Corky, yeasty, oxidized, malty, and scorched might not be words the average person thinks of when describing dairy products, but for food science students who have learned to identify the slightest discrepancy in flavor, texture, or appearance, these terms are second nature. It’s what prepares them for their future careers in food manufacturing and helping make dairy products that consumers keep coming back for.

More than a century ago, the dairy industry’s need for consistency in its products was recognized by the Official Dairy Instructors’ Association, which later became the American Dairy Science Association. At that time, butter was the chief dairy product of commercial interest, and at the same meeting in which members unanimously voted to establish an 80% fat standard for butter, they also voted for the organization of a “butter scoring contest” to teach students the characteristics of desirable products.

First called the “Student’s Butter Judging Contest,” the inaugural event was held in Springfield, Mass., in October 1916 in conjunction with the National Dairy Show. It drew students from nine colleges. The competition has since expanded and connected more students with dairy processing. This month, what is now the Collegiate Dairy Products Evaluation Contest holds its 100th event when students travel to Milwaukee, Wis., for the April 17 contest.

“I think it’s important to be teaching students about tasting dairy products because there are so many uses for dairy no matter what segment of the food industry they’ll go into,” believes Charles White, who has coached teams in this contest at four different universities, including the University of Tennessee currently. He also has a long personal history with the contest, as he, his dad, his daughter, and his grandson all competed.

Constantly evolving

True to its name, students in the first event judged only butter. Cheddar cheese and 2% milk were quickly added to the evaluation panel for the second contest. Like many new ventures do, the 1917 contest faced difficulties garnering funding and was establishing rules and precedent along the way, but it went on thanks to leadership from W. P. B. Lockwood from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and S. C. Thompson and William White from USDA. Still today, the contest’s guidelines indicate that it must be supervised by a USDA official.

In 1926, ice cream evaluation was added to the competition. Until 1929, the contest remained associated with the National Dairy Show, and dairy products judging teams often included one or more students who were also competing in the dairy cattle judging contest to minimize travel expenses. But in 1930, the contest established a new relationship with the Dairy and Food Industries Supply Association and began to hold its event at the annual meeting of either that group, the Milk Industry Foundation, or the International Association of Ice Cream Manufacturers in cities around the country. Participation took off and was never lower than 14 teams between 1927 and nearly the turn of the 21st century. A record-high 33 teams competed in the 1956 contest.

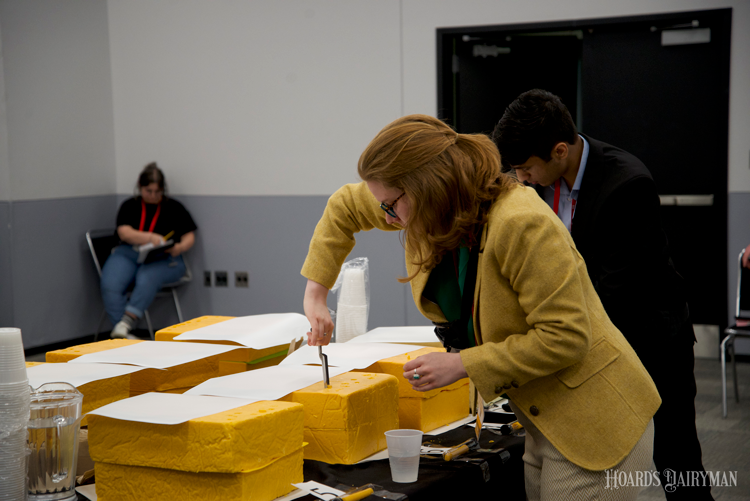

Along the way, cottage cheese was added to the list of products in 1962, and yogurt completed the group in 1977. Today, each of the six products is evaluated and scored on its flavor as students taste samples for defects that could be indicative of problems in the milk or the manufacturing process. The vanilla ice cream, Cheddar cheese, creamed cottage cheese, and blended strawberry yogurt are also evaluated and scored on body/texture characteristics, while the yogurt and cottage cheese are further judged on appearance.

Just like in the early days, industry support remains a critical piece of the competition. Dairy foods companies donate product samples, food industry professionals serve as official judges, and funds are available to help universities travel to the national contest. In recent years, the competition has been held during the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association annual trade show, which allows students the opportunity to learn more about the industry and network with companies in dairy processing.

A contest of the senses

If detecting and evaluating subtle changes in these dairy products sounds difficult, that’s because it can be. Competing students are often enrolled in sensory evaluation courses and may practice all through the school year before the contest in the spring. At those practices, you’d find a wide array of products, brands, and packages for students to sample and discuss. Coaches spend time visiting various grocery stores and even shipping products in from companies outside their area so their students are exposed to as many of the characteristics they may encounter at the contest as possible. A regional contest is often held so students can prepare before the national event.

Because of the subjective nature of sensory evaluation, each product has its own specialized judges. Before the contest, they will gather as a group to review the 20 or so donated samples of their product, choose which eight the students will taste, and decide on the official evaluations. One or two coaches are also invited to consult with the judges the morning of the contest to review the official scores one final time. More opinions are better in a contest like this.

In the same spirit, the coaches gather while their students are competing to discuss the scorecard standards for one of the six products, what to teach students, and how to help them recognize desirable and undesirable qualities. This also helps the contest remain up to date as industry standards change. For example, as dairy processors are using fewer artificial colors, the standard for what is a “typical” color changes.

It’s all done to make sure that students are getting the most useful experience they can. When future food science professionals are trained to know what is desirable and undesirable in these dairy products and think about how to make better products, it makes them stand out to employers manufacturing those items.

That’s what happened for Vanessa Teter, a former food science student who earned a job in dairy product development 14 years ago and today works with the Horizon Organic brands largely because she had judged dairy products. “I had no dairy experience other than I competed in this contest,” she explained. Today, she also gives back to the contest by chairing the publicity committee and getting more students interested.

It takes practice to develop the keen eye and sense of taste necessary to be an effective dairy products judge, but there are certainly worse ways to spend time than sampling milk, butter, cheese, yogurt, ice cream, and cottage cheese. Students have been doing it for 100 years to strengthen the dairy community, and the next 100 look just as bright.