The authors are with Quality Milk Production Services, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

A new bug is gaining ground on our farms. This summer, two questions became commonplace from many of the farmers whom we work with in the Northeast: “Why are so many of our cultures coming back Klebsiella, and what can we do to stop this?”

Although we are not entirely clear on the reasons, Klebsiella has been on the rise over the last number of years. In fact, for many farms, it is now the dominant gram negative or coliform mastitis that they deal with.

Klebsiella’s characteristics

Among coliform bacteria known to cause clinical mastitis, Klebsiella generally causes the greatest losses to United States dairy producers in terms of milk production loss and cow mortality rates. Klebsiella intramammary infections (IMI) also can be persistent, causing a long duration of infection in the mammary gland.

Conventional antibiotic treatments have low success rates, further contributing to infection persistence. Research also has suggested that some strains of Klebsiella and other mastitis pathogens traditionally classified as environmental may be evolving into host-adapted and potentially contagious strains. Much work is currently being done to figure out why Klebsiella causes such severe mastitis.

Also, research is looking for clues as to why it is on the rise and how it can persist in the cow’s udder. Some of this work is comparing Klebsiella strains commonly found in the environment to those strains that cause chronic mastitis to look for differences that might explain how it avoids the immune system.

Compared to other coliforms

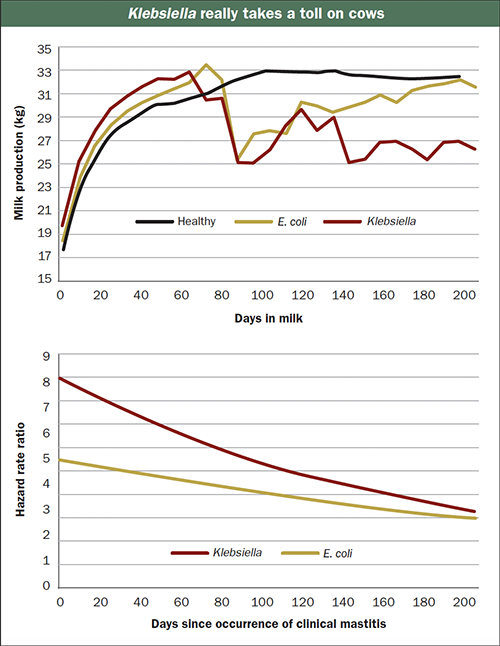

Differences in the pathogenicity of E. coli, Klebsiella, and Serratia as mastitis pathogens have been noted. These differences include a longer duration of infection for Klebsiella and Serratia compared to E. coli. Also, Klebsiella mastitis cases appear to be the most severe, followed by E. coli and then Serratia.

Klebsiella mastitis occurs more frequently in herds that have a low bulk tank somatic cell count (SCC) than in herds with medium or high bulk tank SCC. The duration of milk production loss was substantially longer in cases of Klebsiella compared to clinical cases due to E. coli.

Similarly, the risk of culling was substantially greater in cases of Klebsiella mastitis compared to E. coli. All of this adds up to the conclusion that Klebsiella is definitely a bad mastitis bug that needs to be prevented if possible.

What about prevention?

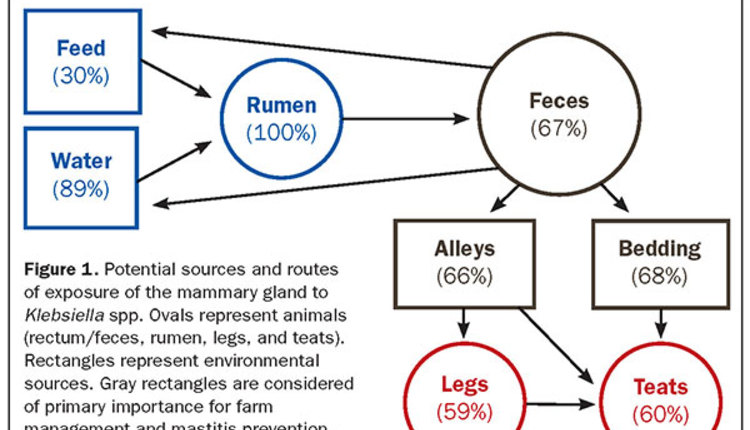

Classically, Klebsiella is considered to come from environmental sources. The work by Marcos Munoz and colleagues clearly indicates that the primary source of Klebsiella on most farms is from cow manure.

This means that the focus of the prevention efforts needs to keep manure away from the teat ends of cows. This sounds relatively simple but can be a real challenge to achieve in many farm situations. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to go through all the risk factors that we commonly see, we would like to lay out a few of the most critical areas to consider that were present on farms we investigated this summer.

On many farms this summer, stall and bedding management became a large risk factor for Klebsiella outbreaks. Poor cow positioning in the stall can lead to accumulation of manure in the back of the stall. This can exacerbate the levels of Klebsiella in the bedding even in herds using new sand.

Relying on your employees to remove all this manure at each milking is a tall order that does not always happen based on our observations. If cow positioning is a problem on your dairy, investigate if it is related to bedding levels, stall or loop dimensions, or absence of a brisket pipe, and then work to correct it. Also look for areas of manure accumulation where cows walk. This deeper manure can easily splash onto teats and udders depending on the speed that the cow is moving.

The milking center also should be a focus area as the teat canals are open during this time. Start by evaluating teat end cleanliness prior to unit attachment; this situation was a significant risk factor on dairies with Klebsiella challenges this summer. Teaching your employees how to properly clean the teat end can have large benefits in terms of reducing the risk of mastitis.

The milking routine, vacuum, and pulsation levels also can affect the health of the teat end in both the short and longer term and on some farms, this was a problem. Pre- and post-dip coverage are also a critical component of reducing the risk of mastitis and maintaining healthy teat skin.

Another large risk factor that we identified on multiple farms this summer was the excessive use of water in spraying deck manure toward cows that had just exited the parlor stalls. This practice aerosolizes the mastitis pathogens in manure, including Klebsiella, and sends them toward the teats and udders of these cows.

Simply using a squeegee or scraper on the deck to move manure away from the back leg area works well. Between groups when no cows are present, a more thorough job can be done with a hose if necessary.

Look at precalving housing

A third area to evaluate is the dry off procedure and dry and prefresh cow housing. We have been doing dry cow procedure audits as part of a grant, and it is an opportunity area for improvement on many dairies.

Employees need to clean the teat ends better on many dairies prior to dry treating. Employees should actually look at the gauze that they have used to wipe the teat end. If there is any manure present on it, they should take another gauze and wipe the teat again. Employees also need to control the tip of the syringe better after the cap is off to ensure its cleanliness.

Although it is not that common, we have also seen Klebsiella occur as a predominant strain or contagious-like phenomenon. We covered this situation and how to handle it in our May 2021 Hoard’s Dairyman article on page 292, “How to get to the root of pesky environmental mastitis.”

We hope that this article has given you some background information on Klebsiella mastitis and some ideas for what to look for if you are having a problem with it on your dairy. It is definitely a bad bug and one to be prevented if possible.