the net results for conventional versus intensive rearing systems (assuming an initial calf value of $175 and interest cost of 8 percent) are in the table below.

| Outputs | ||

| Calf investment cost at calving | ||

| Age at first service | ||

| Average age at first calving | ||

| Average daily gain (lb./d) | ||

| Total rearing cost/heifer | ||

| Average cost/day | ||

| Additional milk in first lactation | ||

| Culling risk - first lactation | ||

| Add. milk value (lact = 1) | ||

| Net cost/heifer | ||

| Additional profit for Intensive |

In the long run, conventionally fed calves are less efficient as they spend more days on feed without producing milk. In addition to an efficiency boost, their intensively fed counterparts have a reduction in morbidity and mortality and earlier age at first calving. In addition, fewer heifers are required to keep the replacement stream full and those that do enter the milking herd produce upwards of 1,700 pounds more milk in their first lactation.

Throughout each growth stage, the intensive system costs more per day (figure), but the conventional system results in a higher total cost per heifer due to the longer feeding period. The total rearing cost is estimated to be $2,449 and $2,415 for the conventional versus intensive heifers, respectively. This does not account for the extra value of additional milk anticipated in the first lactation.

Additionally, the conventionally raised heifers, calving in at 24 to 26 months consume 12,473 pounds of feed with a cost per pound of gain of $1.85. The intensive group, on the other hand, consumed 11,775 pounds of feed and had a cost per pound of gain at $1.36.

The author, Amanda Smith, was an associate editor and is an animal science graduate of Cornell University. Smith covers feeding, milk quality and heads up the World Dairy Expo Supplement. She grew up on a Medina, N.Y., dairy, and interned at a 1,700-cow western New York dairy, a large New York calf and heifer farm, and studied in New Zealand for one semester.