Generally, Klebsiella are found in organic matter, including bedding and manure. Although Klebsiellacan contaminate any bedding material, the organism has an affinity for wood-based products such as sawdust and shavings. Therefore, cows bedded on fresh sawdust may be at a greater risk for mastitis caused by Klebsiella spp. Poor udder cleanliness, inadequate stall management, and damaged teat ends also present risk factors for Klebsiella infections in uninfected cows.

Klebsiella is classified as a coliform organism, as is E. coli. However, it is often more difficult to control and treat effectively than E coli. Klebsiella mastitis generally causes greater economic losses than other coliform mastitis pathogens. It can be fatal, and cows that survive the infection often are chronically infected.

Limit the spread

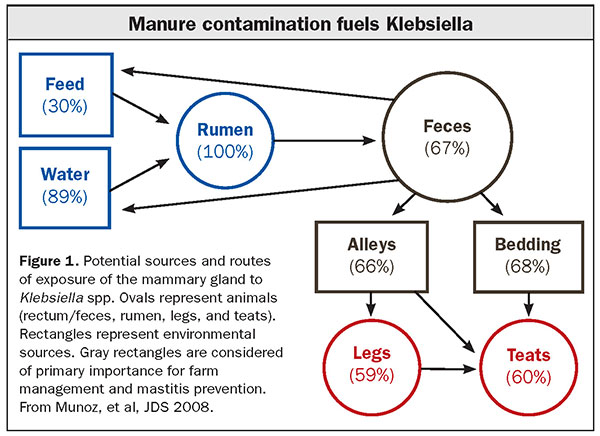

The primary method for control of Klebsiella mastitis continues to be reducing the organism in the environment and reducing an animal’s exposure to common sources of Klebsiella, those sources include those shown in the figure. It’s important to note that these sources are closely associated with contact to manure.

Adequate amounts of clean, dry bedding will help reduce contamination of cows’ teats and udders. Frequent removal of manure from cow traffic areas, such as alleys, holding areas, and around waterers, will reduce splash contamination of teats, udders, and lower legs of cows.

Historically, recommendations to lower the incidence and exposure of animals to Klebsiella in the dairy environment have included use of sand bedding, an inorganic material, over other organic bedding types such as wood shavings, sawdust, and recycled manure solids.

Costs drive choices

With high costs of bedding materials, farms are looking to different alternatives such as sand, recycled sand, or recycled manure solids. In support of earlier data, more recent research has found that inorganic bedding materials had lower initial bacterial counts compared to organic bedding materials such as recycled manure solids, recycled paper bedding, or wood shavings, particularly when these materials are wet.

However, when these studies followed the status of bedding material through use in stall areas, it found that there was little difference between the different bedding types in their ability to harbor high levels of Klebsiella and other pathogens.

All bedding materials are eventually contaminated with manure as animals continually enter the stalls. As this takes place, the bedding accumulates moisture and organic matter that promotes the growth of the Klebsiella organisms.

Additionally, recycled sand and manure solids can serve as a source of Klebsiella as organic matter and moisture accumulates during the recycled life of this material. Any bedding material can quickly become contaminated in the stall area with mastitis pathogens shed from fresh manure. Researchers at Quality Milk Production Services have found that fecal shedding of Klebsiella can occur from healthy animals.

Alleyways and holding pens have been identified as additional high-risk areas for Klebsiella exposure. Manure will splash onto the legs and teat skin as cows travel through the barns. It is important to reduce this exposure by keeping alleyways clean and dry.

Premilking teat disinfection can reduce bacterial load on the teat end prior to unit attachment. For herds with animals that have very poor lower leg and udder hygiene scores, the bacterial challenge may be too great to overcome the heavy contamination and exposure to organisms in the manure.

Measuring the impact

In a 2011 Cornell University study of seven New York Holstein herds, researchers looked at the effect of recurrent episodes of clinical mastitis during different lactations on mortality and culling. Infections due to gram negative pathogens such as Klebsiella had the greatest impact on milk yield and mortality losses when infections occurred as a second mastitis case for first-calf heifers and as a third case for older cows. Gram-negative mastitis cows were more likely to die than cows with gram-positive bacterial mastitis infections after the first two incidences of mastitis.

A second Cornell study in 2013 found that among first-lactation cows, the presence of a first clinical mastitis case generally exposed cows to a greater risk of mortality in the same month. The effect of Klebsiella infection on milk production was greater than that of other mastitis pathogens in this study, including E. coli. The second or third occurrence of clinical Klebsiella mastitis resulted in an even greater risk of mortality in mature cows.

Chronic infections

Cows that survive an acute case of Klebsiella mastitis often become chronic cases. They are usually culled due to persistently high cell counts, recurrent clinical mastitis, and/or reduced milk production.

Efforts to develop an effective vaccine to reduce the effect of Klebsiella mastitis are being pursued. Research has also suggested that ongoing use of the core antigen E. coli vaccine (J-5) may reduce the severity and incidence of Klebsiella mastitis.

Some success treating mild cases of clinical mastitis has been achieved with intramammary ceftiofur.

Cleanliness is key

The key to controlling Klebsiella mastitis is to reduce its prevalence in the total environment of the cow and reducing exposure of cows to sources of environmental pathogens.

Choosing cleaner materials such as sand for bedding is one control factor; maintaining a clean, dry facility with frequent removal of manure that reduces splash on legs, udders, and teats is key to reducing the prevalence of Klebsiella in the environment and the risk of exposure.