A complete reversal

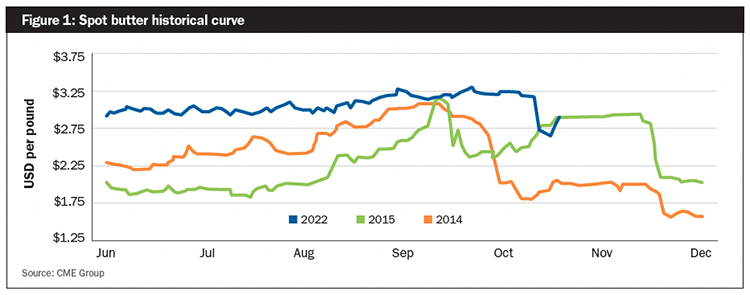

By late summer, the 2022 inventory build reached the lowest point in recent history. As buyers continued to prepare for the forthcoming holiday season, there was a great deal of concern circling around the idea of coming butter shortages. Mainstream media outlets featured stories about the potential of fewer baked goods around the holiday table — perhaps good news for my waistline, but not so good for butter demand. Spot markets were a great barometer of the unease, with CME butter holding north of $2.75 per pound, and eventually, climbing to a new all-time high at $3.2675.

However, the old saying that high prices cure high prices holds true in every market, not just one. Suddenly, U.S. butter and butterfat prices became the most expensive in the world, holding premiums over the Oceania market throughout the summer. That, combined with a strong U.S. dollar, started conversations about butter imports. As U.S. prices moved to a premium when compared to European prices in September, it became clear that the arrival of these offshore inventories was inevitable. At that time, the spread between U.S. and Oceania prices had grown to north of $1.25 per pound. Any capitalist would see that as an opportunity.

Not the first imports

The arrival of these volumes is the one thing that remains in question. Historically, it has not been uncommon to see large influxes of foreign butterfat hit U.S. shores in December. In fact, of all the months in which U.S. anhydrous milkfat (AMF) imports have exceeded 6 million pounds in the last decade, December represented five of the nine months that qualify. This has given rise to a phenomenon of much weaker prices for butter this time of the year. As market participants prepare for an end to the normal seasonal bid that creates highs in late third quarter and early fourth quarter, added pressure from expanded imports only amplifies downside risk.

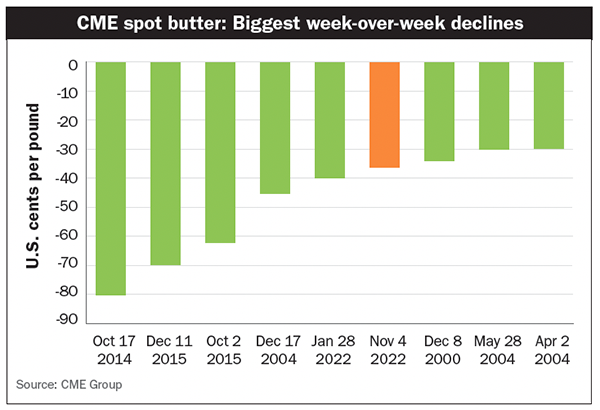

The forward futures curve has been building this scenario into the equation for months. The spread between spot prices and the forward futures curve that spans the winter period had hovered between 20 and 50 cents since September. In recent days, however, this gap contracted quite dramatically, with spot markets doing most of the work. The week of October 31 saw an initial 53-cent drop, with a 16.25-cent recovery as the week came to a close. The spread between spot and December futures narrowed 32 cents over the week to finish at a 20-cent premium. Such a spread still represented the outer band of what the spot price can carry over any current futures month.

The Class IV impact

For dairy producers, the impact of such movement is profound. A single penny move in butter represents just over 4 cents per hundredweight (cwt.) of movement in the Class IV milk price. With butter moving 53 cents lower at one point in that week, one would have expected a more than $2-per-hundredweight drop in Class IV prices.

That did not happen.

Because the market already anticipated spot butter’s fall, at the worst point, December Class IV futures declined by $1.25 per cwt. Following the late-week rebound in butter prices, December Class IV futures actually finished 17 cents higher versus the previous Friday — even with butter down 32 cents for the same period.

Class IV prices have been under some pressure from deteriorating powder markets as well. From the summer peak, announced prices have dropped roughly $3 per cwt. The good news for U.S. powder prices is that they have largely stayed on par with global competitors, namely Europe and Oceania. The sizable gap that still exists between Oceania butter and United States butter (62 cents at the time of this writing) will invite some convergence as we push deeper into the fourth quarter. Though the market has embraced a deterioration of the spot price, such a move would force Class IV prices even lower. Considering the historically high prices still offered in 2023, producers are well advised to manage price risk accordingly.