Corn harvested for silage can be an economically efficient way to attain high per-acre yields of digestible nutrients for feeding dairy cattle. However, silage harvest leaves little crop residue to cover and protect the soil surface. If manure is applied postharvest, conditions may be susceptible to soil erosion and nutrient loss with surface water runoff.

To improve upon this situation, many farms have adopted the practice of planting a winter annual cereal crop, such as rye or triticale, as a fall-to-spring cover crop. Whether this double-crop approach to forage production makes economic sense will depend on three main factors: cereal forage yield; the value of the cereal forage, based largely on its nutritional quality; and any impact on the yield or quality of a following crop. Based on field research conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arlington Agricultural Research Station and data collected from several cooperating farms in Wisconsin, the following guidelines can be offered.

What to expect

Forage yields of rye or triticale harvested at the relatively early growth stages of boot (just prior to the seedhead emerging from the stem) to early heading will generally range from 1 to 3 tons of dry matter (TDM) per acre. This results in a somewhat high feed cost per TDM when considering seed, planting, and harvest, particularly at the lower end of the yield range.

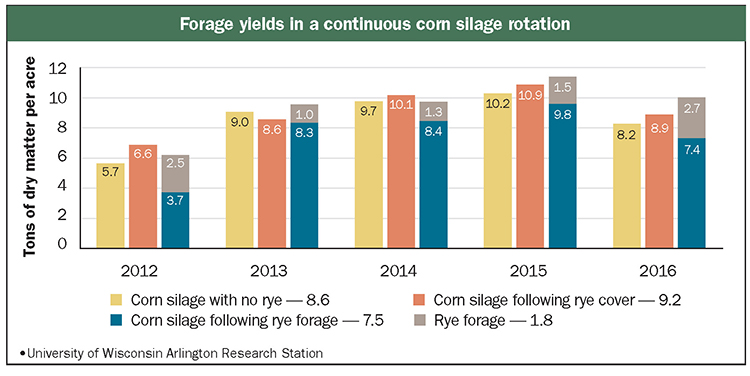

Further, corn silage yield is often suppressed when planted following rye or triticale harvested as forage. In the five-year Arlington trial, corn silage yields following rye harvested as forage averaged 13% lower. However, total forage harvested, considering both ryelage and corn silage, was equal or higher in four of the five years.

Forage quality can be variable, based primarily on harvest timing, condition at chopping or baling, and soil fertility. Relative forage quality (RFQ) averages for winter rye planted after corn silage in the Arlington trial from 2012 to 2016 ranged from 139 to 235. The average was 147 when harvested at or near the boot stage. Fermented forage samples collected from dairy farms in five Wisconsin counties in 2018 and 2019 showed average RFQ values of 109 for ryelage (36 samples) and 119 for triticale silage (eight samples).

Several methods of assigning an economic value for forages can be employed, each with limitations. Performance indexes of forage quality, such as “milk per TDM,” can be used to estimate the potential milk yield of forages included in a ration. Cereal forages, however, are more often fed to growing and bred heifers, especially if harvested at a later maturity (heading to dough stage). They offer adequate protein content and relatively high NDF content that can control intake and prevent overconditioning in pregnant heifers.

Placing a value on this type of forage may be less straightforward. One approach is to use a current market value for hay of comparable nutritional quality. In several states, this can be estimated from quality-tested hay auction reports. Again, this method has limitations as the cereal forage may have unique attributes not inherent in most hay on the market.

The table compares annual costs of production against the estimated market value for corn silage and ryelage based on yields measured in the Arlington trial and rye forage quality data collected from Wisconsin farms. At an assumed yield of 2 TDM per acre for rye forage, the cost per TDM is relatively high compared with corn silage, and gross return is low. However, adding gross returns from both the rye forage and the following corn silage crop provides an overall economic advantage in spite of the 13% corn silage yield loss. If the ryelage yield was only 1 TDM per acre, however, economics would not favor adding rye as a forage crop.

When it comes to best management practices for winter cereal forages, one must optimize economic and environmental objectives. Set a yield goal of 2 to 3 TDM per acre. Plant by mid-to-late September in southern Wisconsin, earlier as one goes north, to optimize overwinter cover, spring forage yield, and earlier spring harvest. Avoid planting delays caused by manure application.

No-till planting is preferred to minimize soil disturbance and save time. No-till planting into manure-injected fields tends to work well. Plant 90 to 110 pounds of tested and tagged seed per acre for forage or 60 to 80 pounds per acre if intended only as a cover. Provide 60 to 70 pounds of nitrogen (N) from fertilizer or manure for optimal forage yield and quality. Determine that planting rye or triticale for forage is allowed according to the required rotation interval for herbicides used in the preceding corn crop. Plan ahead as herbicide options may be limited.

Harvest cereal forages at the boot to early heading stage for optimal quality, particularly if intended for lactating cows. Regardless of animal class, err on the side of early harvest with a good weather window to reduce the risk for forage quality reductions caused by a weather delay.

The optimal harvest window is very narrow, often three to five days or less. Avoid chopping and ensiling at moistures above 70% to prevent fermentation problems. Lay a wide, flat windrow for drying. Ash content can be high with cereal forages. Take care when harvesting to minimize contact of the forage with soil and manure.

Also, avoid feeding to dry cows or heifers within 30 days of calving due to potentially high potassium (K) levels. Test the forage with wet chemistry analysis for mineral content and consult with a nutritionist on the results.