Heat stress poses significant problems for the lactating cow. The extra heat produced due to greater feed consumption and metabolism makes it difficult for a cow to maintain normal body temperature. Air temperatures as low as 77° to 84˚F can cause a cow’s body temperature to rise. This results in reduced feed intake, lower milk yield, and poor fertility.

Shades, fans, soakers, and other environmental modifications have helped reduce heat stress. However, these cooling mechanisms do not usually eliminate problems completely. In some farming systems, for example grazing dairies, it is not practical to provide optimal cooling for cows.

Genetics might help minimize heat stress. The slick gene, which gets its name from the fact that animals inheriting it have a short and sleek hair coat, is actually a mutation in the prolactin receptor gene that was first described in the Senepol breed. Like the polled gene in cattle, the slick gene is dominant — inheritance of one gene copy causes an animal to display a short sleek hair coat.

The slick gene entered the Holstein breed in two separate ways — once intentionally and once by accident. Beginning in the early 1990s, Tim Olson at the University of Florida intentionally began a breeding program in which Senepol-Holstein crosses were backcrossed with Holsteins. That produced females that were nearly pure Holsteins with the exception of the slick gene. In another scenario, the slick gene also was introduced into the Holstein breed in Puerto Rico, probably when dairy farmers bred Holsteins to local cattle containing the slick gene.

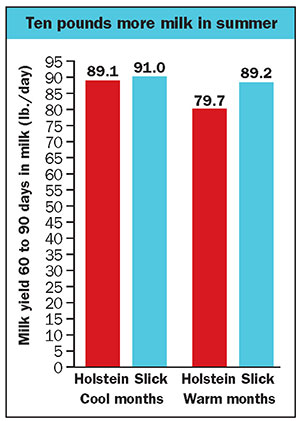

Secondly, heat stress had lower impact on milk yield among slick Holsteins than typical Holsteins. Shown in Figure 2 are results of a study at the University of Florida comparing milk yield of cows calving in cool months (October to December) and hot months (May to July). Although milk yield was similar for slick and nonslick Holsteins calving in cool months, milk yield for cows calving during hot months was greater for slick Holsteins.

Researchers in Puerto Rico evaluated differences in milk yield between slick and nonslick Holsteins throughout the year and over a 305-day lactation. Overall, slick Holsteins produced 1.2 more pounds of milk per day than nonslick Holsteins.

There is less information on reproductive function of slick Holsteins. However, available evidence indicates superior reproduction for slick Holsteins. In Puerto Rico, the calving interval for a group of slick Holsteins was roughly 15 months versus 17 months for nonslick Holsteins.

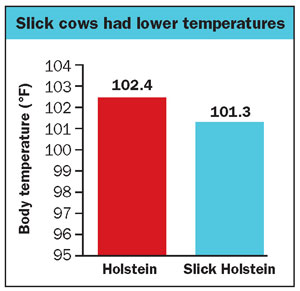

Taken together, one can conclude that Holstein cows with the slick gene have superior ability to regulate their body temperature. More specifically, when compared to nonslick Holstein cows, the reduction in milk yield caused by heat stress was less severe in slick Holsteins. There are also indications that reproduction is improved for slick Holstein cows in a hot climate.

It should be pointed out that most of the cows studied in the experiments reported here were heterozygotes — they possessed only one copy of the slick gene. Little is known about Holsteins with two gene copies.