Alright, I might live to regret the following article. U.S. milk production came in much lower than forecast for January. Before the February 23 release from USDA, I was expecting production to be up 3.1%, instead it came in at just 1.6%.

Cow numbers were close to forecast with farmers still expanding the herd, but production per cow shifted from running well above trend in the second half of 2020 to well below trend in January. Many of the dairy team members here at StoneX think the USDA number may be wrong and will be revised higher based on two observations. Those include the anecdotal comments we’ve heard from cooperatives during January and February and the big discount that spot milk loads. Those are fair points.

Spot milk loads were trading at $8 under prevailing Class III prices makes sense when you’re talking about 3%-plus growth in production along with weak demand. That kind of discount makes much less sense at just 1.6% production growth.

However, those discounted milk loads are mostly in the Upper Midwest (UMW), and production in the region was still running 3.9% above last year in January, which isn’t much of a slowdown from 4% in December and 4.2% in November. Production growth in the South Central and Corn Belt also remained strong as well.

So, it’s possible there is a significant oversupply of milk in the Central U.S. which is depressing prices in the region, but production growth on the coasts looks weak. Although we’ve even heard anecdotally that production in California was/is stronger than what the USDA estimated for January (down 0.7%).

Making less milk?

If the USDA revises up their January estimate, the rest of this article is going to look stupid. I’ve always heard that dairy cows don’t have on/off switches, but there is mounting evidence that the farmers, when properly incentivized, can collectively dial up and down milk production quickly.

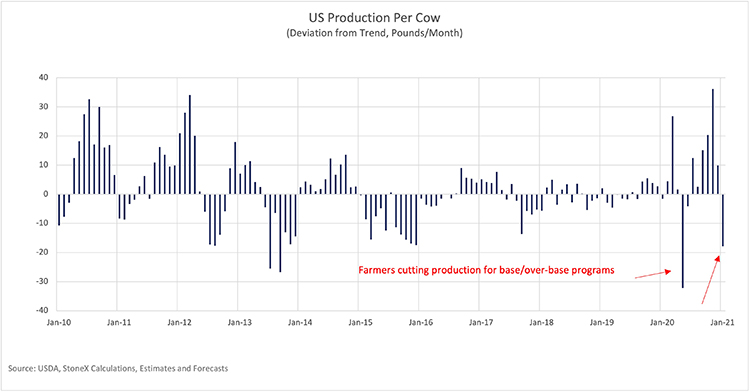

Cooperatives and milk buyers watched spot cheese and butter prices crash in late 2020 and sent out warnings to their farmers and some of them have likely tightened their base/over-base programs. I think that is the reason milk production turned out so weak for January. Even if January is eventually revised up, you can see the dramatic cuts to production per cow that farmers made back in April and May last year, and the equally surprising surge in production per cow that they pulled off over the summer when dairy prices spiked higher.

Has active supply management taken hold?

Are we setting up for a future where milk buyers and cooperative try to actively manage supply to keep it in alignment with demand? There is clear evidence that if enough cooperatives use these programs, it can have a significant impact on production at the national level.

We are in extraordinary times and farmers may be willing to tolerate base/over-base programs or restrictions on milk deliveries now, but will they in a post-pandemic world? I don’t know.

Then you have the “free rider” problem. If nine out of 10 cooperatives tighten their programs to try and bring the market back into balance, but the 10th one doesn’t, the free rider will still get the benefit of reduced national milk production and higher prices without having to irritate their farmers and cut production. But I think it is clear that the industry can cut production, and ramp it up, faster than previously thought when the right incentives are in place.

So, what does the 1.6% production growth mean for the dairy outlook?

It looks bullish to me; it significantly changes the story. The government is buying 2% or more of production, so if we’re looking at milk production growth running 2% or less, the market has some chance of finding balance. That wasn’t likely at 3%-plus production growth. With milk loads still trading at a big discount in the Upper Midwest and Idaho, there is obviously no shortage of milk, and without government purchases the market would still be dramatically oversupplied. But if milk production growth remains restrained and the government purchases play out like we expect in coming months, then there is a possibility we could hit some pockets of tightness and see some upside for cheese and butter prices.