Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) was first detected in an Indiana poultry flock in early February, and by early April about half of the states in the U.S. had confirmed cases. This strain of avian influenza is particularly deadly to domesticated poultry, and around 23 million birds have died or been culled to curtail the spread of this devastating disease.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk to human health from the outbreak is low, and no illnesses in people have been reported in North America. That’s the good news. The bad news is that prices for both eggs and poultry products are quickly escalating as this outbreak challenges the poultry industry.

Protecting domestic flocks from wild bird populations and following solid biosecurity measures on poultry farms are two main ways to limit the spread of HPAI. Even though this outbreak does not affect the dairy industry, it is a good reminder that biosecurity is always important in keeping animals healthy and farms safe.

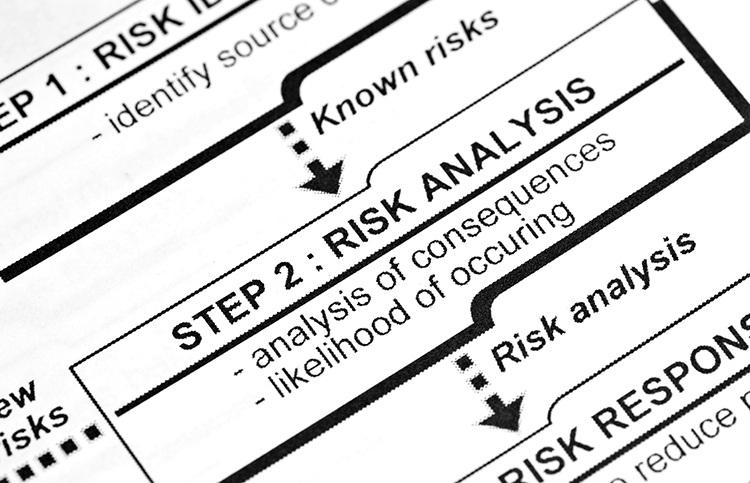

In the April Virginia Cooperative Extension Dairy Pipeline newsletter, extension agent Jeremy Daubert reviewed the three main steps for analyzing biosecurity risk on a dairy farm. He reminded readers that the end goal is to keep everyone safe and healthy.

The first step is a risk assessment. This can be done by a farm owner, safety manager, or a third-party consultant. Daubert advised looking at each part of the farm, from calves to cows. He reminded that vulnerability can be different for certain areas or groups on the farm. For example, newborn calves are more susceptible to disease than bred heifers, he noted.

Also consider visitors; where do they enter and leave the farm? Where can contamination happen?

Daubert’s second step is to develop a risk management plan. This should be based on the risk assessment. The plan should be written down and updated as needed. The steps in the plan should be specific.

To manage risks from humans, he recommended a visitor log to track people who come onto the farm. Camera systems can also monitor visitors and help deter unwanted guests, he shared. In addition, the plan should indicate when and where employees and visitors can wash and sanitize boots.

The plan would also include steps to limit the spread of disease among animals. Preventing wild animals from intermingling with livestock is part of that. Finding ways to separate sick animals from healthy ones is also beneficial.

Communication is the third step of the biosecurity plan. “Communication is key to making the plan a success,” Daubert shared. Everyone on the farm should know what the plan is, how it affects them, and what the goals of the plan are. Biosecurity signs could be placed around the farm and at entrances for visitors to see.

Daubert added that biosecurity policies should also include an emergency action plan and a contingency plan. Contact information for local fire and rescue departments, the herd veterinarian, and poison control are a few of the numbers that ought to be gathered and kept in an accessible location.

“Every farm should make the biosecurity plan specific to their needs and situation,” Daubert concluded. “It should be known by all employees, owners, and visitors. It must also be evaluated regularly and updated as needed,” he added.