A dairy feeder calf is a young (1 to 14 days of age), often male, calf that leaves the dairy farm to enter the red meat industry. In Canada and the United States, these calves are most often destined to enter as veal or dairy beef.

The health status of dairy feeder calves remains largely unknown in North America, with the last studies to describe mortality of dairy feeder calves being completed more than 20 years ago. However, it is estimated that calf mortality in dairy beef and veal remain high despite significant advances in calf care and health.

Based on this concern, a project underway at the University of Guelph is shedding new light on the current state of dairy feeder calf health. The study has demonstrated that a significant number of dairy feeder calves are entering red meat production units with significant health abnormalities.

One-third have issues

Of the over 4,000 calves that have been screened upon arrival at a milk-fed veal facility, 38 percent were identified as abnormal. Some of these abnormalities are associated with mortality in the first 21 days after arriving at the barn.

A significantly enlarged navel with heat, pain, or moisture was found in 6 percent of the screened calves, and these calves had a four times greater chance of dying as compared to calves with no navel infection. One out of every five calves was found to be depressed or dull, and these calves were two times more likely to die compared to a bright, alert calf. A sunken flank was present in 29 percent of calves, and these calves had a three times greater chance of dying in the first 21 days compared to calves without a sunken flank.

Overall, if the calf was identified with any of these abnormalities through the screening process, it was two times more likely to die in the first 21 days after arrival. The conclusions that can be drawn from the study so far are that calves can be identified on arrival as high risk for mortality, and consequently there are several areas to focus on for prevention of mortality and to improve overall calf welfare.

The first caretakers

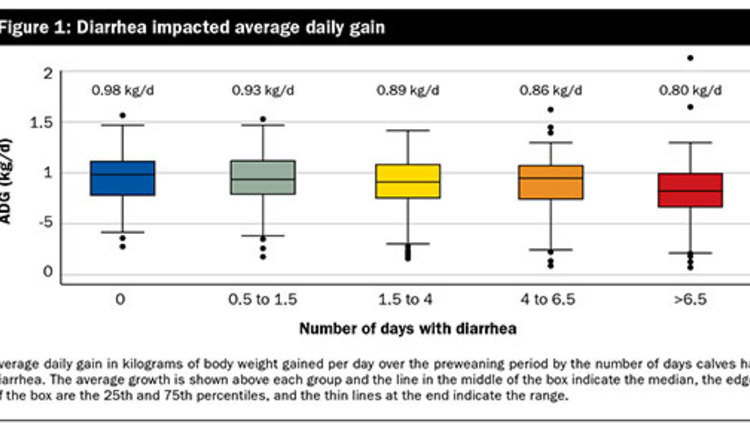

Dairy beef and veal operations rely on dairy producers to provide the necessary care for newborn dairy feeder calves. As is well-described in the literature, care in the first week of life is essential to minimize the impact that calfhood diseases have both short and long term. It is crucial for everyone — dairy farmers, dairy beef producers, and the veal industry to work together to prevent these diseases, thereby ensuring the economic viability of dairy feeder calves.

Prevention of disease begins at calving. As bull calves are usually larger in stature, they more often present difficult calvings. Birth trauma significantly compromises calf vigor and amplifies the risk of stillborn calves and neonatal calf mortality. It is crucial to monitor calvings, know when and how to intervene and when to get professional assistance to not only improve calf vigor but also reduce the number of stillborn calvings.

Pain control for calves may also be needed to alleviate the distress associated with difficult calvings; this results in faster rising following birth and enhanced consumption and absorption of colostrum. The outcome is reduced calf sickness and mortality.

A clean calving environment with an ample amount of bedding is another important piece of maternity care. It will help calves withstand cold stress in the wintertime, reduce the amount of disease pressure by keeping the navel clean, and limit the chance of calves ingesting manure.

Colostrum is an essential component of newborn calf care. In Canada and the United States, the majority of male dairy calves (92 percent and 96 percent, respectively) receive colostrum according to national survey data. Despite the high percentage receiving colostrum, there are several differences in the collection and feeding of colostrum between heifer and bull calves.

Bull calves were more likely to receive colostrum significantly later after birth (4.6 hours versus 3 hours), and producers relied on the bull calf suckling colostrum from the cow more often versus heifer calves. Bull calves were more likely to receive contaminated colostrum in another published study.

During colostrum collection it is crucial to ensure a clean process as bacterial contaminants can lead to disease and reduce absorption of colostrum. Correcting these differences regarding colostrum collection and feeding between bull and heifer calves will have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality in dairy feeder calves.

During the first few weeks, nutrition and housing are critical components to maintaining bull calf health. Feeding higher amounts of milk (6 liters or 1.6 gallons per day or greater) will help reduce the weight loss in the days following birth. This will result in heavier calves being sold to veal and dairy beef producers with more energy reserves to cope with the stresses associated from moving to a new facility. Having a well-bedded, draft-free, clean and dry area for bull calf housing will create a comfortable environment with an improved ability for the dairy feeder calves to respond to disease challenges.

A high stress time

Transportation of dairy feeder calves is extremely stressful as these young animals are moving from a comfortable and consistent environment into an extremely variable environment where they are mixed with many unknown calves. Transportation of young calves can result in dehydration, muscle damage, depletion of energy reserves, and greater mortality rates. Of course, this varies depending on age at transport, length of transport, and weather conditions.

To counteract some of the challenges with transportation, ensure calves are dry, well-fed, and able to stand without assistance. Wash and disinfect the transport vehicle and ensure the floors have ample bedding to provide good footing and absorption of manure and urine. Likewise, appropriate preparations need to be made to maintain thermal comfort during the move. Lastly, minimize the distance calves are transported and ensure that there are qualified personnel trained in suitable loading and unloading procedures.

Dairy feeder calf raisers also can provide benefits to the dairy producers from whom they source calves. They can supply valuable information regarding the health and survival of calves originating from a particular dairy farm as an indicator of the success of that dairy producer’s calf rearing program. The veal and dairy beef industry also could offer incentives to calf suppliers based on colostrum status and mortality rates, which in turn could motivate dairy producers to improve their management of bull calves. When all of these industries work together, calf health and welfare will significantly improve with benefits accruing for all involved.