When economists try to forecast markets, they typically look at the history of prices and production and then consider consumer demand and other market factors. Their statistics-based forecasts assume the basic relationships don’t change, and that usually works pretty well.

But the last two years have been the kind that break economic forecasting models. Even if 2021 wasn’t quite a copy of 2020, it wasn’t a return to “normal,” either. Relationships were reshaped across the economy, and they kept right on shifting. So, let’s abandon our forecast models and talk about some of the changes that will drive dairy markets and the whole economy in 2022.

The big, immediate impact of the pandemic on the economy was to change the shape of consumer demand. Live entertainment venues, sports arenas, and restaurants all shut down or moved to remote take-out business for a while. Almost two years later, none of those businesses are back to prepandemic demand. Instead, demand shifted to “stuff,” including more food to eat at home, more things to use at home, and more materials to improve the home.

By changing the shape of what was demanded, consumers left a lot of slack in some businesses and strained others. Manufacturing and transportation have struggled and will continue to struggle through 2022 to catch up to demand. This evolving situation has left crop farmers facing high prices or short supplies of fertilizers and other inputs. These all contribute to high costs on the dairy that will offset projected high milk prices.

Dairy farmers have faced difficulties finding hired help for many years; now the whole economy is in the same boat. During the “Great Resignation” of 2021, millions of people dropped out of the workforce, retired early, extended their search for a more satisfying job, or decided not to work because they didn’t feel safe doing so in the pandemic. This has made it more challenging for employers to find help in all sectors, and also contributes to higher costs for farmers.

The great cheese shift

At the beginning of 2020, the dairy industry knew it was short of block Cheddar cheese processing capacity, and several handlers were building new plants with new lines to address that situation. Then the pandemic lockdown shifted consumer demand from processed food-service cheese (made from barrel Cheddar) to natural cheese (including Cheddar cut from blocks) for comfort at home.

There was plenty of milk, but not enough block cheese. So, the Class III price rose far above other Class prices for most of six months; massive depooling of Class III milk made the negative producer price differentials (PPDs) even bigger; and the federal orders failed in their basic aim of tending to pay a uniform price to all producers in a market.

At the beginning of 2022, several new and existing large cheese plants have added substantially to their cheese block capacity. As a result, for the first time in many years, some analysts expect that butter and powder values will drive the market as a hungry world market demands these products. The average Class IV futures price for 2022 is trading about 90 cents per hundredweight (cwt.) above the average Class III futures price as the year begins.

This could be the new normal if U.S. milk pricing becomes consistently driven by export demand in a world market largely defined by butter and powder values. Exports have taken much of U.S. production growth in recent years, and the U.S. looks increasingly like the country best equipped to supply growing world demand.

The rising cost equation

Finally, inflation is a major concern for farmers and for the entire U.S. economy. November’s Consumer Price Index was up 6.9% from a year ago, the highest price inflation in nearly 40 years. Supply chain issues, including such bottlenecks as overloaded ports and a truck driver shortage, have contributed to inflation by adding costs and slowing down the economy, which might otherwise have absorbed extra dollars in the American economy. Given shortages of labor and raw materials, supply is more generally limited by how fast the economy can grow overall.

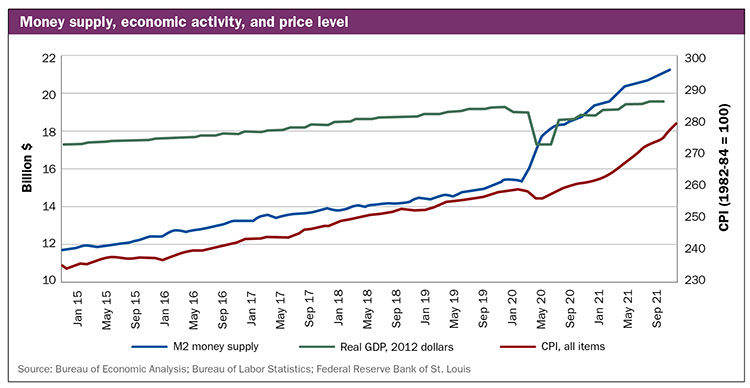

The bigger cause of rising prices, though, is those dollars. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve Bank has been trying to boost the economy by creating a lot of money, essentially loaning money that didn’t exist before and buying bonds with money that didn’t exist before. This has been partly to support heavy (bipartisan) government relief efforts and stimulus spending, and partly to boost growth through easier credit as part of the Federal Reserve’s normal role in managing the economy.

However, this rapid growth in the money supply (a 41% increase since early February 2020) has been unprecedented; too many dollars, with not enough economic growth to absorb them, necessarily leads to inflation. In this case, it has also arguably led to the overheating of the economy, resulting in many of those bottlenecks and supply shortages as an overstimulated demand chases too little capacity to produce.

Borrowing concerns loom

Inflation creates price uncertainty and complicates a lot of economic relationships. If the Fed doesn’t slow the growth in the supply of money and inflation becomes our long-term expectation, it will raise interest rates and complicate borrowing. The history of the 1970s and 1980s will tell us, if we don’t ignore it, that the longer we wait, the more painful it will be when we do control inflation, as it was for so many farmers.

The good news is that the Federal Reserve Bank seems to be taking inflation seriously, signaling a slowdown in their bond purchasing and suggesting potential lending rate increases in 2022. There also is hope that effective infrastructure investments by the private sector and by the federal government as the result of the recently enacted infrastructure law will help grease the wheels of the supply chain over time.

High milk prices won’t look as good as they have in the past, as rising costs and difficulties in processing and marketing continue through the new year. They will sure beat the alternative, though.