You scoured the latest proofs in search of the best bulls to sire your future herd. But once the resultant heifer calf is on the ground, do you reinforce your mating decision and enable the calf to live up to the potential that was bred into it?

As task-oriented individuals, we often forget how big the "system" on a dairy really is. Mike Van Amburgh, Cornell University, believes the calf is part of a system, but the system goes beyond giving it colostrum, keeping it alive and getting the calf weaned. It has to be a proactive, not passive, system that goes beyond survival to weaning.

During a World Dairy Expo educational seminar, Mike Van Amburgh, Cornell University, discussed the factors that create the quality heifers, and later on cows, that we all want.

Challenging the status quo

In the late 1990s, Van Amburgh challenged the industry with one basic question: Why do we limit the nutrition from milk to our baby calves? Since that time, research from Van Amburgh's lab and others has shown that when we limit-feed calves, we limit their potential.

At times, limit-feeding milk is akin to starvation. "Starvation is not a hard problem to solve prior to the event," quipped Van Amburgh.

This is especially critical in northern climates where temperatures dip and strong winds blow during the winter months. "In these extreme situations, calves end up using what little tissue they have to stay warm," Van Amburgh noted.

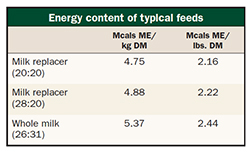

"We have to stop talking about how many bottles we feed per day and start talking in the currency that the calf understands. That's Mcals (megacalories) of energy and grams of protein," noted Van Amburgh. To solve the problem of starvation, we have to move to this currency.

As can be seen in the table, there isn't much difference between a 20/20 milk replacer and a 28/20 - you just have to feed more of it. The dam's milk, meanwhile, has a bit more energy in it due to its higher fat content.

"You see immediately that the 20/20 we've had as an industry standard is not what mom's milk is. I still hear this: ‘I went to waste milk, and my calves are doing really well.' It's because it has more nutrients. That's the way it's supposed to be," he continued.

More milk leads to more milk

To date, there are 13 studies that have proactively looked at early life nutrition and milk yield. Two of these studies saw no milk production advantage with a high plane of preweaning nutrition. These studies also did not observe differences in growth rate by weaning. The remaining 11 studies all observed improved milk production when calves were provided with enhanced nutrition preweaning.

"If you have a real difference in growth rate prior to weaning, you should be able to detect a milk yield response between 1,000 and 3,000 pounds in the first lactation," noted Van Amburgh. "You're twice as likely to get more milk later on if you feed them better as a calf," he continued.

When averaging the 13 studies, Van Amburgh's group found that, for each pound of average daily gain that's achieved prior to weaning, you should get 1,500 pounds more milk.

"If you feed a 20/20 milk replacer at a rate of 1.25 pounds per day (with no stress conditions), at best calves will achieve 0.4 pound of gain per day. If you feed 2.2 pounds of a 28/20, you should get at least 1.6 pounds of gain per day," noted Van Amburgh.

"With a 1.2 pound difference in average daily gain, you'd expect the heifers with better rates of gain to make at least 1,800 pounds more milk," he continued.

"In this evaluation, 22 percent of the variation in first-lactation milk yield was attributable to the calf's growth rate prior to 49 days of age. Genetic selection for milk yield only accounted for 7 percent," added Van Amburgh.

In a nutshell, selection for our primary trait (milk production) accounted for only one-third as much of the variation in milk production as the plane of nutrition did.

"Genetic selection yields about 200 pounds of milk. Genomics has changed that, but, historically, preweaning calf nutrition has yielded somewhere between four and eight times more milk in lactation than genetic selection," he added.

Calves are intake sensitive

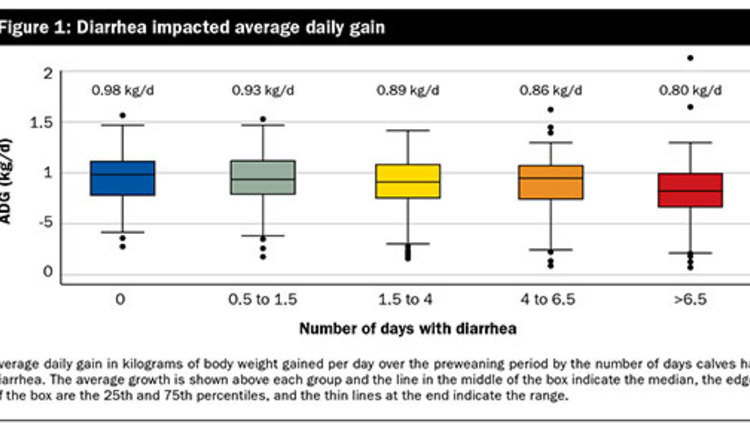

The mean response in the data from the Cornell dairy herd was 850 pounds for every pound of average daily gain. Part of this yield difference when compared to the meta-analysis average of 1,500 pounds can be explained by treatment incidence.

Cornell's standard operating procedure indicates that, if a calf has a respiratory disorder, it must be treated with antibiotics. Calves that were treated made 623 pounds more milk per pound of average daily gain. Untreated herdmates doubled that, making 1,400 pounds of milk per pound of average daily gain.

"Calves that didn't have a respiratory disorder didn't go off-feed, and ultimately made more milk. The calf that didn't feel well and went off-feed made less milk. Early on, calves are extremely sensitive to intake," he noted.

An environment that minimizes respiratory incidences and treatments is essential. Each respiratory incidence will detract from milk production when that heifer enters adulthood.

What this ultimately means is that, if we're going to select animals for a greater genetic capacity for milk production, we have to treat them like that.

"But we just don't do that. That has been our failing as an industry. We're focused on low cost. This is probably one of the areas, just like the transition cow, that being the lowest cost isn't the best and won't lead to the best possible outcome," added Van Amburgh.

"We know that enhanced lean growth during the neonatal period has a long-lasting implication for milk yield, and the impact of nurture is up to seven times greater than nature. We need to make sure we reinforce each heifer's genetic capacity with the management and nutrition that allow it to happen," he concluded.

160225_117