The United Nations expects India to surpass China as the most populous country on the planet by mid-2023. While it is on pace to be the world’s most populated country, India surpassed China, and all other countries, in milk production long ago. If you include milk production from buffalo, India produces six times as much milk as China and twice as much as the U.S. With that level of production and consumption, a small mismatch in supply and demand could result in significant imports or exports that can affect the world market.

For India, an oversupply of milk during the pandemic has turned into a shortage during 2022 and early 2023. The 2022 monsoon (June to September) was erratic; first it was too dry and then too wet in places, which led to reduced fodder and grain production. The tighter and more expensive feed supplies have been compounded by an outbreak of Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD).

LSD is a viral disease typically spread by biting insects that affects cattle and buffalo. The disease results in a high fever and nodules developing on the skin and mucus membranes that reduce feed intake, milk production, and reproduction. It is hard to get a read on how milk production is doing in real time, but based on anecdotal comments, production growth might have slowed into the 1% to 2% range compared to the 5.4% average growth that India saw from 2014 to 2022.

As we saw in other parts of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic initially reduced dairy demand in India, and consumption took another hit with the Delta wave in April to June of 2021. By July, there was enough surplus hanging over the market that the Gujarat state government announced $20 million in subsidies to help export excess skim milk powder (SMP). The export subsidies and weak milk production in other major exporting countries helped to boost Indian SMP exports in late 2021. As the country moved on from the Delta wave, consumption growth improved and has reportedly been running very strong over the past year despite sharply rising milk and dairy prices in the country.

Between reduced milk production growth, stronger exports in late 2021 and early 2022, and good domestic demand growth, the Indian dairy market is now tight with higher retail prices helping to fuel inflation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) in February was only up 6.1% from last year, but dairy products were up 9.7%. As a result, the government and industry are contemplating importing more dairy products to help bridge the gap until the new monsoon and production season ramp up.

A strong dairy base

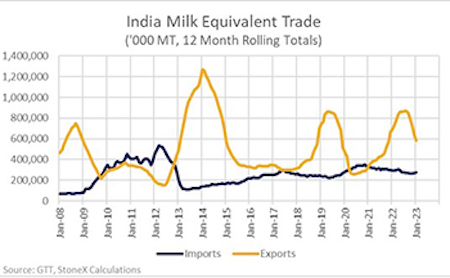

India has historically been a very small importer of dairy products, and since 2013, the country has generally been a net exporter with government subsidies periodically helping to spike exports. Large Western exporters often ogle India like a high value prize sitting inside an arcade claw machine. But no matter how many times exporters try, the prize is always too heavy to actually win.

The Indian government views dairy as an important domestic political priority. An estimated 80 million people in the country are directly involved with milk production and processing. Even in the past when there has been a domestic shortage and the government has allowed imports to come in, dairy farmers protested and blocked dock workers from unloading the product.

Despite the resistance to imports, we have already seen trade flows shifting a little. First, with the domestic supply in India tight, exports are falling. Milk equivalent exports from October through January were running more than 60% below the previous year. We’ve also seen an increase in imports, which were up about 50% year-over-year in December and January. We will likely see exports remain weak, and imports will continue to grow (relative to last year), but even if imports are up 60% for the whole year, India will only absorb an additional 356 million pounds of milk (162,000 metric tons) this year, which would be a 0.2% bump to global import demand. If you factor in their lower exports, they could tighten the world market by 0.4% this year, which could theoretically add 3% to 4% to dairy prices.

India is a massive market with relatively high dairy consumption given their income levels. The population and consumption levels are expected to continue increasing, making their dairy market one of the fastest growing in the world. But India has primarily been a net exporter in recent years and there are large barriers to getting imports into the country. This year might be an exception with imports growing and exports falling, but Indian trade flows are unlikely to have a big impact on dairy prices in the U.S., EU, and Oceania this year.