During the dog days of August, temperatures can rise to uncomfortable levels in even the most well ventilated, animal friendly barns, leaving cows on a hunt for the coolest spot available.

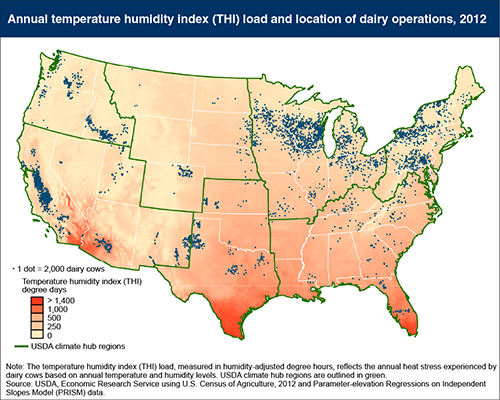

Similarly, farmers in the United States have also sought out the coolest places to dairy. Take a look at the map below. Certain parts of the country are more cow dense than others. Those areas with more cows tend to be in states with more temperate climates: California's Central Valley, Idaho, New York, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. On the other hand, there are fewer cows in the muggy Gulf Coast region in states like Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida.

Like people, animals experience heat stress when temperatures reach a certain level. Dairy cattle in particular are more sensitive to elevated temperatures, and hot weather can lower milk production and reduce the percent of fat, protein, lactose and other solids in milk.

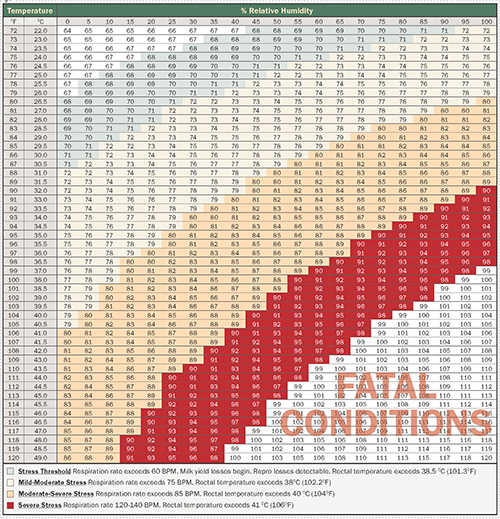

It's not just the temperature that affects cows; more often, it's the combination of heat and humidity. A measurement called the Temperature Humidity Index (THI) is used to determine the impact both heat and humidity have on dairy cattle. Research has shown that milk yield losses are already apparent when the THI reaches 68. The chart below can be used to determine the level of heat stress experienced by dairy cattle when temperatures and humidity reach a certain point.

The author is an associate editor and covers animal health, dairy housing and equipment, and nutrient management. She grew up on a dairy farm near Plymouth, Wis., and previously served as a University of Wisconsin agricultural extension agent. She received a master's degree from North Carolina State University and a bachelor's from University of Wisconsin-Madison.