Do you scratch your head on pregnancy check day and wonder why you did not get as many cows pregnant as you desired? Do you ask yourself how other farms are achieving better 21-day pregnancy rates than you?

You are not the only one with similar questions. Let’s go back to square one and examine reasons why some farms are achieving high 21-day pregnancy rates. It boils down to great transition programs and healthy cows!

In a recent study, we examined the health and activity characteristics of 160 Holstein cows and their relationships to early postpartum ovulation, pregnancy at first A.I., and milk yield. Cows were classified as healthy or unhealthy, having been diagnosed with at least one disease during the first 60 days in milk. Those diseases included milk fever (1.9%), lameness (3.1%), digestion (17.4%), mastitis (3.1%), calving problems (6.2%), ketosis (11.9%), and metritis (18.8%). In the study, 68 cows had a disease condition, while 92 cows were classified as healthy.

Of cows diagnosed with disease, 48.5% had only one disease; 35.3% had two diseases; and 16.2% had three or more diseases. Five cows (3.1%) had twins and nine cows (5.6%) retained their placenta for more than 24 hours. Forty-six cows (28.8%) had abnormal milk at least once during the first 60 days in milk, but only five of these cases (3.1%) were treated with antibiotics.

Body condition

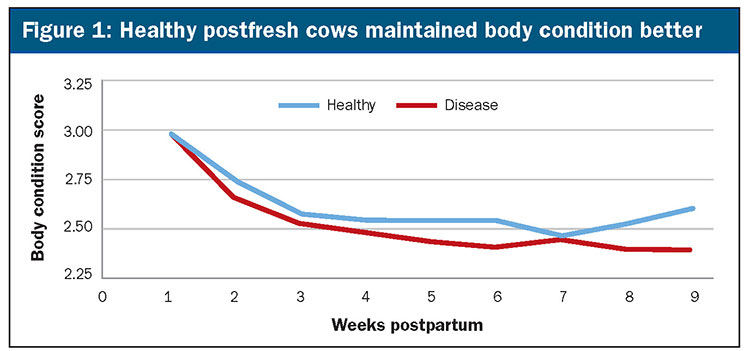

Healthy cows began to regain lost body condition about the time they were first inseminated at 70 to 76 days in milk (see Figure 1). Maintaining adequate body weight and body condition starts during the previous lactation before cows are dried off. Lactating cows are much more efficient in converting nutrients to body condition when they are in milk than when they are dry.

Examining body condition scores in cows during late lactation will tell you if your cows are too thin or too fat. Cows should go into the dry period with good body condition and be fed to maintain that condition until calving time.

Ideal body condition should be in the 2.75 to 3.00 range (1 = thin and 5 = fat) at dry-off and at calving. Cows that lose too much body weight and body condition during early lactation do not transition well into lactation and are likely candidates for multiple diseases.

Of healthy cows in the study, 54% ovulated before Day 33 postpartum. The odds of cows ovulating by Day 33 were 52% less for cows with a disease than those for healthy cows. Average days to ovulation were more than eight days earlier for healthy cows. Early ovulation by Day 33 was impacted negatively by ketosis (15.8%), metritis (30%), and digestive issues (28.6%).

A number of metabolic measures were assessed at calving and on Days 3, 7, and 14 after calving. Earlier ovulating cows had:

- Lower body temperatures

- Lower concentrations of free fatty acids (measure of fat tissue metabolism)

- Lower concentrations of ketones (measured as beta-hydroxybutyrate, reflecting the liver’s inability to metabolize completely free fatty acids to produce glucose for milk synthesis)

- Less inflammation (measured by an acute phase protein that is elevated when inflammation and infection occur)

Health and pregnancy rate

Most of the studies in the scientific literature during the past several decades demonstrate that cows ovulating and displaying early estrus after calving are more fertile. A few studies show that when health of transition cows is improved, milk yield is greater, but pregnancy rate at first A.I. is not always improved.

This was the case with our study in which timed A.I. (ovsynch but no presynch) was applied. We found pregnancy rate at first service did not differ between cows having disease and those that were healthy.

Specific diseases had little impact on pregnancy rate at first A.I. Cows with ketosis, metritis, and digestive issues had pregnancy rates near the average for all cows. We believe good management and treatment of diseases by our dairy team prevented a further reduction in first A.I. success.

Health and milk yield

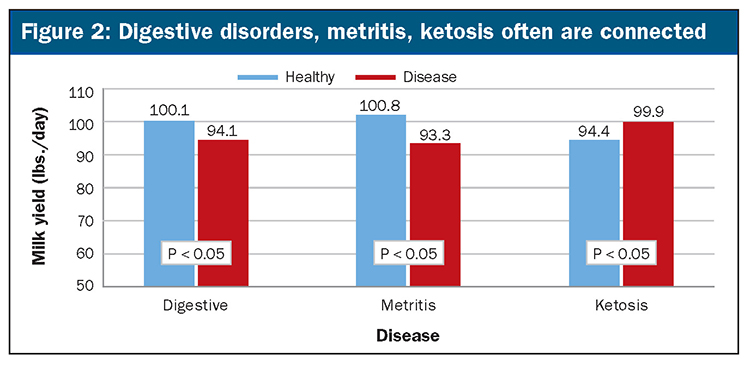

Cows with digestive disorders and metritis produced less milk, but cows with ketosis actually produced more milk than healthy cows during the first 14 weeks of lactation (see Figure 2). The reason for this oddity is that ketosis is diagnosed much more often in older and higher-producing cows than in younger cows and those producing less milk.

Research demonstrates that these transition diseases often occur together. In other words, when a cow succumbs to one unhealthy event, it is more prone to have another.

For example, calving difficulty often leads to retained placenta and metritis. Metabolic disorders such as milk fever, ketosis, mastitis, and displaced abomasum are all interrelated. The silver lining is the fact that when one disorder or health issue is prevented, the incidence of other interrelated problems also diminishes.

Working with your management team and other dairy professionals, you can refine your transition program to ultimately improve health, milk yield, and reproductive success. Happy A.I. breeding!