While Parmigiano-Reggiano has long been made in Italian regions of Parma, Reggio, Emilia, Modena, and Mantua, many people would contend that parmesan itself entered the much larger category of common food names after Italians left their native Italy and carried with them their cheese-making traditions and often their starter cultures.

However, modern-day Italians and the European Union (EU) don’t see it that way.

Officials in both Italy and the EU governance levels want to trademark both Parmigiano-Reggiano and the much larger parmesan category. The EU has begun carrying out that goal as they sign trade agreements with other countries around the world. Once a trade agreement is signed, it becomes the letter of the law. In Singapore, government officials are demanding that all parmesan made outside of Italy carry another name. In a quick scramble to still sell cheese, cheesemakers in New Zealand, the U.S., and the rest of the world are placing stickers over the word “parmesan” and replacing it with “hard cheese.”

While that may be good for Italians who want to sell more cheese, it leaves consumers mighty confused and cheesemakers around the world on the sidelines with the tall task of rebranding the cheese that they long sold as parmesan. I witnessed this situation firsthand on a recent trip to Singapore with the U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC).

Singapore enters the GI battle

The European Union entered into a free trade agreement with Singapore in 2019. Fonterra, a New Zealand Cooperative, brought the matter to court contending that Parmigiano-Reggiano was a geographical indication but parmesan was a common food name. However, Fonterra lost the case ruling earlier this year. That took place when Singapore's High Court ruled “parmesan” is a translation of “Parmigiano-Reggiano” and both were protected by the trade agreement.

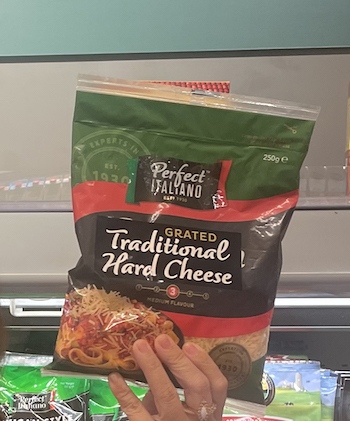

To that end, Singapore is now enforcing the terms and conditions of its agreement with the European Union. While Selina Lum of The Straight Times reported on April 9, 2023, that “there is no immediate impact on traders,” the situation evolved quickly by June. That’s because Singapore government officials are now requiring every cheesemaker outside of the specific part of northern Italy to sell their parmesan as “Traditional Hard Cheese” or another name that does not infringe on the trade agreement between the EU and Singapore.

This broad ruling on the use of parmesan has put cheesemakers from New Zealand, South America, and the U.S. on their heels. It will take a strong rebranding effort to reconnect with customers.

The EU’s take on the matter

“The Consortium estimates that the turnover of fake parmesan outside the EU amounts to 2 billion euros or about 200,000 tons of cheese. That is more than three times the amount of real Parmigiano-Reggiano PDO’s total exports,” wrote Nicola Bertinelli, who is the President of the Consortium in comments published in Italian Food News.

The greater dairy world’s viewpoint

The U.S. and a number of members throughout the world that belong to the Consortium of Common Food Names would disagree with this assessment. There’s so much dissent in the U.S. that Congress is now looking into the matter.

Four U.S. senators and four U.S. representatives have stepped forward to introduce the SAVE Act that would amend the Agriculture Trade Act of 1978. If passed by the 118th Congress, the SAVE Act, as in Safeguarding American Value-Added Exports, would go a long way to protect American food products from unfair trade practices by foreign countries.

The European Union (EU) and its use of geographical indications (GIs) have been the epicenter of these unfair trade practices. With a GI in place, the common food name can no longer be used by any other country governed by a trade deal. As a result, these unfair trade practices block U.S. agricultural products from international markets.

To be certain, this matter will remain a hot button issue for years to come.