Despite some significant headwinds, 2018 was a record year for U.S. dairy exporters. Export volume was up 10 percent from the prior year, led by all-time highs in overseas shipments of nonfat dry milk and skim milk powder (NDM and SMP), high-protein whey products, and lactose. Along the way, we grew our share of global trade against our major competitors from Europe and Oceania.

Why is this so important?

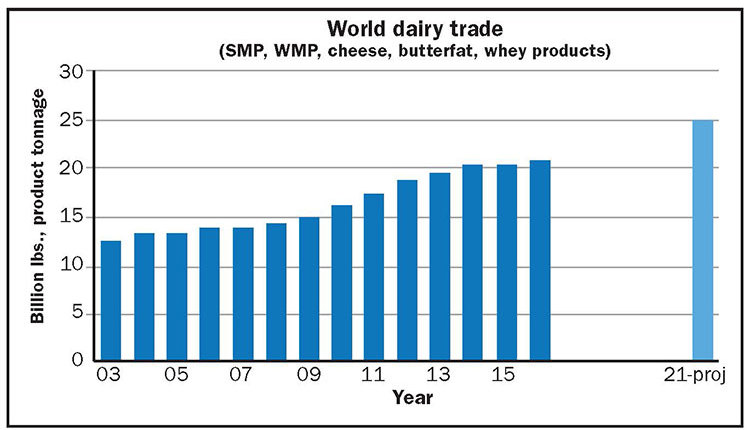

Simply put, exports support the growth aspirations of the U.S. dairy sector. For an industry whose fortunes rose and fell almost exclusively on the mood of the domestic market in an earlier era, U.S. dairy exports have taken off in the last 15 years. Milk production has climbed 1.6 percent per year since 2013 (plus 28 percent overall), and exports enabled about half of that growth. Exports grew from 6 percent of U.S. milk solids production in 2003 to nearly 16 percent in 2018.

But U.S. exporters weren’t exactly taking victory laps at the end of last year. Volumes sank in the second half of 2018, attributed primarily to retaliatory tariffs on U.S. dairy exports to China (and to a lesser degree, on U.S. cheese to Mexico). Likewise, 2019 got off to a slow start as the tariffs remain in place.

Still, market conditions are improved this year after four years of surpluses. Global production growth has slowed to a crawl, EU government inventories have been drawn down, and world demand remains good. It’s the start of market rebalancing.

That’s the good news.

It doesn’t necessarily mean world prices will break out of their four-year range, though. Prices won’t be as low as they were in recent years, but barring some unforeseen shock, there are a number of drivers that will limit a significant break to the upside.

Price elasticity for dairy commodities is critical. Buyers have demonstrated that they stock up when prices are low and then back off as prices become too rich.

Global demand growth is heavily reliant on China. Import growth from China was robust in late 2018 and early 2019, but when that pace slows, there really aren’t enough other buyers in the world big enough to pick up the slack.

On the supply side, European farmers can respond quickly to higher prices, preventing markets from getting too hot. This is a big difference from the last major market boom in 2013 to 2014, when milk production quotas limited the ability of EU farmers to increase supply.

Macro factors play a key role as well. Feed is cheap, maintaining margins even at lower milk prices. The U.S. dollar has strengthened over the last year, which puts downward pressure on global prices. It’s unlikely we’ll see a major breakout in oil prices anytime soon, which constrains dairy import demand from the Middle East/North Africa region.

And yet, the opportunity to grow export volumes is as real today as it was 15 years ago. Dairy trade rose 2.8 percent in 2018, the best showing in the last five years.

Global dairy imports continue to grow for all the reasons they’ve always grown: increasing populations and incomes in emerging markets; difficulties in dairying in hot or humid climates; rising awareness of the health benefits of dairy; improved cold-chain infrastructure; and ongoing innovation in the functionality and application of dairy ingredients.

We expect trade to maintain a solid growth rate of 2.5 percent annually over the next five years. On a basket of milk powder, cheese, butterfat and whey, that’s an additional 250,000 tons of traded product every year.

Where will this growth occur?

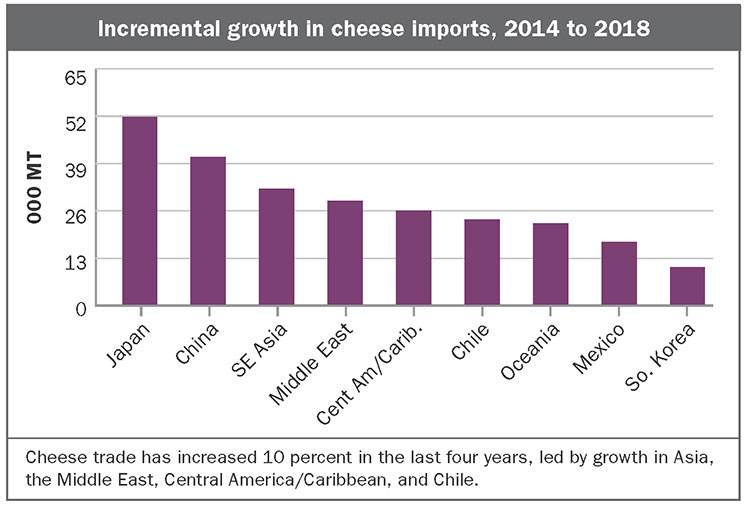

The largest-growing import markets for cheese were Japan, China, Southeast Asia, Middle East, Central America/Caribbean, and Chile over the last four years

The top-growing import markets for NDM/SMP are Mexico, Southeast Asia, China, Pakistan, the Middle East, Central America/Caribbean, and Pakistan.

The top-growing import markets for whey products are China, Southeast Asia, Oceania, North Africa, and South Korea.

WIDENING DIFFERENCES

U.S. suppliers are positioned to capture a good chunk of these growing markets, but the proliferation of trade agreements by our competitors — while U.S. suppliers suffer fallout from our own trade wars — threatens our progress.

For instance, by 2025, the EU will have preferential access for 24,600 tons of cheese to Japan, plus 15,000 tons of milk powder and butter and 8,440 tons of whey. In Mexico, our largest export market, the EU will have new access for 25,000 tons of cheese and 50,000 tons of SMP by 2025, while New Zealand, Australia, and Canada will have new access for 37,000 tons of milk powder. Meanwhile, New Zealand and Australia already have preferential access to China.

All this matters for dairy farmers, because over the last five years, less than 20 percent of the “new” milk produced in the U.S. went to products sold overseas. Growth in domestic consumption absorbed the bulk of the gains, but about 15 percent just went into inventory, which continues to weigh on the market. And, in fact, the U.S. milk production growth rate is slowing from the long-term pace.

If global trade keeps expanding as all analysts expect it to, the world will need our milk. Europe and New Zealand can’t supply it all.

But whether exports can continue to support the growth aspirations of the U.S. dairy sector will depend, in large part, on suppliers’ ability to contend against very tough competition.