The authors are all with Michigan State University. Cullens is the director of South Campus Animal Farms, Weber-Nielson is an associate professor, and Van Soest is a master’s degree student.

A relatively new trend in calf raising is feeding transition milk to calves in early life. Dairy producers have long understood the importance of quickly providing newborn calves with colostrum soon after birth; however, new research is showing that continued feeding of colostrum and transition milk results in long-term benefits to calves, including more growth and better health.

As the cow transitions from colostrum production to milk production, this intermediate milk is often overlooked. But transition milk is different. Not only does it contain more energy and protein than mature milk, but it also has immunoglobins and other potentially beneficial hormones and bioactive components.

Although there is no uniform definition, milkings 2 to 5 after calving are generally considered transition milk. Since transition milk is not saleable (the Grade A milk requirement is to withhold the milk from sale until such a time that the colostrum is no longer present), farms that are able to capture and segregate this milk can reap the benefits to calf health with little to no out-of-pocket cost.

The feasibility of separating, saving, and feeding transition milk will depend on how many calves there are and the current feeding system. For producers already feeding whole milk to calves, separating out milkings 2 to 5, storing the milk, and feeding it to the youngest calves will take some minor management tweaks and another storage tank.

The logistics might be a bigger hurdle for producers that put calves on milk replacer immediately after colostrum feeding. An easier solution, although more costly, would be to add colostrum replacer powder to the milk replacer or whole milk for selected calves.

Fewer sick calves

A 2014 study published in the Journal of Dairy Science found calves fed two or four feedings of transition milk (milkings 2 to 6) after the initial single feeding of colostrum had improved visual health observations that were recorded twice weekly. Calves fed transition milk were less likely to receive a worse eye or ear score (for example, more eye discharge or a pronounced ear droop). They also had lower odds of being assigned a worse nasal score during the study period relative to calves that received no transition milk. Observations were collected the first 12 weeks of life for heifer calves and the first three to four weeks of life for bull calves.

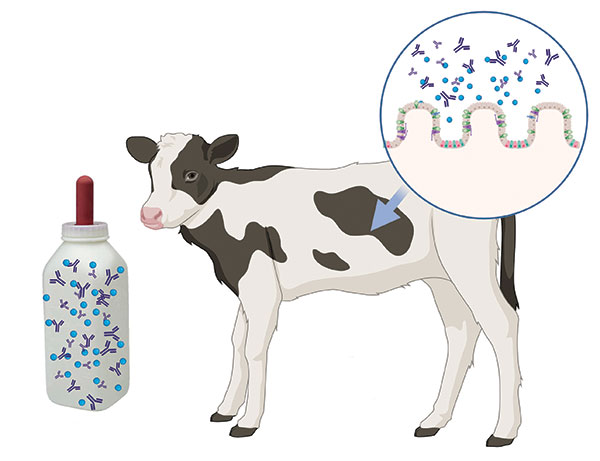

All calves in the study achieved adequate passive transfer of immunity following the initial single colostrum feeding, and transition milk feeding did not impact calf IgG concentrations. This points to the many other nutritional and immune factors provided by colostrum and transition milk that could influence short- and long-term health. For example, the localized effects of antibodies within the gut may protect against entry of pathogens, or other factors present may have immune-enhancing effects unrelated to immunoglobulins.

More growth before weaning

These unanswered questions led our research group at Michigan State University on our own endeavor. Our experiment included feeding transition milk or extended colostrum replacer on a commercial dairy farm previously feeding milk replacer immediately following colostrum. In this study, transition milk was collected from milkings 2 to 4 after calving, pooled, frozen, and batch pasteurized before being transferred into individual feeding bags and refrozen.

Calves were randomly assigned to three different diets for nine feedings (three times daily) immediately following two feedings of colostrum replacer. Treatments were milk replacer, transition milk, or milk replacer plus colostrum replacer.

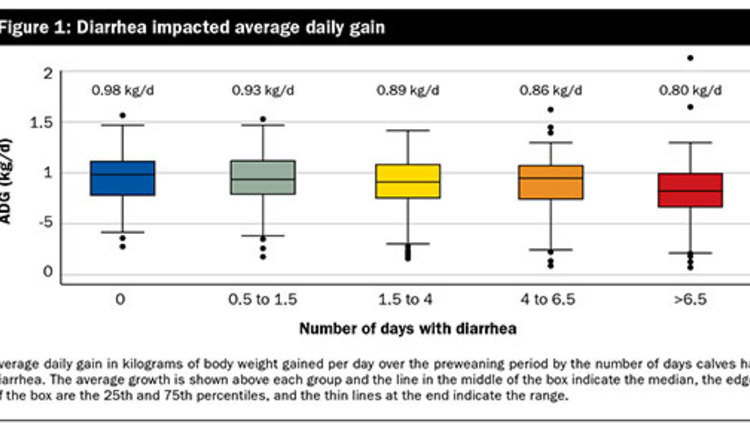

From birth through weaning, calves fed transition milk and milk replacer plus colostrum replacer gained 6.6 pounds more total body weight than those fed milk replacer (0.12 pound per day over 56 days). Extra metabolizable energy (using NRC 2001 equations) from the higher solids in transition milk only accounted for 1.5 pounds of the additional gain of calves fed transition milk compared with milk replacer. Treatment did not alter daily health scores for ears, eyes, or feces on this farm, which had excellent calf health and no off-farm transport of young calves.

While this initial study did not dive further into the reasons that transition milk confers these benefits, a follow-up study that hasn’t been published yet showed that unpasteurized transition milk stimulates development of the digestive tract through cell proliferation (increasing cell numbers). This ultimately expands small intestinal surface area and potential nutrient absorption in the first week of life. Calves not receiving transition milk may be missing out on the opportunity for greater gut development and improved health.

Benefits down the road

To justify the feeding of transition milk on farms, it must be feasible, economical, and beneficial. Dairy managers should consider the value of additional weight gain and better calf health in their operation, keeping in mind the evidence that improved early life growth and health may result in greater lifetime milk production. An analysis published in the Journal of Dairy Science in 2012 found that for every 1 pound of preweaning average daily weight gain, milk yield was 1,113 pounds higher in the first lactation.

Research on optimal nutrition for calves after the first colostrum feeding is limited. On farms where feeding transition milk or supplementing with colostrum replacer is feasible, improved health and faster growth in calves may be achieved by implementing this practice.