The world dairy markets offer a bad-news/good-news story for U.S. dairy farmers.

The international milk powder markets plunged last summer to prices that hadn’t been seen in more than a decade. In addition, world prices for cheese, butter, and whey hit seven-year lows. However, strong domestic consumption insulated U.S. farmers from the world market slump more than any other export supplier.

In fact, it was farmers in New Zealand, Australia, and the European Union who “paid” to rebalance the world market after 2013 to 2014 excesses.

The markets finally recovered in the second half of 2016. This new year looks to be improved, with international prices closer to historic averages (except skim milk powder, which is expected to lag).

A reshaped U.S.

In the oversupplied, highly competitive world that emerged in the second half of 2014, U.S. exporters retreated. Our export volumes shifted into a lower gear — about 15 percent below our peak 2014 levels — after expanding steadily for more than a decade. We continue to push out nonfat dry milk/skim milk powder (NDM/SMP) and high-protein whey products, but we’ve lost sales of cheese and dry whey at the margins, while shipments of butterfat, whole milk powder (WMP), and milk protein concentrate (MPC) have fallen to negligible levels.

For a 16-month period in 2013 to 2014, we exported more than 16 percent of our milk solids production. This year that figure is about 14 percent, as the domestic market has offered more attractive returns for growing U.S. production.

And thus the conundrum. For a decade, thanks to strong world markets, the U.S. dairy industry expanded on the back of exports. But our ability to dodge the pain of historically weak world markets in the last two-plus years has made some folks forget that if the U.S. dairy industry is going to continue to expand at the desired rate in the years ahead, export business is almost certainly going to have to be part of the picture.

More balanced

While we’re unlikely to see another sellers’ market boom in the next five years, global supply and demand should be closely aligned, according to the U.S. Dairy Export Council’s new “2021 Global Demand Forecast.” In sum, global demand is forecasted to grow 3.6 percent per year, about half a percent below the 10-year average, while supply growth will just manage to keep pace. The markets will remain competitive — as we’ve seen in the post-boom period — and the main U.S. competition will come from Europe.

China will remain the key driver of global demand, the report concludes. We forecast 6 percent annual growth in imports, nearly the same annual volume increase seen in the previous decade, when growth off a smaller base averaged 14 percent annually. With this, China is expected to account for about one-fourth of the growth in global import demand in the next five years.

The other two large importing regions — Southeast Asia and the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) — are on track for ongoing expansion. Imports from Southeast Asia are forecast to see 3.4 percent annual growth through 2021, the report says, as growing populations and spending power drive demand for foods that use dairy ingredients. This is a slightly faster rate than the 10-year average. Meanwhile, imports from the MENA region ( 3.2 percent per year) are expected to face headwinds from lower oil revenues.

Small . . . but big

Mexico’s import volume is just one-third the size of the MENA region, but the United States’ largest overseas customer is projected to raise imports by at least 3.6 percent per year over the next five years. Japan and South Korea — with combined imports equal to Mexico — are expected to see slower growth in the years ahead, about 2.8 percent annually, as populations in those countries continue to age.

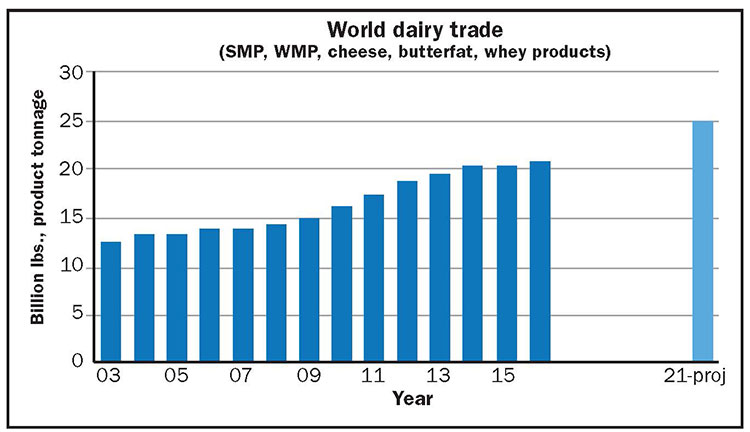

Add it up and import demand to 2021 is forecast to increase by more than 5 billion pounds, milk equivalent, per year — in line with the annual growth seen over the last decade. The U.S. dairy industry remains positioned to capture a significant portion of this growth, but suppliers will have to contend with very aggressive exporters from the European Union, the report concludes.

European milk production is forecast to expand 1.3 percent per year to 2021, creating a surplus of approximately 2.7 billion pounds of milk each year that will be sold overseas. Like the United States, most of Europe’s exportable supply will go into cheese, SMP, and whey products, creating keen competition in key markets including the MENA region, Southeast Asia, Japan, and South Korea.

Slow for top exporter

Meanwhile, production growth in New Zealand is expected to slow to less than 2 percent per year, with most of the increased output moving into WMP, while flat to declining production in Australia means less is available for export. Argentina may be able to resume a growth trajectory, but political and economic issues keep them from supplying the world market on a consistent basis. Belarus continues to expand production, but almost all of their exports are dedicated to Russia, which appears off-limits to Western competition for the foreseeable future.

In addition, none of these countries have the production capacity to meet growing demand for cheese, SMP, and whey. As a result, these are the categories in which the United States is best poised for growth. And even with EU competition, there is ample opportunity for U.S. exporters to maintain their 10-year growth rate of 7 percent annually.

Exports haven’t garnered much attention in the United States in the last two years, but even at 14 percent of our production those sales are still a critical outlet for our milk. The domestic market, recent strength notwithstanding, can’t absorb everything we produce. Therefore, the growth rate of the industry in the years ahead will depend in large part on our ability to consistently tap overseas markets.