The author is director of Dairy Policy Analysis, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Who would have thought that major news purveyors, like The Economist and The Wall Street Journal, would have even noticed that the open outcry pits for spot trading cheese at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange were being closed in favor of electronic trading?

But each publication ran articles in May and June, noting the recent end of an era.

Most of us have a vision of open outcry futures trading at the CME from movies like Trading Places with Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd. The spot markets for dairy products were a bit more tame than the movie, but it was somewhat similar with traders in orange, green, blue, and other colored jackets taking orders on phones and then posting the bids, offers, and sales of products on a board.

Dairy started a transition

Last December 5, the CME (previously known as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange) did a trial run of electronic trading on the spot market with nonfat dry milk. That product successfully transitioned to all electronic trading. It was followed by butter on April 10 and, most recently, cheese on June 26. The open outcry trading for dairy products is no more.

A few folks mourn the loss of the human factor and the sense of emotion when trading gets hot, but we don’t seem to see any other downside to the more modern and efficient mechanism for buying and selling a few loads of product. In fact, trading volumes are up and there are several potential benefits that are not hard to imagine.

For starters, it would be easy to add new products like whey to spot market trading. And, the trading is more scalable to longer hours, more participants, and offers greater anonymity for buyers and sellers — all desirable attributes.

Whither spot trading

The bigger question may be, “Why do we have spot trading at all?”

If we dig back into history, we find that, while cheese is thousands of years old, the first cheese factory in the U.S. was started in Wisconsin in 1841. Over the next several years, many cheese plants sprung into operation in Wisconsin, New York, and Ohio, and by the turn of the 20th century (1900) we reached the peak number with more than 3,500 cheese processors in the U.S.

At first, dealers bought cheese and other dairy products directly from plants. They would assemble their purchases from several factories but this was inefficient.

Cheese factories soon created dairy boards, which provided a place for cheese buyers and sellers to meet. These still needed to be local and small.

The next logical step was to employ the relatively new technology of the telephone in the 1880s to create “Call Boards.” A Call Board could facilitate offers and bids from interested parties by recording them on a blackboard with the sales going to the highest bidder.

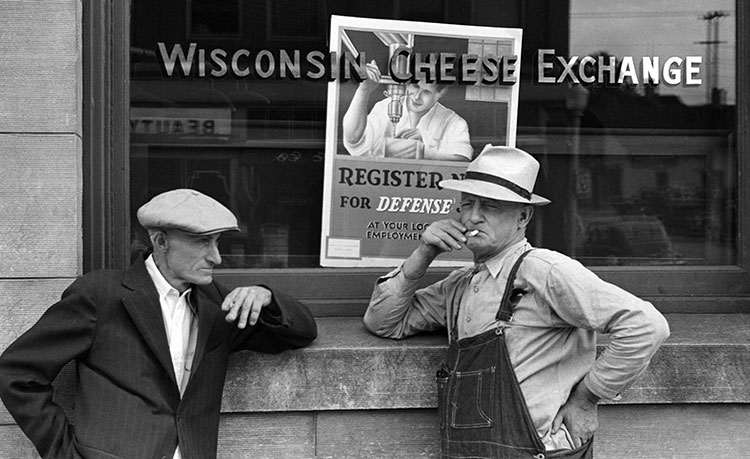

There were as many as 18 separate Call Boards in Wisconsin alone, but in 1918 the Plymouth Central Call Board of Trade was reorganized as the Wisconsin Cheese Exchange, which dominated spot trading in the state. New York also had a very active Call Board in Cuba, which functioned very much like the exchanges in Wisconsin.

In 1956, the Wisconsin Cheese Exchange was moved to Green Bay, and in 1958 it replaced the function of the Cuba Cheese Exchange as well. In 1974, the Wisconsin Cheese Exchange was renamed again as the National Cheese Exchange (NCE) and provided the spot market activity for the entire U.S.

Collateral benefit

The NCE provided valuable services for buying and selling loads of cheese. Although the sales volume was small relative to the entire U.S. cheese market (1 to 2 percent of total production), the prices discovered on the exchange also served as a beacon for national price discovery. Most activity on the exchange was motivated by the need to purchase or sell a few loads of cheese and was not the primary marketing strategy for any company.

These sales were thought to represent the marginal value of cheese and the prices could be used as a benchmark for more sophisticated marketing plans. As an example, a cheese plant and a retailer might strike a deal to sell cheese between one another for the NCE price plus 5 cents. This allowed prices to move according to a market, and it was a visible price for both parties.

The NCE became wrapped in controversy in the mid-1990s as concerns were raised about participants attempting to manipulate the market. In May 1997, spot market cheese trading moved from the NCE to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange where it exists today.

Spot markets fill voids

It is not uncommon for a processed cheese line to go down. The plant will still be receiving shipments of barrel cheese that it can’t process and must sell a car load or two quickly on the CME. Or, a butter manufacturer may have a customer who is demanding more product but the plant doesn’t have uncommitted milk or cream. They can try to procure a load of butter at the CME.

Spot markets first and foremost fill a physical need for buyers and sellers to exchange a small amount of product. Their collateral benefit is that we can observe the change of marginal values of dairy products at any point in time.

The human factor of calling out a bid or an offer and posting that on a chalkboard may no longer exist, but the need for, and the function of, spot sales continues with electronic trading. Whether it’s a meeting room, a telephone and chalkboard, an open outcry, or the internet, the dairy industry needs some form of spot trading!