The author owns The McCully Group LLC, which provides management consulting for dairy and food companies.

Key drivers of dairy markets have included how corn and feed prices in general evolved through the summer and how Chinese demand might fare. In short, corn prices are well below spring highs, and COVID-19 lockdowns resulted in a significant slowdown in Chinese demand for dairy. These are bearish signals for dairy markets, and next year’s dairy prices are forecast to fall when compared to this year’s levels. On the flip side, high production costs and weak European milk supplies are expected to support prices.

Down pressure on demand

The downturn in dairy prices is due mostly to weaker demand, not higher supplies. U.S. milk production turned positive in June, the first time since last October. However, prospects for milk growth in Europe remain bleak, with some talk of the start of a long-term decline in milk production. The outlook for Oceania is positive for milk supply growth, but weather in coming months will determine the magnitude of the potential gains as New Zealand enters spring.

Looking back to the last time we had strong prices, the sharp decline in prices in late 2014 into 2015 was due to a surge in global milk supplies. That is not expected to happen in 2022 to 2023. The collapse in prices in 2008 to 2009 was due to the global economic crisis. With major economies teetering on recession, this is more of the concern.

While national crop condition ratings from USDA have slipped slightly over the last month, the states that matter in the heart of the Corn Belt have really good crop prospects. Iowa and Illinois, the top two corn-producing states, have corn conditions that are 76% and 74% good to excellent, respectively. Corn prices have dropped from $8-plus per bushel to around $6 for new crop futures. Soybean prices also have dropped from near all-time record highs to under $14 for November futures. This is still high historically, but down significantly from several months ago.

Lower Chinese demand, a reopening of the Odessa port, and a better-than-expected Brazilian corn crop have all been bearish for grain prices. Weather in August is important for crop development, so there is still some risk to the eventual crop size. With favorable weather, there is more downside to grain prices.

What about margins?

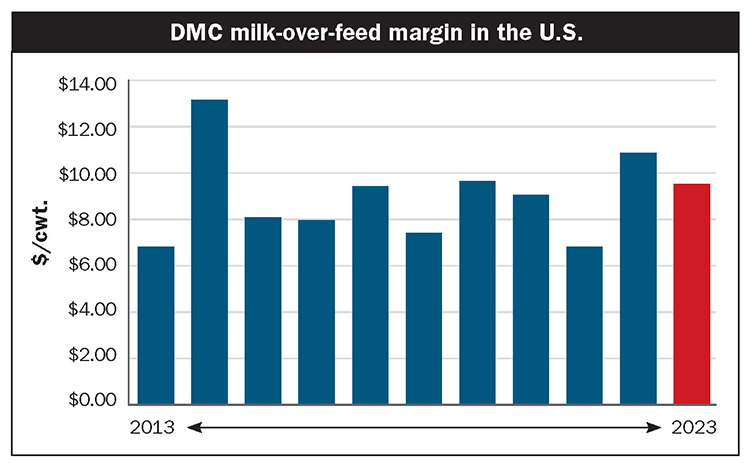

The milk-over-feed margin is falling from second quarter highs, and that trend will likely continue into 2023. Using current futures prices, the projected milk over feed margin using the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) formula is close to $9.50 in 2023, down from $11 in 2022. If realized, the 2023 margin would be about $1 per hundredweight (cwt.) higher than the five and 10-year average. However, all other costs on the farm are also higher and those aren’t accounted for in the DMC calculation. There is also a regional story in feed costs where the West will see higher break-even costs given much higher feed costs than other parts of the country.

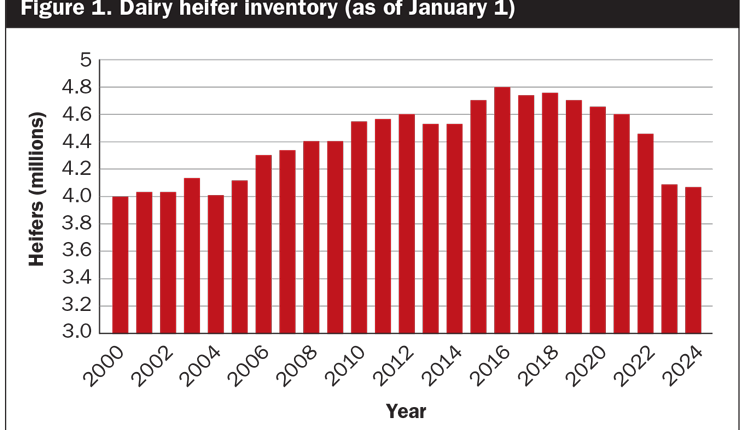

The U.S. dairy herd has been in expansion mode since February, with a gain of 56,000 cows. However, cow numbers remained 78,000 below June 2021, the month when the herd size started to fall from multidecade highs. Cow numbers are expected to exceed the prior year in August although the monthly growth has been uneven. Heifer replacement inventories are low and prices are high.

In some parts of the country, caps on milk growth still limit expansion plans of farms. In fact, cow number growth is concentrated in two states — Texas (+24,000 versus one year ago) and South Dakota (+21,000 versus last year). With expansion expected to continue into 2023, more cows will provide a solid foundation for milk growth.

After seven months of year-over-year declines, U.S. milk production in June grew 0.2% versus last year. Given weak output in the second half of 2021, the percentage increases will grow through the rest of this year and into 2023. With milk per cow up 1% in June, and cow numbers expected to exceed the prior year by August, total milk production is expected to post 1% to 2% growth in the second half of the year and close to average (1.0% to 1.5%) in 2023. High feed costs and tight margins remain a wildcard. The majority of milk growth will likely come from the middle part of the country with minimal to no growth on the East and West Coasts.

Mixed price forecast

The outlook for milk prices is mixed, depending on the region of the country. For now, it appears Class III prices will be below Class IV prices into 2023. If that holds, Class III milk will be pooled and positive PPDs will continue. However, areas with high Class III utilization relative to other classes (Midwest and Idaho) will have a lower price than areas with high Class I or Class IV utilization.

My latest forecast for 2023 has the Class III milk price average just under $18 per cwt. with Class IV slightly over $19. With added premiums and components, the All-Milk price should end up around $20 or higher.

Unfortunately, given high production costs, that will be near break-even levels for many farms and below break-even for high-cost farms. This will provide some support to milk prices as the market will be mindful about herd contraction if prices fall too low. For all of animal agriculture, as long as feed and other input costs stay high, the price of the output — milk, eggs, and meat — will remain well above average.

The downside scenario is a deeper recession than currently imagined with a larger negative impact on demand. Prices aren’t expected to crash like in 2009, but with high costs, even milk at $15 to $17 per cwt. would inflict significant financial pain. The DMC programs should be strongly considered for next year, while farms utilizing Dairy Revenue Protection insurance should lock-in a portion of their milk to protect against further downside. The last three years have presented unique challenges, and a deep recession in 2023 would bring a new set of challenges for everyone.